The Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) had such a furtive existence that many senior officers knew nothing about it. An undercover unit, it infiltrated hundreds of groups across the political spectrum over 40 years.

The SDS recruited very informally – a tap on the shoulder or a discreet word in a corridor. Recruits would vanish into a secret undercover world for years, handing in their warrant cards and never visiting a police station.

They adopted elaborate fake identities, equipped with false documents such as tax records and driving licences.

Descending deep undercover, they lived the life of a committed political campaigner, only returning to their real families for one or two days of the week.

They have been likened to the "human equivalent of a covert listening device" by Mick Creedon, the Derbyshire chief constable given the task of investigating the conduct of the unit between 1968 and 2008. They targeted political groups and "hoovered up" all the knowledge and information that they gathered to report back to their bosses in Special Branch.

But that flow of intelligence, it has now been revealed, included the activities of 18 often grieving families fighting for justice from the police between the mid-1980s and 2005.

In one sense, it should be no surprise that Special Branch wanted to hoard this information – that was, after all, their job.

Among its responsibilities was to gather intelligence about political threats to the established order, whether it be grieving families wanting to know the truth about police misconduct or activists wanting to bring about radical change.

In a rare moment of frankness Merlyn Rees, who was home secretary in the 1970s, said the role of Special Branch was "to collect information on those who I think cause problems for the state".

Creedon has harsh words for the leaders of Special Branch, blaming them for allowing the SDS undercover officers to gather intelligence on the families in what he calls "a largely unchecked and unregulated way".

Those in charge of the undercover officers operated, he says, in such secrecy and isolation from the rest of the police that outsiders were unable to see how the unit was running out of control. It is a classic case of how the secret state behaves badly when it believes that no one will ever find out what it is up to.

That we know about the unit, and its wrongdoing, is the result of the detective work of many of those who were infiltrated and abused by the unit, revelations in the Guardian over the last three years and – not least – the decision of one of the unit's most dedicated operatives to break ranks and blow the whistle.

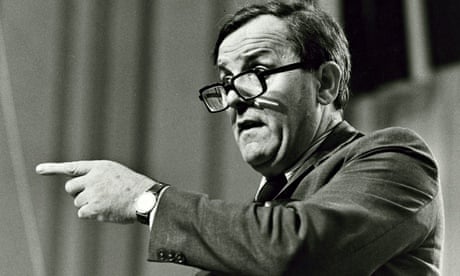

Peter Francis, who infiltrated anti-racist groups between 1993 and 1997 for the SDS, has shed unprecedented light on his former unit, illuminating, for instance, how undercover officers routinely formed sexual relationships with campaigners and stole the identities of dead children.

It was he who disclosed how the SDS gathered intelligence on the so-called 'black justice' campaigns.

He is now urging the police to give the families "full and unhindered access" to all the SDS and Special Branch records held on them "so that they themselves can determine what the purpose of the spying actually was". After all, he added, "it is not as though they are organised criminals, terrorists or pose any form of threat to national security".

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion