Un-du-la-tus as-per-a-tus sounds like an entry in the Hogwarts’ charms, spells and potions book.

“What would that induce?” ponders Gavin Pretor-Pinney, pictured right, founder of the Cloud Appreciation Society. An enchantment, perhaps, bewitching adults into thinking less negatively about clouds and restoring a childlike wonderment that sees them as “beautiful and ethereal”?

In fact undulatus asperatus is the name conjured by Pretor-Pinney, an amateur enthusiast, for an as yet unclassified, intensely wavy and turbulent cloud formation. And if it makes the International Cloud Atlas next November, it will be the first official new classification in 60 years.

A gunmetal sky hangs over the converted barn in rural Somerset where Pretor-Pinney lives and from where he runs the society and its online shop. “Not just grey, see the slight variations in tone,” he traces with a finger. Members of his society – 37,000 and growing – wouldn’t see just a grey sky. They would see stratocumulus.

Members include artists, poets, musicians, but also meteorologists. They share photographs of clouds from around the world of such excellent quality that Pretor-Pinney has stopped reaching for his own camera. “Now I am a bit more Zen-like. If I see a cloud, I just enjoy it and then let it go.”

The society’s manifesto is to overturn the perception clouds are “just something that get in the way”, that cast a shadow when sunbathing on a beach.

“There is such negativity about clouds written in to our language; somebody has a ‘cloud hanging over them’; there’s a ‘cloud on the horizon’. They have become a metaphor for annoying obstructions and obstacles in life,” Pretor-Pinney says.

The society’s mission is to banish “blue-sky thinking”. That the things all around us make life interesting, stimulating, and should not be blocked out, is part of the thinking of this man, who studied philosophy and psychology at Oxford.

But because they are omnipresent we have become blind to clouds, failing to see them as “nature’s poetry”.

If more people looked “aimlessly at the sky”, psychoanalysis bills would be slashed, he believes. Cloud watching “legitimises doing nothing”, and is a perfect antidote to a digital world “where everyone is perpetually expanding their to-do lists”.

Pretor-Pinney, 46, a self-confessed “science nerd” at Westminster school in London, who studied for an MA in graphic design at Central St Martins after leaving Oxford, co-founded The Idler magazine and worked as an art director for various companies, including the Guardian, before becoming an author and cloud enthusiast. His books include the surprise bestseller The Cloudspotter’s Guide, and award-winning The Wavewatcher’s Companion, which claimed the 2011 Royal Society Winton prize for science books, and whose genesis was in a cloudless day spent at the beach.

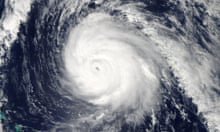

He makes a living serving up serious science in an accessible, fun way, and is invited to lecture worldwide as the corporate world seeks to harness creativity in its work force. In Arizona, he once found himself speaking alongside former US presidents Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton, and rapper Snoop Dogg. Delegates thought he was there to talk about cloud storage, but were soon shouting for “the cloud guy” when the tail end of a hurricane filled the sky with a spectacular rose-tinged cumulus congestus, “like some divine intervention”.

Half of Cloud Appreciation Society members – the group celebrates its 10th anniversary next year – are British. “I think it’s the British mentality around the weather, maybe we have to laugh at it.” The rest are mainly from English-speaking US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, Photographs, art work, music, poems, are all shared on its web forum. So, too, is scientific information, including the debate on clouds and climate change.

For their £7 life membership, each receives a certificate and a badge to wear with pride. “It is a statement that says I am somebody who finds beauty and what is special in the mundane everyday stuff that most people miss,” he says. A celebration of “finding the exotic in the everyday”, he adds.

Pretor-Pinney’s interest was piqued when he took a sabbatical from The Idler and went to Rome. After six months of mainly blue skies and no clouds, he realised he missed them. He was surrounded, too, by baroque churches spilling forth images of clouds everywhere, as “the sofas of the saints”.

Invited by a friend to share his passion at the Port Eliot creative festival in St Germans, Cornwall, he decided to call his speech “the inaugural lecture of The Cloud Appreciation Society”. In the audience was Liz, the woman who became his wife and mother of their two daughters, aged eight and five. “It was quite a good event for me, because I got a wife out of it, and a society out of it,” he jokes.

If identifying and naming a new cloud formation might rate as the pinnacle of cloud-spotting success, Pretor-Pinney finds himself most intrigued by the process required to have a new classification officially accepted. The last addition was in 1951. The official world of clouds, presided over by the World Meteorological Organisation, is bureaucratic. “Ironically, clouds are in constant change, but the world of cloud classification is somewhat rigid,” he says.

Pretor-Pinney first saw images of the dramatic formation he has named when they were sent from Iowa in 2005. Members followed up with more evidence from around the world. “The formations were more dramatic and exaggerated than usual. Undulatus like they were turned up to 11. I began to wonder what would happen if you think there is a case for a new classification.”

A name was needed. Undulatus, meaning wavy, already exists in the cloud lexicon. But how to convey the turbulence he saw? He consulted a Latin-teacher cousin, who turned to Virgil, and came up with asperatus, past participle of aspero – to roughen. Perfect.

News of the possible adoption of this formation by the official cloud community has seen a renaissance of interest. Pre-Christmas sales at the Cloud Appreciation Society’s online shop – mugs, stickers, rotating portable cloud selectors, books, cushions, bedding, baby wear, anything with a cloud inspired design – are up a third on last year. Membership continues to grow.

There are about 80 varieties of clouds classified, with Pretor-Pinney’s favourite probably being lenticularis, which looks like a UFO. Get a few of those stacked one of top of the other and you have the pile d’assiettes, or pile of plates. Another wonder. There is endless entertainment in clouds and their constantly changing shapes.

As for Pretor-Pinney’s philosophy, it can be summed up simply: “Have your head in the clouds to keep your feet on the ground.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion