The story of law enforcement in the Oregon standoff is one of patience.

On the most obvious level, that was reflected in the 41 days that armed militia members occupied the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge near Burns. It took 25 days before the FBI and state police moved to arrest several leaders of the occupation and to barricade the refuge. It took another 15 days before the last of the final occupiers walked out, Thursday morning Oregon time.

Each of those cases involved patience as well: Officers massed on Highway 395 didn’t shoot LaVoy Finicum when he tried to ram past a barricade, nearly striking an FBI agent, though when he reached for a gun in his pocket they finally fired. Meanwhile, despite increasingly hysterical behavior from David Fry, the final occupier, officers waited him out until he emerged peacefully.

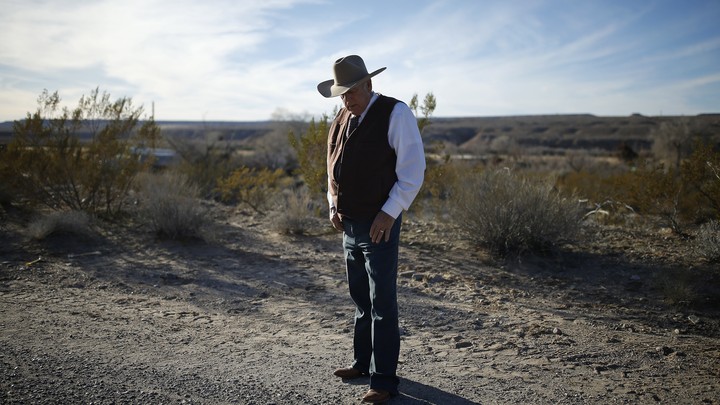

But all of these pale in comparison with the time it took to apprehend Cliven Bundy. The father of Ammon and Ryan Bundy, two leaders of the Oregon occupation, he was arrested Wednesday night at the Portland airport when he arrived from Nevada. He had flown in to support the remaining group of four, three of whom surrendered shortly after he was taken into custody. For the FBI, the wait to arrest Bundy was longer: almost two years, since Bureau of Land Management agents who tried to remove his cattle from federal land where they were grazing without permits or fees were met by a huge group of armed men who turned them away.

Or perhaps the wait was much longer. As the criminal complaint against him notes, he had illegally grazed his cattle on federal land for more than 20 years, and he’d been under a federal court order to remove his cattle since 1998—an order he’d brazenly flouted.

The FBI hasn’t said much about why they arrested Bundy when they did. During a press conference Thursday, Greg Bretzing, the head of the FBI’s Portland office, referred questions to the district of Nevada. A call to the U.S. Attorney’s Office was not returned. Perhaps the government felt it would be easier to arrest Bundy away from home and away from less likely to be around armed men. The complaint describes the situation for agents in the 2014 standoff—outnumbered, surrounded, outgunned, and afraid for their lives:

Cliven Bundy has been charged with a long slate of offenses, including conspiracy to commit an offense against the United States; assault on a federal law-enforcement officer; use and carry of a firearm in relation to a crime of violence; obstruction of justice; interference with commerce by extortion; and aiding and abetting. The full document is here. Those charges together bring a hefty set of penalties, and Bundy, 74, could spend the rest of his life in prison if convicted of several of them.

Those charged in the Malheur standoff have all been charged with conspiracy to impede officers of the United States from discharging their official duties through the use of force, intimidation, or threats. That’s a federal felony that carries as many as six years in prison. The virtue of the charge from prosecutors’ perspective is that they have recordings of the occupiers discussing their deeds, which were broadcast live. That makes it comparatively easy to prove they conspired without having to prove they actually followed through.

During a press conference Thursday, however, Bretzing suggested there would be more charges to come for some of the occupiers. Once again, patience is the watchword: He described a painstaking process to go over the refuge in the coming days and weeks, and while he said the FBI would try to turn it over to the Fish and Wildlife Service to reopen as quickly as possible, there were several steps required to get there. First, law enforcement was sweeping the entire refuge to make sure no one else was left. Then a multi-agency bomb squad will go over the property. (Asked whether that was in response to any specific threat, Bretzing said only, “Several things that have happened over the last 41 days that have led us to believe this a prudent thing to do.”) After that, an FBI evidence team will go over the center, followed by a forensic team examining computers, and finally an FBI art-crime team that will assess Paiute Indian burial sites and artifacts that may have been disturbed.

Just how willing were police to wait? Going back to the January 26 arrests and barricading of the refuge, it’s notable that the FBI only decided to act as Oregon authorities got increasingly anxious. Residents of Harney County were angry, restive, and afraid. Governor Kate Brown had written to Attorney General Loretta Lynch and FBI Director James Comey asking for action.

“I would say the armed occupiers have been given ample opportunity to leave the refuge peacefully,” Bretzing said at the time. “They have been given opportunities to negotiate. As outsiders to Oregon, they have been given the opportunity to return to their families and work through the normal legal process to air grievances. They have chosen to threaten and intimidate the America they profess to love.”

Even then, it turned out the FBI was willing to wait another two weeks for the remaining holdouts to give up. Bretzing didn’t offer much detail about why they decided to bring the siege to an end now, except that one occupier’s ATV journey outside the perimeter the militia had set up seemed to spur the action. “We felt it was time, both for safety of those on the refuge and for the safety of the officers in the event,” he said. When they moved, they did so in concert with people like Nevada legislator Michele Fiore and the Reverend Franklin Graham, folks whose views on the occupiers’ cause Bretzing rejected Thursday, but who were able to de-escalate the situation.

The risks and rewards of the FBI’s strategy remain up for debate. Federal authorities seemed to approach the situation with the goal of not replicating the catastrophes at Waco and Ruby Ridge, where overwhelming force led to many deaths and serious backlash against the federal government. In this case, where the occupiers were specifically alleging an overweening federal government, such a response would have validated that view for many critics. Yet other critics have complained that the hands-off response only emboldened the occupiers. There are calls for thousands more armed “Patriots” to descend on Burns. And after all, it seemed like Cliven Bundy had gotten away with his rebellion in Nevada.

But it turned out the feds hadn’t given up on nabbing Bundy—they were just waiting patiently for the right moment. Whatever the perverse incentives risked by the wait-’em-out approach, it’s hard not to look at the result in Oregon and be impressed: Every occupier gone, the leaders apprehended and in jail, and only one violent death—and that of a man who had declared his intention to die before being arrested, was reaching for a pocket with a gun, and, according to the testimony of another occupier, crying, “Shoot me!” The difference between the FBI’s hesitation and the hasty resort to force by local police departments in dozens of high-profile shootings over the last year couldn’t be clearer, and might provide a model for how more cops should operate.

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.