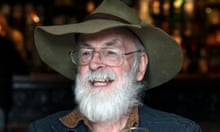

I want to tell you about my friend Terry Pratchett, and it’s not easy. I’m going to tell you something you may not know. Some people have encountered an affable man with a beard and a hat. They believe they have met Sir Terry Pratchett. They have not.

Science fiction conventions often give you someone to look after you, to make sure you get from place to place without getting lost. Some years ago I ran into someone who had once been Terry’s handler at a convention in Texas. His eyes misted over at the memory of getting Terry from his panel to the book-dealers’ room and back. “What a jolly old elf Sir Terry is,” he said. And I thought, No. No, he’s not.

Back in February 1991, Terry and I were on a book signing tour for Good Omens, a book we had written together. We were in San Francisco. We had just done a stock signing in a bookshop, signing the dozen or so copies they had ordered. Terry looked at the itinerary. Next stop was a radio station: we were due to have an hour-long interview on live radio. “From the address, it’s just down the street from here,” said Terry. “And we’ve got half an hour. Let’s walk it.”

This was a long time ago, in the days before GPS systems and mobile phones and taxi-summoning apps and suchlike useful things that would have told us in moments that no, it would not be a few blocks to the radio station. It would be several miles, all uphill and mostly through a park.

We called the radio station as we went, whenever we passed a payphone, to tell them that we knew we were now late for a live broadcast, and that we were, promise-cross-our-hearts, walking as fast as we could.

I would try to say cheerful, optimistic things as we walked. Terry said nothing, in a way that made it very clear that anything I could say would probably just make things worse. I did not ever say, at any point on that walk, that all of this would have been avoided if we had just got the bookshop to call us a taxi. There are things you can never unsay, that you cannot say and still remain friends, and that would have been one of them.

We reached the radio station at the top of the hill, a very long way from anywhere, about 40 minutes into our hour-long live interview. We arrived all sweaty and out of breath, and they were broadcasting the breaking news. A man had just started shooting people in a local McDonald’s, which is not the kind of thing you want to have as your lead-in when you are now meant to talk about a funny book you’ve written about the end of the world and how we’re all going to die.

The radio people were angry with us, too, and understandably so: it’s no fun having to improvise when your guests are late. I don’t think our 15 minutes on air were very funny. (I was later told that Terry and I had both been blacklisted by that San Franciscan radio station for several years, because leaving a show’s hosts to burble into the dead air for 40 minutes is something the powers of radio do not easily forget or forgive.)

Still, by the top of the hour it was all over. We went back to our hotel, and this time we took a taxi. Terry was silently furious: with himself, mostly, I suspect, and with the world that had not told him that the distance from the bookshop to the radio station was much further than it had looked on our itinerary. He sat in the back of the cab beside me white with anger, a non-directional ball of fury. I said something, hoping to placate him. Perhaps I said that, ah well, it had all worked out in the end, and it hadn’t been the end of the world, and suggested it was time to not be angry any more.

Terry looked at me. He said: “Do not underestimate this anger. This anger was the engine that powered Good Omens.” I thought of the driven way that Terry wrote, and of the way that he drove the rest of us with him, and I knew that he was right.

There is a fury to Terry Pratchett’s writing: it’s the fury that was the engine that powered Discworld. It’s also the anger at the headmaster who would decide that six-year-old Terry Pratchett would never be smart enough for the 11-plus; anger at pompous critics, and at those who think serious is the opposite of funny; anger at his early American publishers who could not bring his books out successfully.

The anger is always there, an engine that drives. By the time Terry learned he had a rare, early onset form of Alzheimer’s, the targets of his fury changed: he was angry with his brain and his genetics and, more than these, furious at a country that would not permit him (or others in a similarly intolerable situation) to choose the manner and the time of their passing.

And that anger, it seems to me, is about Terry’s underlying sense of what is fair and what is not. It is that sense of fairness that underlies Terry’s work and his writing, and it’s what drove him from school to journalism to the press office of the SouthWestern Electricity Board to the position of being one of the best-loved and bestselling writers in the world.

It’s the same sense of fairness that means that, sometimes in the cracks, while writing about other things, he takes time to punctiliously acknowledge his influences – Alan Coren, for example, who pioneered so many of the techniques of short humour that Terry and I have filched over the years; or the glorious, overstuffed, heady thing that is Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable and its compiler, the Rev E Cobham Brewer, that most serendipitious of authors. Terry once wrote an introduction to Brewer’s and it made me smile – we would call each other up in delight whenever we discovered a book by Brewer we had not seen before (“’Ere!’ Have you already got a copy of Brewer’s A Dictionary of Miracles: Imitative, Realistic and Dogmatic?”)

Terry’s authorial voice is always Terry’s: genial, informed, sensible, drily amused. I suppose that, if you look quickly and are not paying attention, you might, perhaps, mistake it for jolly. But beneath any jollity there is a foundation of fury. Terry Pratchett is not one to go gentle into any night, good or otherwise.

He will rage, as he leaves, against so many things: stupidity, injustice, human foolishness and shortsightedness, not just the dying of the light. And, hand in hand with the anger, like an angel and a demon walking into the sunset, there is love: for human beings, in all our fallibility; for treasured objects; for stories; and ultimately and in all things, love for human dignity.

Or to put it another way, anger is the engine that drives him, but it is the greatness of spirit that deploys that anger on the side of the angels, or better yet for all of us, the orangutans.

Terry Pratchett is not a jolly old elf at all. Not even close. He’s so much more than that. As Terry walks into the darkness much too soon, I find myself raging too: at the injustice that deprives us of – what? Another 20 or 30 books? Another shelf-full of ideas and glorious phrases and old friends and new, of stories in which people do what they really do best, which is use their heads to get themselves out of the trouble they got into by not thinking? Another book or two of journalism and agitprop? But truly, the loss of these things does not anger me as it should. It saddens me, but I, who have seen some of them being built close-up, understand that any Terry Pratchett book is a small miracle, and we already have more than might be reasonable, and it does not behoove any of us to be greedy.

I rage at the imminent loss of my friend. And I think, “What would Terry do with this anger?” Then I pick up my pen, and I start to write.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion