In early 2006 I was 39, living in Bristol and working at one of the best robotics labs in the world. I had become increasingly obsessed with what life would be like if civilisation collapsed, and thought that I could find out by setting up a community that acted as if it already had. I created a website called An Experiment In Utopia, and announced that I was creating a novel kind of community based on three main ideas. I wrote:

1. It will be a LEARNING COMMUNITY – each member must have a distinctive skill or area of knowledge that they can teach to the others.

2. It will be a WORKING COMMUNITY – no money is required from the members, but all must contribute by working.

3. It will be strictly TIME-LIMITED. This is not an attempt to found an ongoing community. The experiment will last 18 months. Members may stay for months, but may also come for as little as two weeks.

In a word, think of a cross between Plato’s Academy and The Beach.

I asked people to send me a 200-word email telling me who they were, and what they could offer the community. Before long I had received several hundred applications. Aged 18 to 67, a roughly equal mix of men and women, they came from a wide range of backgrounds. They included an ex-Royal Marine turned shoemaker, a retired schoolteacher who had spent time with the Inuit, and a graffiti artist from Belfast.

There was Agric, a self-employed computer technician in his early 50s, who lived in Slough and grew his own vegetables. His first email to me concluded with a heads up about the dire consequences of peak oil: the moment when global oil production starts to decline. Agric was not alone in thinking peak oil was imminent. I soon found out it was a common belief among doomers, or people who believe a global catastrophe will happen within the next few years.

At the other end of the optimism scale are boomers, or cornucopians, who believe continued technological progress will solve all our problems. For a long time I had counted myself firmly among them. Like most of the other researchers I met at the Bristol Robotics Laboratory (then known as the Intelligent Autonomous Systems Lab), I started off with grand ambitions about building robots that would be able to run around, hold intelligent conversations and free people from dull, dirty and dangerous jobs. Of course, I knew that there would be big challenges, but I hadn’t realised that the biggest would be energy. The most advanced intelligence won’t get you very far if you run out of power.

After a few months in Bristol it struck me that, in this sense (as in others), robots were rather like human societies. Many societies have collapsed because their energy requirements began to outstrip their resources. And despite all the protestations about the dangers of climate change, the world as a whole seemed incapable of doing anything about it.

Instead of trying to imagine from the comfort of my armchair what life might be like if civilisation collapsed, I decided to act it out, with the help of some volunteers. We would grow our own food, make our own clothes, and do everything else necessary to survive, without any of the resources of our modern world. It wouldn’t simply be another hippy commune – it would be an exercise in collaborative fiction. We would imagine the end of the world.

I received an email from a man called Adam. He said he had heard about my experiment, and was drawn to my vision. I was intrigued, and invited Adam to visit the lab a few days later. I guessed from the email that he was a bit eccentric, but nothing prepared me for the ragged traveller who greeted me at the reception desk. In his early 50s, he was dressed in a British Airways blanket and a cowboy hat, with a feather poking out of the hatband. His grey beard and gnarled face made me think of Gandalf from Lord Of The Rings.

I would later learn that Adam was not his real name (or, “not the name the humans gave me”, as he put it), but one he had given himself when he “left the world of man”, in 2004. He had given away everything he had except for a few hundred pounds, and within three weeks, all the money was gone. Now he wandered the country from one community to another, seeking to promote his strange gospel, a mishmash of New Age ideas and an idiosyncratic interpretation of Christianity that drew heavily on Dan Brown. But at that first meeting, Adam told me none of this. He told me he could build us some yurts.

We agreed to meet when I had found a location, I had an old friend who could help me with that. I met Romay at Southampton University in 1987. In 2000 she bought and renovated the old farmhouse where she had spent her childhood. Her brother had inherited the farmland around it, on which he now raised some of the best beef cattle in Scotland. I asked her if he might be willing to lend me some of his land. “I think you could probably persuade him,” she said. “And I know the perfect place.”

A few weeks later I travelled to Romay’s farmhouse and Alastair’s farm, which lay on the northern shores of the Black Isle, north of Inverness. A stream cut through the fields and formed a small valley, densely overgrown with trees and bracken. Here, with the surrounding farmland out of sight, you suddenly felt very far from civilisation. There was a small waterfall we might use to generate electricity. Slopes either side of the stream might be good to terrace for fruit trees and berry bushes. The valley widened to form a flat area either side of the water that might provide a suitable site to set up our camp.

Above the valley lay a large potato shed with stone walls and a roof of rusty corrugated iron. This, Romay suggested, could be a communal eating and cooking area. Near the potato shed was an acre of scrubland where we could grow our crops and keep a few pigs and chickens. The land was stony and would need a lot of preparation before we could plant anything. But the soil was rich and dark. I had no idea about farming. The only thing I had grown was a cannabis plant, and that was more out of curiosity than for any practical purposes. I was blissfully unaware of how ill-suited I was to that way of life.

As the spring of 2006 turned into summer, and the time to leave for Scotland drew nearer, I was becoming more of a committed doomer. The experiment was becoming more than just a simulation; it was a preparation for the real thing. The more I contemplated the idea of global collapse, the more it became not just a possibility, but a near certainty.

By July, I was finally ready to embark on my journey. My house was sold. I’d quit my job. Most of my worldly possessions had been sent to Scotland and were now piled high in an old shipping container in a muddy field. I drove up with my cat, Socrates. When I got up that first morning and emerged from my tent, blinking in the early sunshine, I felt a sudden rush of joy. I stood and looked around me at the little clearing by the river. Soon there would be two yurts here, and a campfire, with wooden benches arranged round it. In the evenings we would gather to eat our supper as the fire blazed and some pot bubbled away. At the centre of it all, unassuming but indisputably wise, would be me, the founder, loved and revered by my fellow utopians.

A week later I met Adam at the bus station in Inverness. He was wearing a brown felt trilby with a feather, a sleeveless, fur-trimmed sheepskin jacket and black leather shorts worn over long red cycling pants. We started putting the yurts up right away.

That evening, we celebrated Adam’s arrival and the completion of the first yurt with a delicious stew of beans and tomatoes that we cooked over an open fire. The sun doesn’t set until very late in the Highlands in summertime, but by the time we finally went to bed it was quite dark, and I had to find my way back to my little tent with the aid of a torch. I wondered how I would manage when all the batteries had run out, which would be bound to happen sooner or later, after civilisation collapsed. Would I carry around a flaming stick, like a Viking, or would my eyes become better at seeing in the dark? As I snuggled into my sleeping bag, I thought I heard a wolf howl in the distance. I heard it again, clearer this time, and louder. Suddenly, I was afraid. I decided to gather up my sleeping bag and move back to the fire.

In the dim moonlight, I could just about make out the silhouette of a man. From the shape of the hat, I recognised Adam, standing upright by the river, his head tilted backwards, as he let out another long, bloodcurdling howl.

It was a relief when the second volunteer arrived. Agric pulled up around midday in his battered old Volkswagen camper van, packed with plants, gardening gear and other assorted implements. With his wispy white hair and impish expression, he seemed like another character out of Tolkien: a hobbit on speed. He chatted excitedly as we walked down to the yurts together.

“The land available for growing crops is flatter than I thought, which is good, but we’ll have to move those pigs!”

The pigs, which Romay had kindly provided, were currently camped on the bit of land that Agric wanted to plant with a wide variety of crops. Adam, Agric and I sat down to make a fire and boil some water for a cup of tea. Of course, there wouldn’t be tea in Scotland after civilisation collapsed (long-distance trade would take years to re-establish) but we told ourselves that we had a stash of teabags left over from before the crash.

“We can make allowances for a few small pleasures, providing they fit with the scenario,” said Agric.

“Sure,” I nodded. “But there are limits. We can’t just buy a crate of wine every week and tell ourselves that we keep finding well-stocked cellars in the abandoned farmhouses nearby.”

“Don’t worry, we’ll be making our own wine very soon,” said Agric.

Adam grimaced. “I don’t think we should allow alcohol,” he said, sternly. “This should be a pure place, for pure souls.”

“Oh, come on, Adam!” chirped Agric, amiably. “We’ll need an occasional drink to survive the apocalypse!”

