From silver mine to wet plate

- Published

For the first 150 years or so, silver was an essential ingredient to photography, those little particles that reacted to light to create an image. Photographer Sean Hawkey decided to take his camera to the source and photograph the miners who extract the silver from the earth.

Of course Hawkey did not take a standard 35mm film camera, but lugged a mobile darkroom and laboratory, heavy antique equipment and lights, plus 20kg (3st 2lb) of metal plates for his large-format camera.

His passage through customs was an interesting one as nitric acid and diethyl ether are controlled substances, yet both essential in the production of photographic plates when using the wet collodion process.

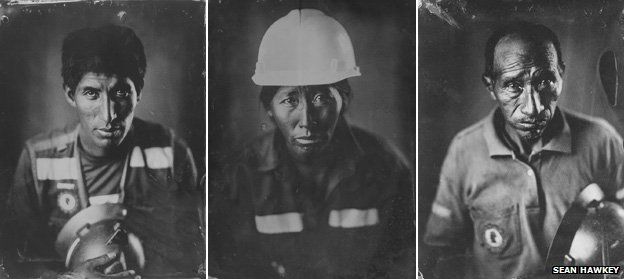

What makes this project so absorbing is that Hawkey's beautiful pictures of miners at the Fairtrade certified Sotrami mine in Peru were made using silver dug out from its depths.

"I went underground with miners, drilling, blasting with dynamite, and disinterring the precious metal," says Hawkey.

"I've worked in construction, demolition and civil engineering, but the mine is the toughest environment I've been in.

"One miner with the same birthday as me told me, 'We're the same age, but I'm older than you. The mine makes you old.'"

Hawkey learnt how to use collodion from John Brewer specifically for this project, noting that its beauty comes from the imperfections, and the fact that so many things can go wrong. It's a far cry from the predictability of working digitally.

He adds: "And I love the stillness. In early photographic images, people are composed and serious, and they had to be because the exposures were really long. So you get some quite profound portraits.

"I feel there's an intense, spiritual quality about the pictures because of the long exposures and required stillness. It's impossible to take a grinning or whooping selfie with collodion - and I'm not challenging anyone to try. I think it's a good thing you can't do it."

Of course the process should only be attempted by anyone with the correct training and safety equipment.

One thing that intrigued me was how the miners reacted to his requests to take their picture in this way.

Hawkey says he felt like a bit of a "berk" as he began to describe his artistic concept to the miners.

"I was afraid of what they'd make of it - they endure an aggressive routine of dynamite, rock-smashing and hauling heavy sacks up 400m ladders.

"I wondered if they'd snort in disdain. But they didn't."

"First of all they were a bit amazed that I'd brought vintage gear and a darkroom with me from England, to their remote mine in the Andes, but when they saw the plates, they were thrilled.

"They all wanted a portrait, they all wanted to see the process, and miners lined up to have their picture taken, and they cheered when the images appeared in the fixer."

It wasn't only miners Hawkey photographed. One night, word having spread of this Englishman taking pictures with an old camera, he found four policemen at the door of his bunk asking about the work.

Initially he was worried he had broken some law but was relieved to find out that they too wanted their picture taken.

"Some of the miners were aware of the great early Peruvian photographer Martin Chambi, who carried a wooden camera around the Andes. That was a useful reference.

"They laughed when they saw me mixing Inca Cola with the developer - the sugar restrains heat-induced fogging.

"And you can see in the pictures, as well as their magnificent faces and hard lives, there's no animosity, they were willing, friendly subjects."

Here is a selection of Sean Hawkey's pictures from Peru.