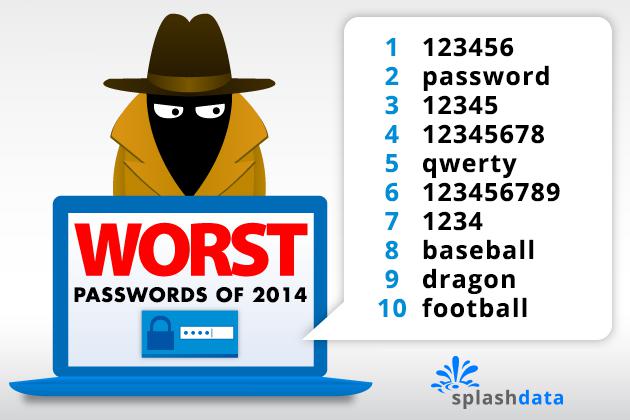

I recently worked with SplashData to compile its 2014 Worst Passwords List, and yes, 123456 tops the list. In the data set of 3.3 million passwords I used for SplashData, almost 20,000 of those were in fact 123456. But how often do you genuinely see people using that, or the second most common password, password, in real life? Are people still really that careless with their passwords?

While 123456 is absolutely the most common password, that statistic is a bit misleading. Although 0.6 percent of all users on my list used it, it’s important to remember that 99.4 percent of the users on my list didn’t. What is noteworthy here is that while the top passwords are still the top passwords, the number of people using those passwords has dramatically decreased. In 2011, my analysis showed that 8.5 percent had the passwords password or 123456, but this year that number has gone down to less than one percent. This is huge.The fact is that the top passwords are always going to be the top passwords, it’s just that the percentage of users actually using those will—at least we hope—continually get smaller. This year, for example, a hacker using the top 10 password list would statistically be able to guess 16 out of 1,000 passwords.

Getting a true picture of user passwords is surprisingly difficult. Even though password is #2 on the list, I don’t know if I have seen someone actually use that password for years. Part of the problem is how we collect and analyze password data. Because we typically can’t just go to some company and ask for all their user passwords, we have to go with the data that is available to us. And that data has problems.

Anomalies are more prominent

As we saw, user passwords are improving, but as percentages of common passwords decrease, anomalies begin to float to the top. There was a time that I didn’t worry too much about minor flaws in the data, because as my data set grew, those tended to fall to the bottom of the list. Now, however, those anomalies are becoming a problem.

For example, when I first ran my stats for 2014, the password lonen0 ranked as #7 in the list. Looking through the data, I saw that all of these passwords came from a single source, the Belgium company EASYPAY GROUP. The organization had its data leaked in November of 2014. And looking through the raw data, it appears that lonen0 was a default password for 10 percent of their users that failed to set to something stronger. It’s just 10 percent of users from one company, but that was enough to push it to the #7 most common password in my data set.In 2014, all it takes for a password to get on the top 1,000 list is to be used by just 0.0044 percent of all users.

Single sets of data vs aggregated data

There are numerous variables that affect which passwords users choose, and therefore many people like to analyze sets of passwords dumped from a single source. There are two problems with this: first, we don’t really know all the variables that determine how users choose passwords. Second, data is always skewed when you analyze a single company as we saw with EASYPAY GROUP. If you look at password dump data from Adobe, you will see that the word adobe appears in many of the passwords.

On the other hand, if we aggregate all the data from multiple dumps and analyze it together, we may get the wrong picture. Doing this gives us no control variables, and we end up with passwords like 123456 on the top of the list. If we had enough aggregated data that wouldn’t be an issue, but what exactly is enough data?

Cracked passwords are crackable; Hacked companies are hackable

Since most of the data we are looking at comes from password leaks, it is possible that 123456 tops the list simply because it is the easiest password to crack. Perhaps some hacker checked tens of thousands of e-mail accounts to see if the password was 123456 and dumped all positive matches on the Internet. In fact, part of the reason I only analyzed 3.3 million passwords this year is due to a large number of mail.ru, yandex.com, and other Russian accounts that had unusual passwords such as qwerty and other keyboard patterns. Here is the top 10 list, including all the Russian e-mail accounts:

1. qwerty

2. 123456

3. qwertyuiop

4. 123456789

5. password

6. 12345678

7. 12345

8. 111111

9. 1qaz2wsx

10. qwe123

While these are common passwords, the Russian data was highly skewed, which made me suspect that these were either fake accounts or hacked by checking only certain passwords. So while 3.3 million passwords isn’t a huge dataset to analyze, it is a clean set of data that seems to accurately reflect results I have seen in the past.

The other problem is that when a company gets hacked, often it is because they have not properly secured their data. If they have poor security practices, this could affect password policies and user training, which might result in poor quality passwords.

Unfortunately, we do not know to what extent crackable passwords and hackable companies affect the quality of the password data we have to analyze.

No indication of source

Again, when we work with publicly leaked passwords, we often don’t know the source of the data. We don’t know if the passwords are from some corporation with strict password policies, if they come from hacked adult sites where many users are choosing passwords such as boobies, or if they are hacked Minecraft accounts where a large chunk of the users are kids or teenagers. We don’t know if the data came from keyloggers or phishing or password hashes.

We also don’t know when users set these passwords. When Adobe had 150 million user accounts leaked, clearly those passwords were from accounts and passwords created years ago. We do know that users are slowly getting better with their passwords, but if we don’t know when they set these passwords, it is impossible for us to gauge that progress.

These are all significant variables and therefore make it impossible for us to get an accurate picture of which passwords people truly are using where and when.

reader comments

89