It didn’t take me long to realise that Agric was a fully committed doomer. For him, the scenario we were acting out at the Utopia Experiment was not just a collaborative fiction; it was preparation for the real thing. But if Agric was so sure civilisation was about to collapse, why hadn’t he sold his house in Slough?

The ranks of our fledgling community began to swell with the arrival of new volunteers. There was Nick, an 18-year-old who had just finished school and was taking a gap year before going to Cambridge University; David, the ex-Royal Marine; and Harmony, a 23-year-old musician completely unfazed at being the only woman on site when she arrived. A few days later, my friend Angus arrived. We established a good set-up.

Two yurts stood proudly by the river alongside an open-air wooden platform that Adam had built, without knowing quite what it was for; it now served as a place to cook and eat lunch. The pigs had done a good job of preparing the ground for Agric’s vegetable patch, and we had begun to renovate the potato shed with the intention of turning it into a kitchen, dining area and general indoor workspace. We sowed broad beans, garlic, onions and shallots. Meanwhile, Adam worked alone on a little heart-shaped herb garden down by the yurts. The numbers changed often – we had a revolving door policy, and a diverse bunch of people, from a retired grandmother to enthusiastic students.

Several of the volunteers had already raised doubts about the scenario I had sketched out as a framework for the experiment. By the time disaster struck, we would be in an enviable position; with our own supply of food and water, a magnet for less well-prepared survivors. Sooner or later we would have to stop people from coming in. What if they were starving? What if they were armed?

When the topic came up one evening, Pete, a student, suggested we simulate an attack on the community.

“Personally, I like the idea of utilising booby traps,” mused Angus. “How about a couple of longbows trained on visitors as a deterrent?” suggested Pete.

Angus nodded: “What about organising workshops in bomb-making?’ As time went on, I worried that the subject seemed to exert such fascination. New solutions to the problem would be suggested, but the conversation always seemed to end with what became Angus’s stock phrase: “Attack dogs and pipe bombs”.

By early winter, the days were getting noticeably shorter and the sky was increasingly overcast. Whether due to the lack of light, or to the weeks of hoeing and digging, I was beginning to feel weak, tired and lonely. I wasn’t eating properly either; by the time I stopped work for lunch I was usually too tired to cook, so I would end up simply eating a few slices of Agric’s homemade bread, nowhere near enough to keep me well fed. I began to lose weight.

The only way to keep warm was to keep active, by chopping wood or carrying water or tightening the ropes on the yurt. Or to stoke up the stoves, tie down the canvas flaps that served as doors, and take refuge inside the yurts for hours on end, until your muscles cried out for exercise, or your bladder could wait no more.

Hard though it was to live in such primitive conditions in wintertime, it felt authentic, and satisfying. It was what I had dreamed about. But there was one thing I hadn’t foreseen – the arrival of my girlfriend Bo. We had met through a friend just before I left for Scotland, and fallen in love. She arrived just before my 40th birthday, with her daughter, and I rented them a little cottage a few miles away. Soon I was heading over to see her every day or two, staying the night.

I felt pulled in opposite directions, torn between my desire to spend time with Bo and my wish to tough it out in Utopia, to see if I could weather the whole winter. Whenever I was at Utopia I would worry about Bo, and whenever I was with Bo I would feel I was cheating, sneaking off to a warm cottage while Adam shivered in his yurt, or Agric chopped wood. They never said a word. Indeed, Agric would tell me that she needed me, and he could cope just fine.

I had built not one but two little communities, and yet I was not fully a member of either. I cherished the fantasy that Bo might move to Utopia in the spring, that my two little families would become one big tribe, and it was in that spirit that I asked her to marry me.

We got married on a sunny morning in February. Bo had invited some of her friends from London, and I invited my mother and sister. The two of them flew up to Scotland the day before, and I can still remember the look of horror on their faces when I proudly showed them the site of my experiment. I stood in a register office in the nearest town, with Bo next to me and a motley crew of guests seated behind us. I was dressed in a shabby suit . And there was Bo, looking fabulous in a pretty white dress.

I continued to split my time between my two lives. One day in early April, I got a letter from the Highland Council. “During a recent visit,” it said, “it became apparent that development has commenced prior to the granting of planning permission.” The letter also asked me to “halt all works on site” until such permission was granted.

