In 2012 protests erupted in Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina over the demolition of a much beloved local park to build a business complex. A movement under the slogan “This Park is Ours” aimed originally at protecting the green space soon broadened into a collective movement aimed against corruption, lack of transparency, economic inequality and dwindling social services. Hundreds of protesters from all social classes and religions gathered daily in the endangered park, becoming part of a Bosnian spring that came to represent a struggle for human dignity and accountability under most articulated civic movement since the 1992-1995 war.

From Banja Luka to Gezi Park, Turkey to Rosia Montana, Romania to the land wars across India, social conflicts are increasingly playing out through battles around environmental resources and in defence of common land.

These struggles have sometimes toppled governments, such as the coup in Madagascar in 2008 that brought “land-grabbing” to global attention when Daewoo was given a lease to grow food and biofuels for export on half the country’s land. But most of the time, the evictions, forced relocations and the violent repression of those impacted by contamination from gold mines, oil extraction, plantations and agribusiness operations are rarely covered in the press. Ecological violence inflicted upon the poor is often not news but simply considered to be part of the costs of “business as usual”.

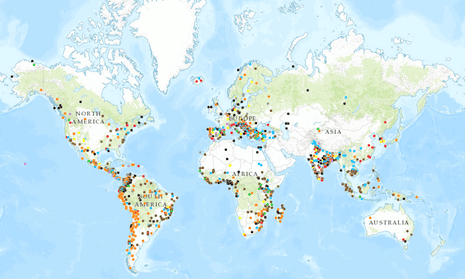

While statistics on strike action have been collected since the late 19th century for many countries and now globally by the International Labour Organisation, there is no one body that tracks the occurrence and frequency of mobilisations and protests related to the environment. It was this need to better understand and to track such contentious activity that motivated the Atlas of Environmental Justice project, an online interactive map that catalogues localised stories of resistance against damaging projects: from toxic waste sites to oil refining operations to areas of deforestation.

EJatlas aims to make ecological conflicts more visible and to highlight the structural impacts of economic activities on the most vulnerable populations. It serves as a reference for scientists, journalists, teachers and a virtual space for information, networking and knowledge sharing among activists, communities and concerned citizens.

The EJatlas was inspired by the work of participating Environmental Justice Organisations, such as Grain, the World Rainforest Movement and Oilwatch International, OCMAL, the Latin American Observatory of Mining Conflicts, whose work fighting and supporting impacted communities for 20-30 years now has helped articulate a global movement for environmental justice. The global atlas of environmental justice is an initiative of Ejolt, a European supported research project that brings together 23 organisations to catalogue and analyse ecological conflicts. The conflicts are entered by collaborating activists and researchers and moderated by a team at the Autonomous University of Barcelona.

At the moment the atlas documents 1,400 conflicts, with the ability to filter across over 100 fields describing the actors, the forms of mobilisation from blockades to referendums, impacts and outcomes. It resembles in many ways a medieval world map – while some regions have been mapped, others remain “blank spots” still to be filled. While much work remains to be done, the work so far offers several insights into the nature and shape of environmental resistance today.

Firstly, it highlights how those on the frontlines of these struggles are often not environmentalists – they are communities defending their livelihoods, the right to participate in decision-making and recognition of their life projects. Nor it this, as governments and companies try to paint it, about a balance between development and conservation. It is rather about the meaning of development itself, who is sacrificed in the name of development and who decides. Pollution is not democratic, nor is it colour blind.

Secondly, it shows how the globalisation of the economy and material and financial flows is being followed by the globalisation of resistance. Mobilisations are increasingly interlinked across locations: anti-incineration activists make alliances with waste-picker movements to argue how through recycling they “cool down the earth”. Foil Vedanta, a group of activists fighting a bauxite mine on a sacred mountain in India, follow the company’s supply chain to Zambia, where they reveal Vedanta is evading tax and spark street protests there. Trans-nationally, new points of convergence unite movements working on issues from food sovereignty to land-grabbing, biofuels and climate justice.

This globalising of concerns has led to more civil society participation in multi-lateral governance, but the outcomes are often based on voluntary guidelines. While investor-state dispute settlement mechanisms such as those embedded in trade agreements such as the proposed TTIP EU-US trade agreement can allow corporations to sue states, there is no way to hold corporate abusers to account. The Chevron case, where the company has managed to evade a 9.5 billion euro fine imposed by the top Ecuadorean courts for devastating the Amazon is only one example of this challenge.

The evidence shows that “corporate social responsibility” is not a panacea and that until corporate accountability can be enforced, successful “cost-shifting” will remain a defining feature of doing business.

Thirdly, the diversity of conflicts demonstrate that technical innovations and the greening of capitalism through “pricing nature” will not solve the environmental crisis. Biofuels, off-setting projects and even geo-engineering of the climate are leading to new conflicts as northern consumers occupy even more environmental space in the south – this time to absorb their atmospheric emissions. Naomi Klein has powerfully pointed out how looming climate chaos can only be addressed through a restructuring of the global economy, calling attention to inter-generational justice and the world we are leaving behind us. But the thousands of actually existing and localised struggles of environmental dispossession in the EJatlas are an even more potent call for the need for systemic change that addresses the unequal distribution of power and lack of democratic participation that are at the root of both social injustice and environmental degradation.

The danger such movements represent to powerful vested interests is attested to by the intensity of the violence and backlash wielded to repress them, with over 30% of cases shown on the map entailing arrests, killings, abuses and other forms of repression against activists. It is not an exaggeration in many countries to speak of a veritable “war against environmental defenders”.

Furthermore the number of violent conflicts is set to increase because the world’s remaining natural capital currently lies on or beneath lands occupied by indigenous and subsistence peoples. Communities who have nothing left to lose are willing to use increasingly contentious tactics to defend their way of life.

Beyond stories of disaster and degradation, the struggles documented in the atlas highlight how impacted communities are not helpless victims. These are not only defensive and reactionary battles but proactive struggles for common land, for energy and food sovereignty, for Buen Vivir, indigenous ways of life and for justice. The environment is increasingly a conduit for frustrations over the shape of capitalist development. Tracking these spaces of ecological resistance through the Environmental Justice Atlas highlights both the urgency and the potential of these movements to trigger broader transcendental movements that can confront asymmetrical power relations and move towards truly sustainable economic systems.

The up-to-date version of the atlas will be presented at the closing meeting of the Ejolt project in Brussels today where the project brings attention to the increasing persecution of environmental defenders and calls on European Union policymakers and parliamentarians to integrate environmental justice concerns into their policy agenda and move towards reducing the current atmosphere of impunity for environmental crimes.

Leah Temper is the coordinator and co-editor at EJAtlas. Follow @EnvJustice on Twitter.

Join our community of development professionals and humanitarians. Follow@GuardianGDP on Twitter.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion