In just four years, Uber has constructed an intimidating profile. It operates in 45 countries around the world and well over 100 cities. It services millions of customers and employs hundreds of thousands of drivers. In June, Uber snagged $1.2 billion in financing that valued it at $17 billion—the biggest tech startup funding round ever.

That Uber has compiled such impressive numbers is fitting for a company that’s avowedly built on data. For all its talk of “ride-sharing,” Uber is essentially a for-hire car or taxi service like any other, but for one golden insight: how to make taxi-ing more efficient. Using an algorithm of its own making, Uber has introduced drivers and customers to dynamic pricing—the idea that rides should cost more when demand is greater. In doing so, Uber has embraced the free market and systematically chipped away at inefficiencies in car services by bringing supply in line with demand. That algorithm—and the data that make it possible—underpins all of Uber’s successes; the company has staked its reputation on numbers.

Of all of Uber’s numbers, one is particularly important: $90,766. In a late-May post on its blog, Uber cited $90,766 as the median annual income of a driver for UberX in New York City. “UberX driver partners are small business entrepreneurs demonstrating across the country that being a driver is sustainable and profitable,” the company wrote. “In contrast, the nation’s taxi drivers are often below the poverty line … so that wealthy taxi company owners can reap the benefits of drivers having no other option to make a living.” Uber was the heroic disrupter of those taxi companies, and $90,766 was its version of the American dream—proof that contract workers in the so-called sharing economy could do much more than just make ends meet. In recruiting drivers to its platform in New York and around the world, little has been more important than the glimmer of $90,766.

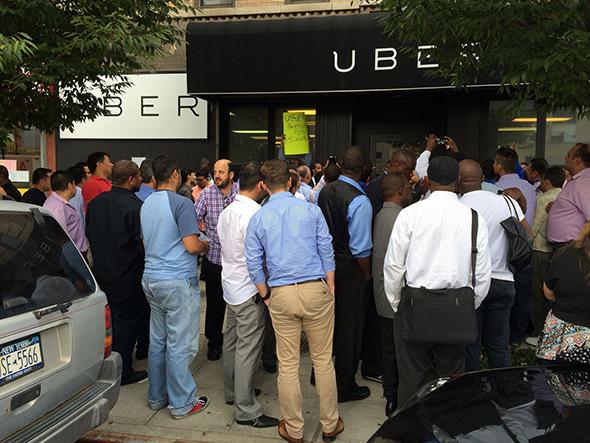

Lately though, as fares have fallen and Uber’s own commissions increased, drivers have grown disillusioned with the company and its promises. From London to San Francisco to New York, they’ve banded together to protest against Uber. The rhetoric they once saw as uplifting now seems deceptive and manipulative. Slowly but surely, Uber drivers are questioning whether Uber’s promises about wages and “small business” opportunities are actually aligned with reality. And in New York, the birthplace of this grass-roots labor movement, $90,766 is starting to flicker out.

When I meet up with UberSUV driver Abdoulrahime Diallo at a Starbucks in Manhattan’s Flatiron District, it’s a Wednesday morning, but he has time to chat. Instead of scouring the busy streets for passengers, he and Jesus Garay, a driver for UberX, have turned off their Uber phones as part of a daylong strike over recent cuts to fares and alleged poor treatment by the company. In London, drivers are doing the same while in San Francisco and Los Angeles they’ve gathered at Uber headquarters to protest. Here in New York, Diallo and Garay are helping to coordinate the strike as organizers of a nascent group called the Uber Drivers Network.

This is the latest in a series of recent protests against Uber. Over the summer, Uber lowered fares by 20 percent in a bid to make its service “cheaper than a New York City taxi.” Drivers, they said, would benefit from increased demand, lower pickup times, and more trips per hour—factors that would more than offset a drop in prices. “They’ll be making more than ever!” the company wrote on its blog. In late September, Uber announced that the experiment had been a success and that it was keeping the lower prices in place. Josh Mohrer, the general manager of Uber in New York City, tweeted on Wednesday that the average Uber driver in the city is netting $25 an hour after commission and sales tax.

Courtesy of Uber Drivers Network NYC’s Facebook page

Drivers, so far, are inclined to disagree. “They say it doesn’t hurt the pocket of the drivers,” Garay says of the 20 percent fare cuts. “It does. Because it’s impossible with those numbers to be in business.”

