Should Students Learn About Black Lives Matter in School?

The lengthy timelines of publishing new history textbooks—and the problematic narratives those books often present—push primary resources to the forefront of current-events education.

If the Chicago social-studies teacher Gregory Michie waits for a textbook to teach his students about the Black Lives Matter movement, the first seventh-graders to hear the lesson won’t be born for another seven years.

Despite the historical implications of that movement, bureaucratic timelines all but quash any possibility that students might learn about today’s events from an actual history textbook in the near future. According to Anthony Pellegrino, an assistant professor of education at the University of Tennessee-Knoxville, many school districts receive new books on a seven-year cycle. However, in some states, schools don’t receive new books for 10 to 12 years, and the most current material in those books could be a few years old. Certainly digital textbooks shorten this timeframe, but physical copies lag far behind: In some districts like Michie’s, students are reading textbooks that don’t even contain the name Barack Obama.

On top of that, the chapters on America’s most recent history often fall short. Because content on, say, the American Revolution, has been read and edited over the course of multiple book editions, more recent chapters often “feel like just add-ons.” Pellegrino said. “They're so afraid to tackle anything current because we don't have the perspective of history to be able to inform us more. As such, the sentences, the words, the paragraphs, are just really vapid.”

But Michie, who teaches seventh- and eighth-graders at The Windy City’s William H. Seward Communication Arts Academy, doesn’t let outdated textbooks deter him from addressing timely, sensitive topics in the classroom. Michie said the social-studies textbooks at Seward are around 20 years old, but even if they were contemporary, he wouldn’t rely on them. The history books “are just horrible,” he said. “They dodge controversy. Textbooks are commercials for the countries they're made in.” Instead, Michie’s conversations with students are rooted in sources ranging from images to political cartoons as he moves social-justice issues to the forefront with lessons that draw on modern cases like those of Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, and Michael Brown.

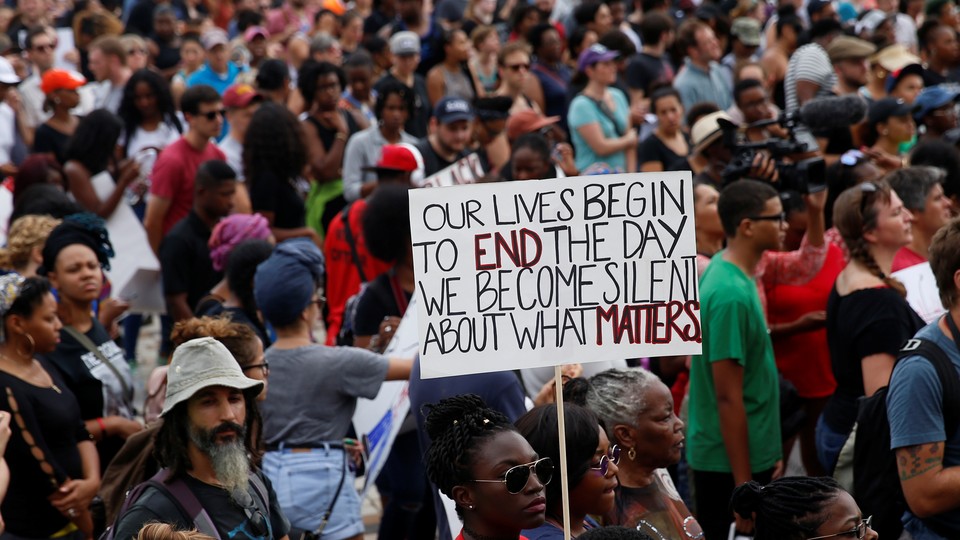

The use of primary-source documents has become a popular tool for teachers seeking to bring current events into the classroom, particularly as schools have adopted the Common Core standards, which encourage students to engage with such resources. But the immediacy and timeliness of police brutality, activism, and institutionalized racism have led educators to consider the ramifications of sharing these issues with students. Michie said talking about newsworthy events is critical, but his teaching of sensitive contemporary issues has drawn criticism—someone on Twitter called the lessons indoctrination. However, he thinks the world outside the classroom is too relevant to ignore inside school walls. Not discussing current events and issues of race, Michie said, sends a stark message to kids because “our silence as teachers speaks very loudly to our students."