Civilisation was like quicksand. The more I struggled to break free from it, the more it sucked me back in, suffocating me with its rules and regulations. One of the biggest attractions about the experiment had been the promise of a life free from paperwork. Suddenly I was drowning in it.

I had made a tidy profit when I sold my house, and I had been using this money to fund the experiment. It didn’t cost very much to buy the basic vegetables needed in the first few months before eating our first crops, but it all added up, and there was the rent for Bo’s cottage, and a hundred other little things like stoves, and seeds, and spades and shovels and axes and fleeces and candles and planks and hammers and saws, and all the other things we had apparently managed to salvage from the wreckage of civilisation.

Nine months after arriving in Scotland, my money was fast running out. I wasn’t even sure I would have enough to keep the experiment going for the whole 18 months.

Meanwhile, relationships were becoming strained. Adam and I didn’t always see eye to eye, and he started threatening to leave Utopia and take one of the small yurts with him.

“It’s not your yurt to take, Adam,” I said. “It belongs to the experiment. And it’s not your experiment, either.”

“I’m doing a different experiment,” he replied. “You do yours here in the barn area. I’ll do mine down there, by the river. That will be Adamland. I don’t believe in all this stuff about civilisation collapsing anyway. I just want to live in accordance with the wishes of the Great Spirit.”

“That’s not going to happen. And unless you can join in properly, and stop messing everything up, you’ll have to leave.”

“Don’t worry,” Adam snarled. “I’m going.”

The next day, he was gone. I never saw him again.

Nearly a year after I arrived in Utopia, we were still making regular runs to the supermarket to supplement our meagre crop. At first I had justified these shopping trips by arguing that in the immediate aftermath of a global catastrophe, the survivors would be able to scavenge supplies from local houses and abandoned shops. But the grace period offered by the leftovers of civilisation would last only so long, and the survivors would have to make sure they could grow or catch all their own food by the time the packaged stuff ran out. Now, almost a year into the experiment, every trip to the supermarket felt like a betrayal. How valuable a simulation of life after the collapse of civilisation could it be, if we were still popping down to Tesco every week?

To address this problem, I came up with the concept of Post-Apocalyptic (PA) rating. If something had a PA rating of 100% it meant that it could be done, or could exist, in exactly the same way after the crash – baked potatoes, for instance. We would try not to buy anything with a PA rating of less than 100%. But it still felt like cheating.

My doubts were growing and I came to the biting, shattering conclusion that the whole experiment had been a huge mistake. I recall waking up one night, my heart beating rapidly, as if icy fingers were clawing at my chest. I sat up in my sleeping bag and tried to calm down, but as I shivered in the cold I wished I were back in my old home, with a normal job and a regular income. I no longer understood why I had moved to Scotland to spend all my money on this madcap scheme. And when the experiment was over, I would be destitute and homeless.

I sank deeper into depression. I found myself standing at the door to Bo’s cottage, having a conversation that ended our relationship. I consoled myself with the thought that I could now spend all my time at Utopia, but my constant presence there only made my mood darken. I felt trapped. Ashamed of myself, I took to wandering off into the woods to hide. Meanwhile, the experiment rumbled along and everyone seemed to get more enthusiastic, making it even harder for me to question out loud the value of what we were doing.

One morning I awoke to find myself curled up under some bushes, my clothes wet with the early morning dew. I can’t say why I had fallen asleep there, but it was something to do with my madness. I crawled out from the ditch and stood up slowly, my body stiff and sore. It was a grey, misty morning, and there were no signs of life in Utopia just down the gently sloping hill. I trudged away in the opposite direction, towards Romay’s farmhouse.

“What on earth have you been up to?” she said, when I stumbled into her kitchen, bedraggled.

I slumped into a chair. “I’ll make you a cup of tea,” she said. “Oh, and a letter came for you.”

I opened the envelope and scanned the contents. It informed me that I had an appointment with a psychiatrist. I had been to see a local GP a few weeks before. But when I explained my predicament, he seemed out of his depth, and told me I needed to see a psychiatrist.

Romay seemed unimpressed. “When is it?”

“Today.”

