In the financial world, some shares have new owners every second. Today, much of the buying and selling is done by computers, but many trades still rely on human intuition—the gut feeling of the experienced trader.

“Nobody can predict the market, but traders are expected to,” Richard Taffler, professor of finance at the University of Warwick, said. “This creates anxiety.” Anxiety is just one of the emotions that play an important role in driving financial markets. Understanding what happens in the brains of traders as prices move up and down could possibly tell us something about a market’s future developments.

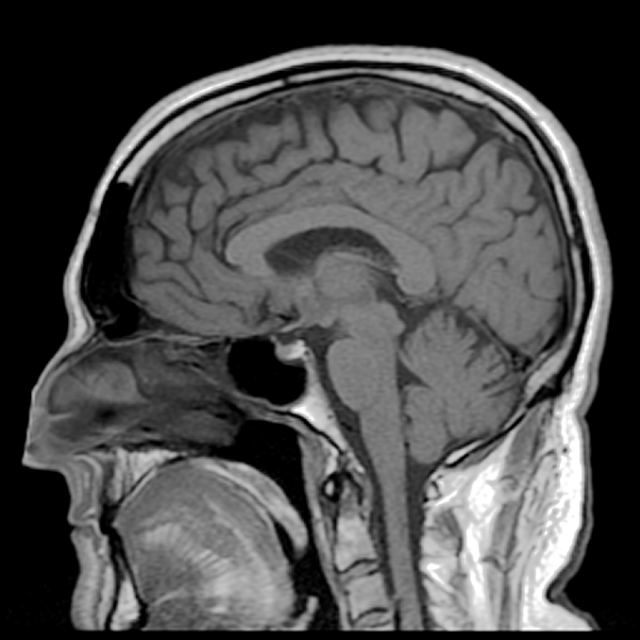

In a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Alec Smith at the California Institute of Technology and his colleagues conducted group-behavior experiments. They had between 11 and 23 students play multiple rounds of a game that simulated a market situation. For every round of the game, three of the participants were inside a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) machine, which identified parts of the brain that have increased or decreased activity during the trading.

The game started with an asset at an arbitrary value. As the market develops over time, the asset’s price increases. The experiment is setup such that a market bubble always forms and then bursts, causing the asset to return to its initial value in a very short time.

Smith and his colleagues found that activity in a brain region called the nucleus accumbens (NA) correlates with the market price—if the price goes up, the NA gets more active. “This brain region was previously associated with emotions, fear, and pleasure,” Smith said. “It makes sense we find this region active.”

In the next step, the researchers compared the activity in the high or low earners, in order to determine if any specific brain activity was associated with trading outcome.

In this game, low earners buy around peak price, while high earners sell their shares around the same time (presumably, to the low earners). The researchers suspected that this behavior might be associated with activity in the anterior insular cortex, located behind the forehead. The insular cortex is active during bodily discomfort—when you feel pain, anxiety, or disgust. The anterior region is also activated by financial risk.

Smith found that, around the time when prices are about to hit the peak (that is, a bubble is starting to form), insular activity increases in high earners but shows no change in low earners.

The upshot is, if you could measure the brain activity underlying certain emotions of a successful trader in a critical market situation, you might be able to predict how prices will change. Of course, even successful traders are often wrong during bubbles, so knowing who to stick in an MRI tube would be a challenge.

Taffler isn’t sure that this approach would translate to the real world. “It is not clear how we get from undergraduate students, in a confined laboratory environment, without a real potential of loss to a real world market situation,” he said.

Instead, the professor proposes that we should observe and learn from behavior and price development in real-world market bubbles to capture the complexity of the market. “It is not clear that you can use the traditional scientific approach to analyze social behavior”, Taffler said.

Smith insists the behavioral game is not too much of an abstraction from reality and we can use it learn about the principles of price bubbles and possibly other cases in which human groups badly judge the value of actions or events. In any case, the next step is probably not to connect every Wall Street trader to an fMRI—fMRI scanners are too expensive, even for bankers' deep pockets.

PNAS, 2014. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1318416111 (About DOIs).

![]() This article originally appeared at The Conversation.

This article originally appeared at The Conversation.

reader comments

31