In addition to the relevance of topics like Black Lives Matter, Daisy Martin, a senior research associate in the Graduate School of Education at Stanford University, said weaving current events into lesson plans provides an opportunity for history teachers to re-engage their students. "One of the most common words that’s used to describe history in K-12 is 'boring,' and kids think of it as, ‘It's all done, and it's sort of determined,’” Martin said. By talking about what is going on now and explaining the connections between past and present, teachers can work to remove that stigma.

However, as Michie demonstrated, teachers who choose to bring current events into the classroom face numerous challenges. And it’s not just claims of imprinting a teacher’s opinions on the class—Martin said some history teachers struggle to discuss sensitive topics because they may feel like they don’t know enough about the topic, have too much to cover already, or lack the school-wide support needed for such conversations. Michie, though, is adamant about not shying away from sensitive topics: “Public-school teachers should stand up against racism, should stand up against homophobia, should stand up against religious intolerance. To me, that's not [taking] a side. We have to advocate for, and believe in, and have high hopes for all of our students.”

Not everyone agrees with Michie, and textbook publishers are saddled with the task of appealing to a wide audience around the country. And yet, certainly today’s political, social, and economic climates will be written about in history books. The events of today have been compared to the tumult of 1968, a year frequently cited as one of the most dynamic in American history—that year, both Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy were assassinated, riots burst out during the Chicago-hosted Democratic National Convention, and the Tet Offensive was launched in Vietnam.

In contextualizing the Black Lives Matter movement for students, however, the historian Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, the author of From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation and a professor at Princeton University, said these comparisons often strip current events of their unique nuances: “Because the 1960s were the last big period of protracted or prolonged struggle in the United States, there is a tendency to use that as the touchstone for every type of protest that breaks out,” Taylor said. “It's important to get the framing correct, because it's important to distinguish between different political situations and different historical periods."

The impulse to make these comparisons only increases the necessity for educators to have access to quality teaching materials. Still, a lack of updated physical textbooks may not be such a bad thing for students. Taylor said textbooks are often host to the biases of the people who write and approve them, and Martin said these resources are often, “silent about controversy ... Even though it’s the lifeblood of a democracy, and history and social studies is one of the ways that we learn how to manage and understand controversy and make our own decisions about what's best."

Martin said that a textbook provides just one perspective and should be “moved off its pedestal.” And physical copies of textbooks are far from the only way educators can weave current events into lesson plans. For teachers seeking to bring current-events lessons to the classroom, not only are there primary sources covering the Black Lives Matter movement readily available, but the inclusion of these documents also aligns closely with Common Core standards. Multiple textbook publishers declined to be interviewed for this story.

Carmen Fariña, the chancellor of New York City Schools, told my colleague in a conversation last summer that the aim of the Common Core “screams social studies.” She emphasized the need for students to have a constructive way to discuss current events in the classroom using primary sources. “No one reads a textbook as an adult,” Fariña said. “What do you read? You read the newspapers, you read magazines, and [social studies is] basically based on news.”

Jinnie Spiegler, the director of curriculum for the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), has made lesson plans available on topics including the development of the Black Lives Matter movement, the protests in Ferguson, Missouri, and the death of Freddie Gray. These materials go through a different vetting process than textbook chapters, and Spiegler said the ADL is a civil rights organization but does try to present multiple points of view. The plans rely on primary sources, and Spiegler said the ADL usually publishes the lesson plans within a few days of an event—a dramatically shorter timeline than that of publishing a new edition of a textbook.

This timeliness especially matters when reaching a generation that is constantly plugged in. “They're reading it in their social media platforms, they're reading it on Facebook and Instagram and they're seeing what's happening,” Spiegler said. “But they’re not having the opportunity to really talk about it, to read about it, to learn what actually happened and think critically about it."

And these conversations do have an impact on students, Michie said.

Following Michael Brown’s death and the protests in Ferguson, Missouri, Michie said his students were sharing their analyses of political cartoons. One student, who was at times difficult to engage, wouldn’t stop asserting himself and presenting his own ideas. After a few minutes, Michie, who admitted this goes against his philosophy as a teacher, told the student to sit down or he would fail the assignment. The student’s response has stayed with Michie ever since: “What he said back to me was, ‘Mr. Michie, I don't care about the points. I just want to participate.’"