As I waited in the hospital reception, I looked around at the clean white walls, the comfortable chairs. It all seemed very alien. I felt like an anthropologist who had just spent a year with an indigenous tribe on a Melanesian island and was finding it hard to readjust to the modern world.

The receptionist called my name, and I walked down the corridor A tall blond woman stood up to greet me. “Hi, I’m Dr Williams,” she said. “What brings you here today?”

“I feel like killing myself,” I said.

Gradually, I told her about the past year, about the Utopia Experiment, about Bo, about everything. Finally, she laid her pen down and asked if she could go and fetch a colleague.

A few minutes later she returned with a smartly dressed man.

“This is Dr Satoshi,” she said. “He’s the senior psychiatrist here.”

Dr Satoshi sat down beside me.

“Dr Williams has told me a bit about your story,” he said. “I’d like to offer you a bed here for a few days.”

Tears began to well up in my eyes. The thought of staying here, in the hospital, filled me with a sense of relief. But it also scared the hell out of me. “OK,” I said, “I’ll stay.”

Dr Satoshi looked pleased. But just as he reached for a file on his desk, I changed my mind. “Hold on!” I muttered. “I don’t think I will stay here after all.”

Dr Satoshi looked across at Dr Williams. She nodded.

Dr Satoshi cleared his throat. “You’re clearly incapable of making decisions,” he said. “We’re going to detain you under the Mental Health Act, for your own safety.”

And that was it. I was no longer a free man. And I felt curiously relieved.

It was over a year before I felt completely normal again, and even longer before I could be honest with myself about what had happened in Utopia. After a month in hospital I was functional enough to return to the site to tell the volunteers it was all over. As I spoke to them, it became clear they had no intention of leaving. The idea that they would just ignore me and carry on hadn’t crossed my mind. So early one morning I crept out of my yurt, packed up my things, and left.

Six years later I was teaching at a university in Ireland when one of the volunteers tracked me down. I learned that Agric was still spending half the year living on what the remaining volunteers had renamed the Phoenix Experiment, visited by several other volunteers. So a phoenix had risen from the ashes. There was even a rumour that they were waiting for me to return.

I’m still glad I did it, and not just because I’m not living in a field in Scotland any more. I learned that I’m not invincible, but also that I’m stronger than I thought. And I’m not afraid of the collapse of civilisation, either: not because I no longer think it will happen – who knows? – but because I’ve looked that possibility squarely in the face.

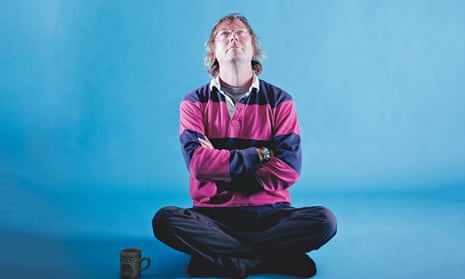

This is an edited extract from The Utopia Experiment by Dylan Evans, published by Picador on 12 February at £14.99. To order a copy for £11.99, go to bookshop.theguardian.com or call 0330 333 6846.

Who’s who, come the apocalypse

Boomer Someone who thinks that technological progress will continue indefinitely and make us all richer and happier.

Catastrophism The belief that the world is heading towards an economic, environmental, social or spiritual collapse, and a new and better world will emerge from the ashes of the old one.

Cornucopian See boomer.

Declinism The belief that things are getting worse, compared to a former Golden Age. Popular candidates for the start of this decline include the Industrial Revolution (romanticism) and the birth of agriculture (primitivism).

Doomer Someone who believes catastrophe is imminent, and that civilisation will collapse.

Millennialism The belief that the imperfect world we live in will soon be destroyed and replaced with a better one.

Prepper Someone who is actively preparing for a disaster by stocking up on food and other items. The disaster could be anything from an extended power cut to a global catastrophe; some preppers are preparing for a relatively small disaster. Primitivism The belief that modern civilisation makes people unhappy, and that the cure lies in returning to a more simple life.

Rewilding The process of reversing human domestication by relearning primitive skills such as hunting and gathering.

Survivalist Someone who is stocking up so they can survive. Unlike preppers, they tend to think the disaster will be global, or national at the least.

Transhumanist Someone who hopes that future developments in technology will radically transform human nature for the better.

Dylan Evans

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion