On Wednesday, California said goodbye to its mandatory statewide water restrictions for urban use, a tip of the umbrella to the relatively wet winter northern parts of the state had, which helped fill reservoirs and brought a relatively normal snowpack to the Sierras.

That decision was probably premature. For Southern California especially, the drought is still just as bad as ever. In much of the Sierra Nevada and Southern California, there’s still two or three entire years of rain missing since this drought began five years ago.

If that’s not a reason to continue with large-scale water conservation, I don’t know what is. In making the announcement, the state declared that local communities could set their own limits, so the opposite will likely happen as they back off on restrictions for things like watering lawns.

Add climate change on top, and California is still heading toward drought disaster. A warming spring season means the state’s crucial snowpack now melts much faster than in the past, creating a false sense of security before running out entirely. So although this year’s snowpack was near normal on April 1, six weeks later it’s already down to just 35 percent of normal for late May. In a few more weeks—at this rate—it’ll be gone entirely.

Basically, it was an “El Niño in the streets, La Niña in the sheets” kind of winter for the entire West Coast. Seattle wound up with its rainiest rainy season on record, something unheard of for an El Niño year, which typically dries out the Pacific Northwest. And then in some parts of Southern California, the drought’s severity actually ticked upward slightly since the start of the rainy season—and that’s what we’d expect with a typical La Niña pattern, not El Niño. (We are currently in the transitional period between these two weather events.)

The quick reason for the weirdness of the just-completed winter is that the jet stream, which typically delivers the relentless coastal storms to California that make El Niño famous, was much farther north than expected. (My winter outlook for the West Coast, for one, was pretty off-base.) But why? Smarter meteorologists than me are digging into that answer.

Anthony Masiello is a New Jersey–based meteorologist who focuses on seasonal predictability and has provided convincing evidence that the character of El Niño itself might be changing as the planet warms. Here’s the theory: Since warm air expands, the volume of our entire atmosphere is growing, and the circulation system of the tropics is expanding toward the poles. That could be shifting the jet stream northward, too, at least during El Niño years.

Since the last strong El Niño in 1997–98, we’ve had nearly two decades of global warming. But that warming hasn’t been uniform over the entire planet, so to truly understand how this might affect El Niño, one has to specifically consider what has happened in the Pacific Ocean, as Daniel Swain points out, and that’s a very complex thing to sort out. Chances are, though, that global warming is shifting El Niño precipitation patterns geographically at least a little. For Southern California, that might have been enough to cut off the tap almost entirely this year.

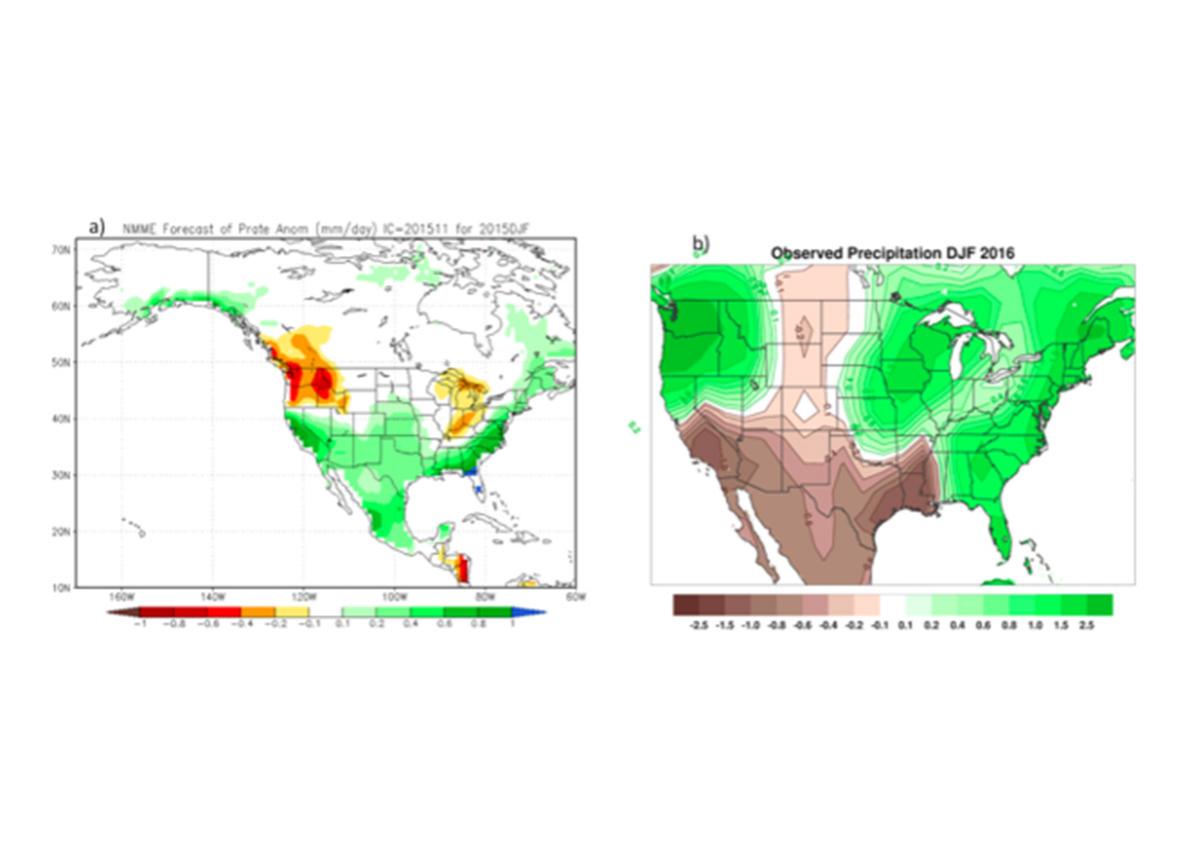

Judah Cohen/Atmospheric and Environmental Research

The meteorologist who’s looked at this in the most detail is probably Judah Cohen. Last month, he posted a “special recap,” which contains a torrent of meteorological detail, of just why most West Coast forecasts were so wrong. He also published a correspondence in the journal Nature on May 11 about the same topic. In a phone conversation, he cut to the chase: “The models clearly failed. … It was a good year for chaos.”

This winter’s chaos has caused Cohen to lose a bit of confidence in using past El Niño patterns to predict future El Niño patterns, he says. Even though this El Niño was one of the strongest on record, “impacts-wise, this winter was classical La Niña.” Cohen thinks he’s found a big reason why: This winter featured sharply fluctuating strength of the polar vortex, which in its strong phase tends to pull the Pacific jet stream northward. That, combined with the steady pressure of a gradually warming tropics, might have done the trick.

Whatever the reason for the weird El Niño on the West Coast, the result is Southern California remains locked into its worst drought on record. Going into the state’s six-month dry season, for the near-term at least, fire conditions there are only going to get worse.

The drought has already had widespread ramifications. By the U.S. Forest Service’s count, 40 million trees statewide have died during the five-year drought, 29 million in just 2015. Dead trees are like matchsticks for forest fires—Daniel Berlant, a spokesman for California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, told the San Francisco Chronicle that fire danger has markedly increased as a result. “No level of rain is going to bring the dead trees back,” Berlant said. “We’re talking trees that are decades-old that are now dead. Those larger trees are going to burn a lot hotter and a lot faster. We’re talking huge trees in mass quantity surrounding homes.”

Not only that, but this year’s rains, where they did fall, may have actually increased fire danger by spurring a good crop of grasses and shrubs, so-called “ladder fuels” that help fires jump from smoldering near the ground to hopping from treetop to treetop.

In a briefing this week, U.S. Forest Service Chief Tom Tidwell said that California’s trees will continue to die due to drought for at least three more years, and this year’s switch to La Niña probably won’t help. I know, I know, calling for a La Niña–caused dry rainy season next year is a little awkward considering this past year’s forecast performed so horribly. But the long-term trends show that should the warmth of the recent past continue, California will continue to have less snowpack for a long time to come. “This is not weather,” Tidwell said. “This is climate change. That’s what we’re dealing with.”

Last year’s fire season was the worst on record nationwide, with 10.1 million acres burned. Federal and state governments have upped their firefighting budgets for this year, expecting another very bad fire season. In California, Cal Fire has awarded millions of dollars in grants to communities in part to assist with clearing dead trees from around houses.

Wildfire photographer Stuart Palley, whose work has been featured on Slate, spent the winter in firefighting training and will embed with a fire crew in the Cleveland National Forest near San Diego later this year as a crew member—made possible by that increase in funding.

“[The firefighters’] view is, ‘anything can happen at anytime, anywhere. It’s a new normal. Fire season is year-round,’ ” Palley said. “They’re all staffed and ready to go right now.”

Palley, like many of us, was caught off-guard by the size and intensity of the fires in Alberta, Canada, already in May. While Southern California has a much different ecosystem than the northern boreal forest, if anything, there’s a much greater risk of wildfires becoming urban fires simply because of the sheer number of people living near forests and the severity of the ongoing drought.

“I think this might be Southern California’s year,” Palley said. “I think a lot of firefighters around here are wondering it’s not a matter of if it’s going to happen, but when it’s going to happen.”