Books In Conversation

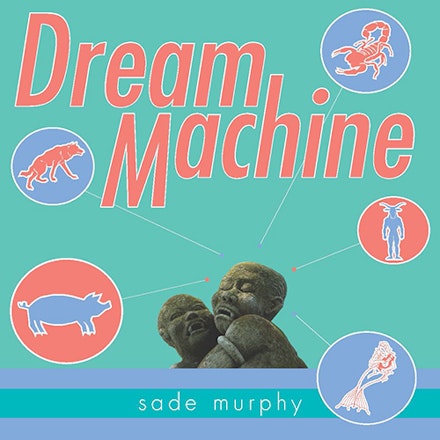

DREAM MACHINE

SADE MURPHY with Laura Stokes

Dream Machine

(co-im-press, 2014)

6. Do not pretend that you do not know how to sleep purely for the dream. Do not ignore the moon streaming high speed light into your window. Do not deny wishing that you were not sleeping alone. Do not fear the boogeyman, he is no more real than the lover borne in the depths of your dreams. Do not seek to control the way you do in waking life, for you will only ruin what prophecy you may receive. Do not knot yourself up over the meaning, let it instead fall through your fingers like sand.

25. Double fisting microphones on stage, wobbling a little. Breadth, a neon cock. That is all she wrought and do not forget it motherfucker. Fifteen left steps always to the third floor and or the rooftop fireworks that need to be lit with your smile. Cawfee crew cruise, Cheshire bronze tea cups cracking like sunburned skin off your nose, shaken like a baby.

—Excerpt from Dream Machine

Sade Murphy’s debut book of poetry, Dream Machine, is forthcoming from co•im•press this fall. There are 55 poems, with six poems each collected into nine sections. Numbers matter to Murphy here, but only in the way that the dreamer grasps at numbers on the verge of waking, seeking to realize some sort of universal order on the edge of consciousness. There is a sense in each poem that these were written on the borderland between dream and reality, where confusion and imagination coexist. This is a place Murphy has created for herself, where she can unmoor words from their old connotations and push them out into darker water. Characters move in and out of the poems—a lover and abuser called Him, a nightmare man, a cruel mother, and the dreamer, who both acts and is acted upon by her creations.

For the reader, these poems are both highly disorienting and highly intoxicating, like stealing looks inside the sleeping mind of a stranger. I wanted to know more about Murphy’s process of writing these poems, about what she has to say about the images and ideas of her dream world, so we sat down for a conversation in early October.

Laura Stokes (Rail): Tell me a bit about the process of composing the poems collected in Dream Machine.

Sade Murphy: Dream Machine began at the Vermont Studio Center, as a way to get myself writing everyday. The first 18 or so dream machines were written while I was there with 6 more written before the summer ended. I started out with a lot of structure, all these arbitrary rules for how I should behave, and it was good but stiff. As far as writing the poems goes, I’m a perfectionist (shamefully) and I’ll put off doing something until I feel like I can do it under near perfect conditions. There were dog-eared pages in my journals, scribbles of dreams written in dry-erase marker on my bathroom mirror, receipts with the beginnings of poems stuffed into my wallet, all accumulating until I could sit down and add them to the ongoing manuscript. Then as the project continued I broke free from those earlier constraints, let my hair down, stepped into my cunt and really drew from a broader range of experiences. The short answer would be to say that I wrote down what I dreamt. But there are dream machines, too, that are taken from conversations and happenings that felt like dreams, that were sort of incredible as they were occurring. The revision process is a big deal for me, and I’m always wondering as I’m writing how can I make this better, how can I push this poem to its absolute best iteration. It’s hard for me to describe because it’s something that feels very amorphous but ritualistic.

Rail: As I was reading this book, the line “Do not knot yourself up over the meaning, let it instead fall through / your fingers like sand,” struck me as a really wonderful directive about how to approach particularly the diction in these poems. How would you describe your approach to the language you used in this book?

Murphy: So true. I think that and the sentence right before, “Do not seek to control the way you do in waking life, for you will only ruin what prophecy you may receive,” was advice that I was also trying to take into the writing of these poems. I think in my daily life I really tend to agonize over the things I say and how I say them and how they may be received and interpreted or twisted, so communicating with people outside of myself comes with a lot of anxiety. The opportunity that I could be misunderstood can paralyze me a great deal and I let go of that fear while I was writing these poems. I used words and wrote things in these poems that made me slightly uncomfortable to read aloud later but at the same time made me feel dangerous and powerful in ways I hadn’t allowed myself to be up to this point. (Kind of a like a Beyonce-as-Sasha Fierce moment). No word was too obscene, taboo, obscure, or arcane. I used words from everywhere. During the latter half of the manuscript, I was watching a lot of nature and science documentaries, reading sociology casually, scrolling through the Oxford English Dictionary, making up words, twisting and combining words. I was also really inspired by poets who were doing fascinating things with language and translation in their own work. In the preface to All the Garbage of the World, Unite! Kim Hyesoon says, "I bend language on both sides to build a diction that undulates in a new way. Only then can poesy enter, transcendent, inside my poem." I felt excited and challenged by that.

Rail: It seems also like the sound of certain words really shaped these poems, too. I look at phrases like “Cawfee crew cruise” and “husked out hornets” from some of the poems and I wonder how much sound and rhythm mattered to you as you wrote.

Murphy: The aural experience of the poem is everything to me. I think that when I’m writing I always keep in mind how a poem will sound when I read it and a poem never feels finished until I’ve read it aloud, not just to myself but to another person. There’s something akin to breathing/speaking life into it that makes it real. I’ve been told that I have a really pleasing reading voice/style and I think it’s because I put so much energy into the way the poem sounds, the rhythm of the words, their weight. And it’s part of the revision process for me. I’ve definitely gone back and rewritten entire poems if it didn’t flow when I read them aloud, if it didn’t feel comfortable coming out of my mouth, if I couldn’t imagine myself reading it again and again. And I think that is another reason for a lot of the neologisms and portmanteaus that spring up. A professor once told me that “the image is the engine of the poem” and I’ve always held on to that. I kind of want to say that the rhythm is the chassis, but I don’t know that much about cars, so chassis just sounds like the right word for the analogy.

Rail: Thematically, I see some poems are about pursuit and escape, about capture/confinement and transcending that confinement. It seems to really link up nicely with your desire for freedom in the language. How intentional was that as you wrote them?

Murphy: I don’t think it was intentional. I think it’s just something that I’m always concerned with.

Rail: There’s also the issue of alienation in the poems. I wondered if the idea of seeking freedom—in language, in experience—was connected to that, especially in terms of writing as a woman of color in America.

Murphy: Definitely. In “Imagining the Unimagined Reader” Harryette Mullen says, “When I read words never meant for me, or anyone like me—words that exclude me, or anyone like me, as a possible reader—then I feel simultaneously my exclusion and my inclusion as a literate black woman, the unimagined reader of the text.” The entire essay resonates with me. Growing up I was ostracized for loving to read (in and out of my family), and reading was my main means of escape. But it’s interesting to think of myself in the context of Mullen’s essay, as the unimagined reader of so many of the texts that I pored over in high school. I think of most of the books I read on the AP Reading List in high school and whether those authors ever imagined a girl like me reading their books. It’s not such a stretch for authors like Morrison, Baldwin, and Angelou but they weren’t the authors I was assigned as a high schooler.

I notice how much policing marginalized bodies encounter. I worry about how much my poetry doesn’t center on the narrative of the dominant culture, and who it alienates because of that. I think about how white feminists (and other unfortunate souls) lose their shit over Beyoncé and/or Nicki Minaj and I see alienation as being part of that. Just on a lyric level, they are making music centered on their experiences and identities as women of color and the language they use reinforces that identity. And people are uncomfortable. If you had asked me even a year ago the same question I would have politely danced around it, but I feel very personally that if I (and people like me, black, women, queer, disabled, poor, fat, etc.) am going to be free, people with privilege are going to be alienated. It kind of makes me uncomfortable to even say that. A lot of Dream Machine was written as I dealt with feeling alienated in different realms of my life, so I feel like through the poems I go from alienated to alienator and it is not always fun but it is necessary. I want my voice and voices like mine to be heard over the pervasive noise of the mainstream.

Rail: What’s the importance of numbers to this project? How do you see those numbered sequences in terms of the dreams you’re describing?

Murphy: I’m obsessed with numbers and I’m a lapsed math nerd. The numbers are something in this project purely for my enjoyment. Even though I’m a mess of a person I love order, I love organization, so I see the numbers as a way to express that part of myself in the project.

Rail: I also wanted to ask you about the “Him” poems and other poems with sexual imagery. The male and female have very shifting relationships with respect to one another here.

Murphy: The character Him represents the male gaze and the multiple tropes of white boy masculinity, a sexual energy centered on mainstream male desires. I think this makes Him a fascinating focal point. Him is a destructive, confining presence even as Him is somewhat alluring. Him along with the nightmare man and the mother create a trifecta of forces/relationships both real and symbolic that the dreamer must navigate and extricate herself from to gain the freedom. They’re all using sex against the dreamer. Sex runs parallel to violence as a device/tool in the poems. In itself neutral, in the hands of various figures in the dreamscape it takes on a certain quality depending on that figure’s intent.

Rail: You’ve mentioned some artists and poets whose work influenced this book, but what other influences were important? How did the media and the larger world factor into the dreams as you experienced them?

Murphy: Very early on in the writing of Dream Machine I was reading a lot of Harryette Mullen’s work , I bought Recyclopedia at the recommendation of an artist I met at VSC. After I was at VSC I also visited NYC for four days and and went to the Frick and the Catholic Worker. I listened to Girl Talk nonstop. I saw the movie Tree of Life for my birthday and that prompted me to see The New World, another Malick film. I was going to mass every week. I think it was also around this time that I got into watching the cartoon Adventure Time. Toward the middle of the manuscript I saw Andrea Arnold’s Wuthering Heights and read a lot of Lara Glenum and Aase Berg. I saw Kara Walker’s exhibit at the Art Institute. Her work has had a huge impact on me. I also saw The Purge, and this was feeding into a time when I was beginning to shatter the illusion of respectability politics for myself. I realized that no amount of code-switching or even a degree from one of the top schools in the country could change the fact that I am black. I feel like I was finishing the manuscript during a very tumultuous time. And I mean personally as well as nationally and internationally. I was unemployed and even though I know it’s not the worst thing that’s ever happened to me, it opened the entire Pandora’s box of insecurities that I have about my ability to succeed and just to live the life that I want to live. It was also the first time in almost a decade that I would actually read the news, and it didn’t take me long to remember why I had stopped in the first place. I didn’t feel any justice in the world, only restlessness. I wasn’t sure how I felt about “God” anymore, I saw the ocean for the first time and I was too anxious to put more than a toe in. I spent too much time on Tumblr, read a lot of think pieces online. I was reading All the Garbage of the World Unite!, a graphic novel called Big Questions, Diaz’s This is How you Lose Her. I started getting into anime, at the recommendation of some friends I watched Attack on Titan and Sword Art Online. I watched a lot of documentaries: The Black Power Mixtape, Booker’s Place, Pageant, Paris is Burning, to name a few. I saw Upstream Color and The Skeleton Key. I played all three Mass Effects. Beyoncé released Beyoncé, which I still listen to weekly. Janelle Monae’s Electric Lady, The Roots’s Wise Up Ghost and Neutral Milk Hotel’s In the Aeroplane over the Sea. And Maya Angelou died. Reading I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings when I was twelve made me feel like someone like me, an economically poor black girl who was experiencing abuse at home, who did not have very many friends besides the books she read could do something great, could have a voice that others would listen to and want to hear. She was my first inspiration.

Rail: Finally, I was so intrigued by the relationship between the body and nature in these poems. By using dreams, you were really able to manipulate the physical landscape to suit the dreamer’s voice. What would you say is your approach to the relationship between body and nature? What are your thoughts about it?

Muphy: I love this question. I find myself obsessed with both bodies and nature, and the way that I feel they are similar beasts. Bodies and nature are permanently imprinted, continuously changed with what they experience. And I feel that they participate in this endless feedback loop. The dreamscape/landscape of the poems is informed by the body of the dreamer. The dreamer in turn is informed by the dreamscape, and moves and acts in relation to what occurs there. It builds and builds. Bodies and nature for me are vessels for bothness. They hold all these contrary forces in tension and harmony within themselves. Cruelty exists alongside justice exists alongside humor exists alongside contemplation exists alongside sensuality and sorrow and on and on. It all takes place in the body, it all takes place in nature, both being finite and endless.

Rail: Now that Dream Machine is out, what is your next project? What are your future plans?

Murphy: Oh goodness. Well this fall I’m applying to MFA programs, and I oscillate between being very ready for that and very nervous. I’m working on planning a reading tour for Dream Machine. I’m halfway finished with a project titled, self portrait. I started it at the same time as Dream Machine but it’s progressed a lot slower. I really like interdisciplinary work so I’m hoping the program I go to will be one that will allow me to continue my practice as a studio artist and social justice involvement.