Summarising the findings of a new report into poverty in the UK, Katie Schmuecker highlights the need to go beyond conventional approaches to poverty reduction. She discusses the changing face of poverty, with the fall in pensioner poverty and rise in poverty of those living in working households.

Summarising the findings of a new report into poverty in the UK, Katie Schmuecker highlights the need to go beyond conventional approaches to poverty reduction. She discusses the changing face of poverty, with the fall in pensioner poverty and rise in poverty of those living in working households.

With conference season in full swing and the finishing touches being put to manifestos, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation has issued a challenge to all the political parties to put reducing poverty at the heart of their election promises. But to succeed in sustainably reducing poverty, there is a need to rethink our approach to it.

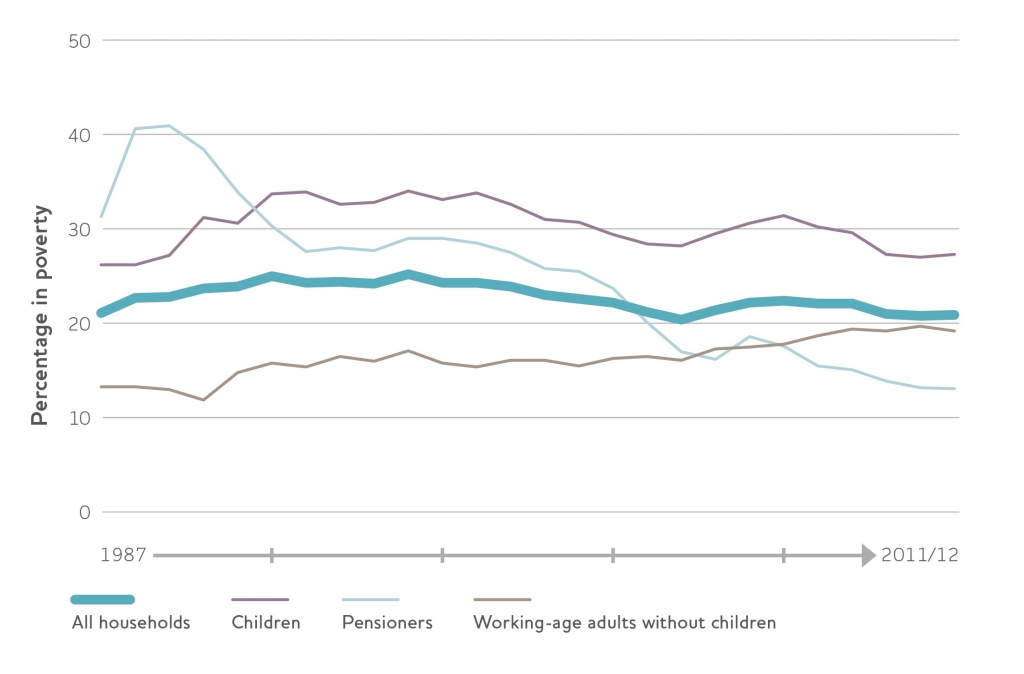

A UK Without Poverty sets out how past attempts at poverty reduction have failed, and overall poverty levels have stayed fairly flat for the last 25 years (see graph). The prevalence of poverty among different groups has changed, however, falling sharply for pensioners and rising for working age adults without children. To make real progress a comprehensive strategy to sustainably reduce poverty for people of all ages is needed.

Figure 1: Overall poverty levels have stayed fairly flat for the last 25 years

Note: Poverty defined as percentage below 60 per cent contemporary median income after house costs (AHC).

Source: IFS

Why tackle poverty?

Tackling this longstanding problem should be an urgent priority for whoever forms the next government because poverty is a cost the UK cannot afford. Child poverty alone costs the UK £29 billion a year in extra spending on benefits and services to deal with the consequences of poverty, lost tax revenue and lost earnings to individuals. Furthermore, growing up in poverty has a scarring effect, with implications for a child’s sense of self-worth and likelihood of realising their potential at school. It also increases their risk of poverty in adult life.

Overall, poverty wastes people’s potential and puts a strain on the public purse. It means the UK economy does not function as well as it could, as it cannot draw on all the resources available to it. Public money that is diverted to deal with the consequences of poverty could be spent on boosting growth through investment in skills or updating infrastructure if poverty was reduced.

But poverty doesn’t only carry an economic cost: it also affects personal lives and relationships. The stress it causes and the lack of control people feel has far-reaching consequences. It can trigger depression and anxiety and the strain increases the risk of relationship problems and breakdown – which can also lead to poverty, as reflected in the high rates of poverty among lone parents.

The urgency of the problem is underlined by that fact that if we don’t start doing something different, poverty is expected to increase. The IFS forecasts one in three children and one in four working age adults will be living in relative income poverty (after housing costs) by 2020.

What is poverty and how can it be tackled?

To successfully and sustainably reduce poverty requires a clear understanding of what poverty is, who has a part to play in addressing it, and solutions based on evidence. JRF defines poverty as when a person’s resources are not enough to meet their basic needs. This includes the need to be part of society, by being able to participate in common customs and activities – like buying a birthday present for your partner or sending your child on a school trip.

Defining poverty in this way means that there are two things to be done to tackle it: increasing the resources available to a household, or reducing the costs of meeting their needs. Conventional approaches to poverty reduction have relied heavily on the tax and benefit system and the role of the state. Both will always have an important part to play, but they cannot succeed alone. The net must be cast wider.

For example, the cost of essential goods and services has been a particular problem for low income households in recent years. JRF research shows the cost of a basket of essentials has increased by 28 per cent since 2008, faster than the official rate of inflation (the Consumer Prices Index), which increased by 19 per cent, and the average wage, which only increased by 9 per cent. Over the same period wages have been stagnant and in- and out-of-work benefits cut in real terms. This has resulted in a gulf opening up between family incomes and the cost of an acceptable living standard. Ensuring markets work well for low income consumers and they are able to access essential goods and services must form part of a strategy to reduce poverty.

Furthermore, the face of poverty is changing. Half of people experiencing poverty today live in working households. This is a shift public policy has yet to catch up with. This is particularly problematic as work ought to offer the best route out of poverty for most people, yet the nature of work at the bottom of the UK labour market acts as a barrier. Jobs that are low paid, low skilled, insecure and offer no progression and insufficient hours contribute to in-work poverty.

Indeed, to reduce poverty there is no one single response that will succeed on its own. A comprehensive strategy must recognise that where people live; whether they are able to fulfill their potential; the choices they make; the nature of jobs at the bottom end of the labour market; the cost of essential goods and services; the workings of the tax and benefit system; and the functioning of public services all have a part to play. It must also recognise the dynamic nature of poverty, which differs at different stages of life, meaning thought must be given to policies that have an impact now and those that provide insurance against future events.

These are some of the early findings to come out of JRF’s programme of research to develop evidence based strategies to sustainably reduce poverty across the UK and devolved administrations. This summer saw the conclusion of the first phase of this work, with the publication of a collection of 33 research summaries assessing the evidence base for solutions to poverty. The next phase will see more detailed policy development and modelling work to test different approaches.

Poverty is a problem we can solve

Poverty is real, but it is not inevitable. Looking at pensioner poverty should provide some optimism for what can be achieved. There was a time when reaching retirement meant a sharply increased poverty risk, but pensioner poverty has fallen steadily in recent decades, helped along by concerted action from successive governments and strong cross-party support. With the same ambition, consensus and long-term commitment, poverty among people of all ages could be similarly reduced. And not only would that be good for people who experience poverty; it would be good for everyone.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting. Featured image credit: κύριαsity

Katie Schmuecker is a policy and research manager at the Joseph Rowntree Foundation. She manages their research on the future of the UK labour market. She tweets from @KatieSchmuecker

Katie Schmuecker is a policy and research manager at the Joseph Rowntree Foundation. She manages their research on the future of the UK labour market. She tweets from @KatieSchmuecker

Very insightful.