Testosterone made my voice low. Really low. So low that I am almost impossible to hear in a loud bar or a cacophonous meeting, unless I speak at a ragged near-shout. But when I do talk, people don’t just listen: they lean in. They keep their eyes focused on my mouth, or down at their hands, as if to rid themselves of any distraction beyond my powerful words.

Pretty remarkable for someone who spent 30 years being tolerated (at best) or shunned (at worst) in work environments. Before testosterone, my beardless, androgynous body was troubling, unprofessional. At a corporate job, I was once asked explicitly to not meet with important clients, as the very sight of me might “send the wrong message.”

I was regularly interrupted. At meetings, my voice didn’t prompt people to pause and listen. I never hard-balled a salary negotiation, either. And I wasn’t ever hired, as I was two years ago, for my “potential.”

All this is despite the fact that I have only worked in progressive environments, places where I have heard men reflect on internalized sexism and where women occupy prominent leadership roles.

Therein lies the danger, says Dr. Caroline Simard, senior director of research at Stanford’s Clayman Institute for Gender research. Her team studies implicit bias, “errors in decision making” that result in the thousands of subtle behaviors perpetuated unquestioningly by almost everyone, of every gender, in the workplace. ”Even when we think we can evaluate rationally,” Dr. Simard says, “bias leads us to errors in judgment.”

The sheer reach of implicit bias is troubling, and can even end up baked into our best business practices—like the advice managers get to trust their ”gut” when deciding an employee’s potential (instead of applying predetermined criteria or assessing performance data).

The first time I spoke up in a meeting in my newly low, quiet voice and noticed that sudden, focused attention, I was so uncomfortable that I found myself unable to finish my sentence. I was in Boston, working with a crew of rowdy journalists, in a body that was sprouting hair and muscle and looked, for once, familiarly male to everyone I encountered. It was the most alien I had ever felt.

But the room stayed quiet along with me. It was the order of things: everyone in the room waited, men and women alike, for me to open my mouth.

I am taken more seriously

Though I have freelanced my entire adult life, I began my career in media at 30, as a copy editor at the Boston Phoenix. Within a year, I was an editor, and within three, I was the managing editor of the millennial news outlet, Mic. Five years since I took that lowly copy editing gig, I’m the director of growth and an editor here at Quartz, where I received a promotion before the end of my first year.

That achievement came partly because I figured out my path during that time, like many people in their thirties. I also work hard, and I’m confident that I’m good at my job.

But I also believe that some of my recent success has got to be linked to the way I am treated as a man. Every day, I am rewarded for behavior that I did not previously exhibit, such as standing up for my ideals, pushing back, being fluent in complex power dynamics, and strategically—and visibly—taking credit. When I prove myself, just once, it tends to stick.

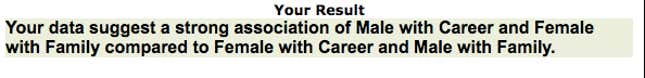

“We assign more credibility and expertise to men,” Dr. Simard says. And by we she means all of us. Harvard researchers designed a test to gauge your personal inclination toward bias, but spoiler alert, you’ll likely do as well as I did:

The problem is so pervasive, it shows up in even the most mundane management endeavor: the performance review. Dr. Simard co-authored a paper in the Harvard Business Review on analysis performed by her and her colleague at Stanford, Shelley Correll, into 200 reviews within the same large technology company. Women were more likely than men (57% to 43%) to receive what the researchers termed “vague praise”—feedback not tied to any actual business outcome (“You had a great year”). Men were more likely to receive praise connected to their actual contribution to the company.

Moreover, feedback for women focused intensely on communication styles, particularly the critique that the employee was ”too aggressive.” The researchers found that 76% of references to being “too aggressive” was found in the women’s reviews, which left only 24% in the men’s.

Feedback may feel like a soft metric, but think about the ramifications. “A performance review has an effect on your leadership brand over time, and even how you see yourself,” Simard says. It affects how you are discussed among senior leadership, and can impact your chances at receiving highly visible “stretch assignments” that tend to lead to the sort of accomplishments that make a career.

In short, it is the way “potential” is often verbalized, to the employee and among the staff. And potential, Dr. Simard says, is “especially fraught for bias.”

People expect more from me

Being competitive and ambitious predates my transition by at least 20 years. I won a Read-a-thon in the sixth grade by plowing through 600 books in a single summer. I was raised by a single mom who taught me to fight for recognition, and then leverage that recognition to prove my worth. She was a physicist who worked for Ted Kennedy right out of grad school, and then was one of the initial women in a leadership role at General Electric. She had a lot of “potential,” and she definitely didn’t count on anyone noticing it without her help.

It’s amazing what believing in someone can do. My sense since my transition is that people want to believe the best of me. I like to think I have justified this belief. I am asked for my opinion near-daily internally and externally, on matters far beyond the realm of my actual job. All of this positive feedback has helped me to become my best, most productive, most creative, most innovative self.

I also have an antenna for the interruptions, the things nearly said, the young person not getting the credit she’s due. I am part of the problem—I know I must be—but I have a policy of asking all those who report to me for their thoughts in every meeting, to try to make room for the quieter among them. Dr. Simard recommends this, and generally “paying attention to the way in which you make decisions.”

“We cannot teach people to police their thoughts,” she says. “What we can do is minimize bias happening.”

I make more money

Once, after my transition, I nervously prepared to ask for a raise. I spoke to several people in similar roles who made significantly more than I did, and I had a stellar list of measurable accomplishments that exceeded my goals. My friend, a woman who had recently come back from maternity leave to her senior-level role and successful negotiated more pay and a four-day work week, gave me the standard advice: To approach my boss rationally and unemotionally, root my ask in my accomplishments, and not feel guilty for asking for what I’m worth. That last one is what got me. I was worried about my boss feeling bamboozled by the ask.

“I think this is your female socialization,” my friend observed wisely.

I think she was right. Repeated studies have found that there is a social cost for women who negotiate pay raises that doesn’t exist for men. (After all that, I walked into the meeting, ready to hardball, and my boss offered me a raise along the lines of what I’d wanted.)

Some researchers believe that hormone therapy activates dormant genes present in you all along, revealing a kind of twin of yourself. I like to think that we all have a male or female version of ourselves, tied up in our genetic make-up. I remember that every time I lobby for a raise on behalf of one of my employees who may not believe she deserves it, or point out the accomplishments of a female colleague that may have gone unnoticed.

Most of us have the bodies we occupy because of luck of the draw. For those of us who have had to fight for them, the process offers startling insights into what helps and hinders us as we move through space; the costs and benefits assigned to us by our culture; the destructive ways our voices can be silenced. And the way they can also be, so suddenly, heard.