Around Towns: Rock Hill

Just over the state line is a place where bicycles will buzz by you, discs will fly above you, and the markets will feed you. But if you look more closely at Rock Hill’s past, you’ll also find textile mills that once grew the place, the story of the man who invented the Rice Krispies characters, and one of the most compelling acts of courage from the civil rights movement

DOWNTOWN IS full of orange cones and construction barriers. One sign advertises 40 new apartments off ering “distinctive urban living.” Down the block, men in their 30s with various stages of beard spill out of the new bottle shop that sells craft brews and specialty wines. Up the street, a few older men grumble about the spandex-clad couple pedaling by on their bicycles. Around the corner, Old Town Farmers Market fills the small parking lot behind Provisions Local Market, a store advertising organic produce, raw milk, and “pastured meats.” Spread across folding tables are fresh okra and peaches, handcrafted soy candles, and homemade pork skins—this is still South Carolina, after all.

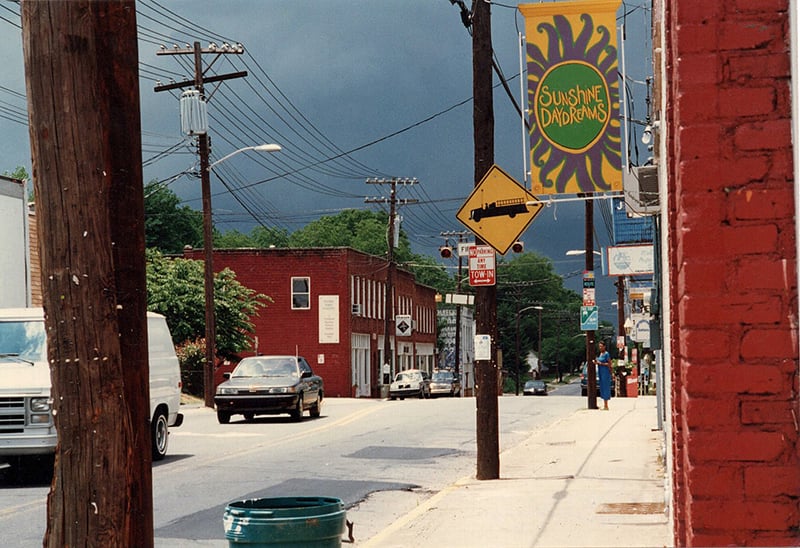

Just a few years ago, it would have been hard to imagine this type of activity on a weekday evening in Rock Hill. Like many downtowns, Rock Hill bled businesses and residents through the 1970s and 1980s as retailers sought space in the new malls near interstate exits. In the late 1970s, some folks in Rock Hill had a big idea to stop the exodus: The city would bring the mall downtown. So they slapped a roof over two blocks of Main Street and called it the TownCenter Mall.

The novelty didn’t last, and by the early 1990s the mall sat mostly deserted. Folks started a fundraising campaign to restore Main Street. They called it “Raze the Roof.” When they had the money, they tore up the roof to reveal well-preserved historic buildings, then rebuilt the streets and sidewalks. Still, it would take years for those sidewalks to get much use.

When Brendan Kuhlkin opened McHale’s Irish Pub in one of the old buildings that had been part of the mall in 2004, a few people questioned the choice.

“After 6 p.m., McHale’s was literally the only light on Main Street,” Kuhlkin says.

Since then, though, things have steadily grown. The markets. The folding chairs. The men with the beards. The pork skins and soy candles and distinctive urban living.

“Some people think we just turned on a light switch,” Kuhlkin says. “It’s like the musician who everyone thinks is an overnight success. He’s says, ‘Wait a minute, guys, I’ve been working at this for 20 years.’ ”

The Main St. Bottle Shop serves up beer and wine in a town that’s quickly growing up. More than 130 apartments have sold in the Riverwalk area and plans for several hundred more are in place for the next decade.

Across town, techno music blares over the whir of bicycle spokes. The riders make loops around the track—blurs of brightly colored spandex suspended sideways on the 42-degree embankments. The bikes have no gears and no brakes, but ever since the Giordana Velodrome opened here on the northern edge of Rock Hill in 2012, people have been coming from as far as Pennsylvania just to take a spin.

The Giordana is one of over two dozen or so velodromes in the United States. If you don’t know what a velodrome is, think about a miniaturized NASCAR track with banked curves—or, better yet, just drive down and see it yourself. The Giordana has already hosted national races and put Rock Hill on the map of this tight-knit community of velodrome riders.

The velodrome isn’t the only sports venue in town. There are the soccer fields that draw thousands for traveling team tournaments at Manchester Meadows, and there are baseball fields that draw the same types of crowds to Cherry Park. The disc golf course tucked beside the Winthrop Lake hosts the United States Professional Disc Golf Championship—yes, that exists—every October. The city has invested millions over the last few decades building these fields and courses in hopes of attracting sports tourism dollars. It’s worked. The city estimates that sports tourism now brings between $15 million and $20 million every year to Rock Hill.

Rock Hill is a difficult town to describe. It’s never been a river town, but you can now spend hours strolling along the new greenway on the banks of the Catawba and watch kayakers bob and weave around the rocks where herons perch. Rock Hill’s not exactly a college town, either, though the 6,000 Winthrop students make their presence known—jogging under the canopy of Oakland Avenue, laughing in groups at McHale’s pub, or staring at their laptops and textbooks in the upstairs loft of the new Amelie’s branch in a renovated bank building on Main Street.

North of the velodrome, a network of new streets sits dusty with construction debris, lined by new two-story houses with bright paint and stone trim. To the south, faint wisps of smoke rising from some of the few remaining industrial plants along Celriver Road serve as a reminder of Rock Hill’s past.

For nearly 60 years after the end of World War II, the 1,000-acre Celanese textile plant produced acetate filament that wound up in everything from curtains to cigarette filters. When the plant closed 10 years ago, some workers blamed it for their health problems, while others kept bricks from the demolished mill as souvenirs.

Top: The Flipside Restaurant, owned by Jon and Amy Fortes, opened earlier this year and serves up dishes such as salmon with corn purée, blistered tomatoes, and red peppers. Bottom: Provisions sells organic produce, raw milk, and “pastured meats.”

The shuttered Celanese plant might have become another open wound in the textile town’s landscape, which had seen mill after mill close through the 1980s and 1990s. The site was dirty, with years of accumulated industrial waste. But a group of developers who specialized in rehabbing contaminated properties stepped in. They proposed a massive complex of shops, offices, and homes on the surprisingly scenic riverfront. And although the timing of the Riverwalk development’s groundbreaking at the depth of the housing market crash couldn’t have been worse, more than 130 homes and apartments have sold so far, and plans are in place to build several hundred more over the next decade.

Rock Hill has a long history of innovation. Take, for instance, John Gary Anderson. He was a buggy maker who started building cars in the early 1910s. The Anderson Automobiles, made in a Rock Hill factory, competed with Detroit’s high-end models through the Great Depression.

There’s also Vernon Grant, who drew advertising illustrations from his family’s cattle farm just outside of town. His work graced magazine covers and cereal boxes throughout the 20th century—Rice Krispies fans will recognize his characters Snap, Crackle, and Pop.

***

THERE ARE innovations born of optimism and innovations born of outrage. A combination of the two drove nine students at Friendship Junior College in 1961. They’d read about and watched other black students around the South demand their rights to be served at segregated lunch counters. Rock Hill was no different; the lunch counters and Woolworth’s and McCrory’s department stores downtown allowed black customers to buy food but not to sit at the counters.

If you want a little electronic noise, Joe’s Video Games has plenty of vintage games.

On the morning of January 31, 1961, the students left the college’s campus on the west side of town and headed for downtown. They marched past the mill village and the offices of the Evening Herald, singing hymns and songs as they went. A crowd of police officers and sheriff’s deputies lined Main Street, waiting for them. Somehow, they had heard about the student’s plans.

The nine marched on, past the crowd of white townspeople now gathering to watch them and hurl taunts and slurs. Then, at about 11:30 a.m., they opened the door to McCrory’s and walked up to the counter, with police officers silently following. They placed simple orders—hamburgers, Cokes, and coffee. Within seconds, officers dragged them out and into waiting station wagons behind the store.

“Before my bottom touched the seat,” Clarence Graham remembered in a 2015 interview with NPR, “they had me on the floor.”

Lunch counter sit-ins had become almost routine by then. Usually, the protesters would be arrested and post bail. The story would be in the papers for a day or two until people lost interest. All that bail money wasn’t cheap.

“We were losing money,” Friendship Nine member Willie McLeod said in a recent documentary. “The NAACP and the other organizations were losing money.”

The Friendship sit-in would change that. After the students were booked in the York County jail and charged with trespassing, they stayed. They didn’t post bail, and intentionally set about to serve whatever sentence the judge handed down. That’s how the nine students wound up at the York County prison farm, cutting brush and moving bricks and concrete blocks from one end of the yard to another. Their sentence was 30 days, and they served every minute. Their story spread throughout the country and attracted hundreds of supporters. From there, the “Jail, No Bail,” strategy spread to sit-ins throughout the South.

The nine students carried their trespassing convictions with them for most of the rest of their lives. But they “never felt guilty of anything,” Clarence Graham remembered.

Finally, in January 2015, a judge overturned the charges for the eight surviving members of the group.

***

MCCRORY'S IS long gone today. The old building has been through a few tenants since then. Today, the Five & Dine restaurant serves customers. A replica of the lunch counter remains, the names of the Friendship Nine etched into the seats’ metal backs.

If you want a little quiet time, talk a stroll in the Riverwalk area of town.

It’s hard to imagine the counter as a scene of conflict on this Thursday evening in July. Two old friends catch up over burgers while a few seats down a father buys his daughter a milkshake.

Mayor Doug Echols looks at downtown now and sees years of work coming to life in the farmers’ markets and bottle shops and yoga studios.

More recently, the mayor’s attention has been with the area to the west of Main Street, where the shell of what was Rock Hill Printing and Finishing Company sits. Like the Celanese plant out by the river, “The Bleachery” as RHPF was known, employed thousands of locals on a massive downtown site before it closed in 1998. Some hope this area can be an employment center again—only this time as a “knowledge park” full of companies providing modern technology in restored century-old buildings. It’s already starting to happen downtown, where new technology companies such as SPAN Enterprises and RevenFlo have gone from start-ups to headquarters. Other, smaller companies crowd the Technology Incubator, also on Main Street.

On the opposite end of the street, though, no one is thinking about technology. Couples walk dogs and families picnic in the grass or gaze at one of Rock Hill’s newest attractions, a lighted fountain with alternating patterns. Fountain Park is an attraction of its own now—one that doesn’t require a technology degree, or a bicycle, or passion for organic food. And you’d never know that less than two years ago, it was just a parking lot with cracked asphalt.

Chuck McShane is a writer in Charlotte and director of research at the Charlotte Chamber. He is the author of the 2014 book A History of Lake Norman: Fish Camps to Ferraris. Reach him at chuckmcshane@gmail.com or on Twitter: @chuckmcshane.

THE DAY TRIP

Eat

Millstone Pizza

This spot has 40 craft beers on tap, woodroasted pizza, and it’s open until midnight most nights. Try the Della Posta.

121 Caldwell St., Ste. 103, 803-980-2337

The Flipside Restaurant

This “Southern eclectic” restaurant was opened earlier this year by Jon and Amy Fortes, who also own the popular Flipside Café in Fort Mill. This spot has quickly become known for its shrimp and grits and has outdoor dining available on its brick patio/alleyway.

129 Caldwell St., 803-324- 3547

Michael’s Rock Hill Grille

On tree-lined Charlotte Avenue just a stone’s throw away from Winthrop University, Michael’s Caribbean-themed café is a Rock Hill classic.

1039 Charlotte Ave., 803-985- 3663

Shop

Joe’s Video Games

In the market for an Atari 2600? Want to add a Mike Tyson’s Punch Out! arcade console to your living room? Joe’s Video Games in downtown Rock Hill is the place to go.

139 Caldwell St., 704-507-6170

Overhead Station

A Main Street mainstay since 1977, Overhead Station offers custom stationery and unique gifts.

212 E. Main St., 803-327-6332

Do

Glencairn Garden

The 11-acre garden near downtown includes waterfall fountains, shaded trails, and a variety of year-round blooming plants. Free admission. Open daily, dawn until dusk.

725 Crest St., 803-329-5620

Giordana Velodrome and the Novant Health BMX Supercross Track

Check out the Friday night race series at the Velodrome and the nearby BMX Supercross Track. Bicycle rentals are available at the velodrome but a $20 certification course is required.

Riverwalk Pkwy.

Catawba Indian Nation Cultural Center

Just east of Rock Hill, the only federally recognized Native American tribe in South Carolina maintains its reservation. The festival Yap Ye Iswa, or Day of the Catawba, is held the Saturday after Thanksgiving. The reservation also includes more than two miles of nature trails.

1536 Tom Steven Rd., 803-328-2427

Fountain Park

Downtown Rock Hill’s newest addition, Fountain Park replaced what city officials say was “the ugliest parking lot in Rock Hill.” Take a stroll around the field, hear a band play on the outdoor performance stage, or just watch the lighted fountain and its half-dozen patterns.

E. Main St.

This article appears in the November 2015 issue of Charlotte Magazine

Did you like what you read here? Subscribe to Charlotte Magazine »

|

Chuck McShaneEmail him at chuckmcshane@gmail.com or reach him on Twitter: @chuckmcshane. Also by Chuck McShane:→The Story of Charlotte |