The way drivers see it, ride volume can only increase so much in response to lower prices. Garay says that on average, a ride takes him 20 minutes from start to finish: five minutes to reach the pickup location, five to wait for the customer, and 10 to drive to the destination. For a trip of that length, Garay says he’ll make $10 or $11. “So if you’re busy, you’re going to make three rides in an hour,” he explains. “That’s $30 an hour. That’s before commission, taxes, the Black Car Fund, before you take off your gas …”

The costs that he’s talking about are ones that all drivers, as independent contractors for Uber and licensees of the city’s Taxi and Limousine Commission, have to pay. New York is among Uber’s biggest markets and it offers those riders three different tiers of service: UberX (the cheapest), UberBlack (the middle), and UberSUV (the most expensive). On each of these fares, Uber takes a commission: 20 percent on UberX, 25 percent on UberBlack, and 28 percent on UberSUV. From that fare, the city also takes a sales tax of 8.875 percent and the Black Car Fund takes a fee of 2.5 percent.

For a driver like Garay, all those deductions mean an initial $30 in fares leaves him with about $21 for the hour. According to statements Garay provided Slate, he made $1,163.30 in fares for 40 hours of work in the week ending Oct. 13. From that, he took home just under $850. In any given week, Garay expects to lose a bit more than $350 to gas, car cleanings, insurance, maintenance, and parking costs. That leaves him with about $480 before income taxes. Effectively, he’s making $12 an hour.

Twelve dollars an hour isn’t terrible. But it’s a far cry from the kind of numbers that Uber advertises to drivers on its platform—the numbers it uses to paint itself as empowering contract workers in the sharing economy. The statements themselves are also confusing. A diagram in Garay’s statement shows he worked 40 hours, but a note below it says his “hours online” were just 32.8. He tells me it doesn’t make sense. The trick is that Uber is referring to two different kinds of hours: those spent online (available on the app) and those spent with actual customers in the car. When drivers think about hours, they think about the first kind—hours spent on the app looking for rides. But when Uber breaks things down, it’s interested in the second—hours shepherding passengers. Uber and its drivers have fundamentally different notions of how drivers’ time and effort should be measured. And as fare cuts have made profit margins slimmer all around, those differences have increasingly led to clashes.

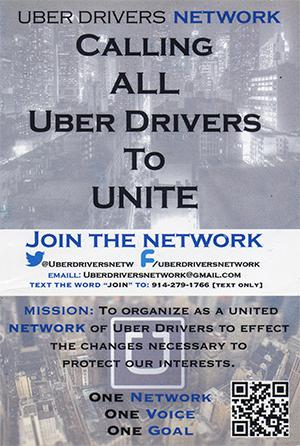

The founding members of the Uber Drivers Network met for the first time in May; in the months since, they’ve recruited others through word of mouth, social media, and printed fliers, and they’ve stirred up a handful of protests and strikes. The New York City branch of their Facebook group has more than 1,500 likes, and they say membership is closer to 2,000, or 20 percent of the city’s roughly 10,000 Uber drivers. (Uber declined to confirm the number of drivers it has in the city, calling it “proprietary.”)

Courtesy of Uber Drivers Network NYC

As the drivers have banded together, a crucial question has emerged: In the sharing economy, in which a company like Uber serves primarily as the middleman between service buyer and service provider, who holds the true power?

Thrown into the race without a clear answer, the three main companies in the field are using one of two strategies to build out their platforms. First, there is Uber’s: cut prices to please the consumer. Lyft, another major player in the ride-sharing game, has operated similarly to Uber; the two are engaged in something of a race to the bottom to draw in customers (and Uber, at least, believes that race will also lead to more fares and more money overall for drivers). The third contestant, Gett, has taken a different approach: raise pay to please the driver. “Drivers are crucial, obviously, to this equation,” says Ron Srebro, CEO of Gett USA. “You have nothing without customers, but you have nothing without drivers.” Two weeks ago, Gett announced that it would pay drivers on its platform a flat rate of $0.70 per minute—an amount it said would double the typical rate for drivers on Uber and Lyft.

So far, Uber is the clear leader in ride-sharing. Its reach is far more vast than that of its competitors, and its funding far greater. Whereas Gett and Lyft still feel like startups, Uber has acquired the air of inevitability associated with a massive corporation. But it remains to be seen which company’s strategy will pay off in the long run. “That’s what’s kind of interesting about this model,” says Wally Hopp, senior associate dean for faculty and research at the University of Michigan’s Ross School of Business. “It’s not clear which of those audiences—the customers or the workers—is most important to you.”

In jockeying to win over consumers in particular, Hopp thinks companies like Uber and Lyft have veered away from their free market principles and artificially deflated fares. “I think there are some underpriced rides out there, meaning you can do it for a little while, maybe burning through some of your venture capital or burning through some of your good will from the drivers,” Hopp says. “Uber is not in a position to let their algorithm work and float prices to the market-clearing level, so they’re actually keeping prices below what the drivers want, in order to gain market share.”

Uber might be leading the race now, but scoring $1.2 billion in funding while trying to fundamentally overturn the age-old taxi industry is a quick way to put a target on your back. So is fielding repeated public accusations of using dirty tactics to sabotage competitors. In Hopp’s estimation, the current jockeying can only last so long. He sees on-demand car services becoming a commodity, with fares and wages competed down to the lowest possible levels. “One provider is going to be viable,” he says, “but two or three or four is not.”

Considering how fast Uber has grown and changed—and the sheer number of people it employs—it doesn’t seem so odd that worker protests were in its future. But Lane Kasselman, Uber’s head of communications for the Americas, isn’t interested in discussing that. “We look at it differently,” he tells me. “Drivers are our customers. They’re the ones that are licensing the software and—fundamentally from Uber—are getting regeneration and marketing, and getting small business tools.

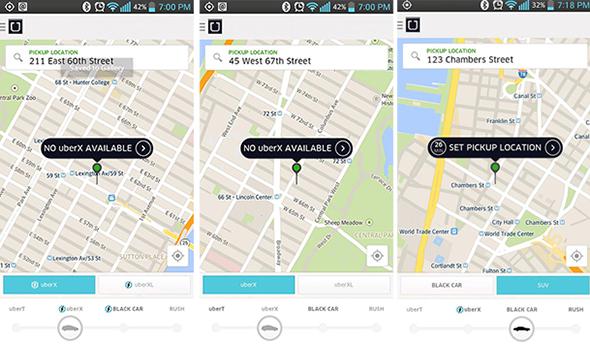

“We’re creating 50,000 new jobs through our platform every month,” Kasselman continues. “Drivers are excited about the economic opportunity that’s happening.” I mention the previous Wednesday’s protest. “There were no protesters in New York, Chicago, or D.C. at our offices, and literally only a handful in L.A. or San Francisco,” he says. “We saw no impact to supply in New York … there was no unusual pricing.” This last claim directly contradicts what the Uber Drivers Network reported on its Facebook page. In a series of enthusiastic posts, organizers shared screenshots of several Manhattan neighborhoods showing 20-plus minute waits for an UberX and some areas where no car was available at all.

Screenshots courtesy of Uber Drivers Network NYC

Kasselman emphasizes that drivers on Uber’s app earn an average of $25.79 per hour in New York after Uber’s commission. He’s not sure if the sales tax is included in the commission or taken separately, and suggests I contact the Taxi and Limousine Commission to ask. (I do; they direct me back to Uber.) I relay to him that Uber drivers say the 20 percent cut to fares is unsustainable, that after commission and tax and fees they’re barely scraping by.

Uber disagrees. Kasselman refers me to the late-May blog post, the one claiming that the median UberX driver in New York City was making an annual income of $90,766. That’s a lot of money. Even in New York City, those earnings alone would put you safely in the top 30 percent of households. I suggest to Kasselman that this figure seems unlikely to still be true, especially since the fare cuts kicked in. He reiterates that lower fares have increased ride volume so that drivers are now making more than ever. That said, even at $25.79, $90,000 is a tough mark to hit. You’d need to work 70 hours a week for 50 weeks a year.

In several months of reporting on Uber, I have yet to come across a single driver earning the equivalent of $90,766 a year. Those I’ve spoken with report that they gross around $1,000 a week after commission and sales tax—but before gas and other expenses—for annual income closer to $50,000. And despite broadcasting the $90,766 figure far and wide, Uber has so far proved unable to produce one driver earning that amount. Even the driver Uber itself put me in touch with, Adam Cosentino, wasn’t working at that level. Instead, he’s putting in 30 or 40 hours a week while he gets his MBA, optimizing for the busiest hours and bringing home between $800 and $1,000 a week. He’s happy with it. He spends about $200 a week on gas and $30 on cleaning. Another $300 toward the car. After commission and whatnot, he’s left with maybe $400 or so for his efforts.

“Adam,” I say, “that’s not a lot of money.”

He considers this for a moment. “Nah, no, it’s not,” Cosentino admits, “but listen, that’s because I’m not putting in the full amount of hours. If you want to work six days a week … most of these guys that are making $2,000 a week are working 60 hours.” I ask him if he knows anyone doing that. “I don’t personally know any of them,” he says, “but I can only tell you from my personal experience. If I were to work for 60 hours a week, I can guarantee that there would be $2,000.”

It’s great for Uber that he believes that, but it’s also odd that these $90,766 drivers are so hard to come by. After all, that’s the median according to Uber’s data, which means that by definition half of its thousands of drivers in New York City should be earning that much or more. And I was desperate to speak with one of these drivers. I wanted to see the true Uber dream. So I asked Kasselman to find me just one. Find me Uber’s unicorn.

Last I heard, they’re still looking.