Computer scientists have uncovered direct evidence that a small but significant percentage of encrypted Web connections are established using forged digital certificates that aren't authorized by the legitimate site owner.

The analysis is important because it's the first to estimate the amount of real-world tampering inflicted on the HTTPS system that millions of sites use to prove their identity and encrypt data traveling to and from end users. Of 3.45 million real-world connections made to Facebook servers using the transport layer security (TLS) or secure sockets layer protocols, 6,845, or about 0.2 percent of them, were established using forged certificates. The vast majority of unauthorized credentials were presented to computers running antivirus programs from companies including Bitdefender, Eset, and others. Commercial firewall and network security appliances were the second most common source of forged certificates.

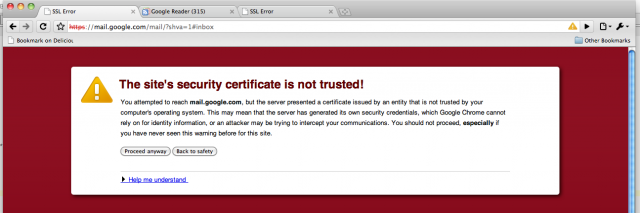

At least one issuer of certificates—IopFailZeroAccessCreate—was generated by a known malware sample that was presented 112 times by users in 45 different countries. The discovery helps to explain bug reports such as this one made to developers of the Chromium browser describing the mysterious inclusion of a TLS certificate on a large number of end users' computers.

Tiny sliver of big pie == many connections

While the forged credentials represent a tiny sliver of the overall TLS traffic, the margin represents a large number of potentially compromised connections when considering the billions of Internet users who in turn each make thousands of connections to Facebook and other large websites on a monthly basis. Similarly, the forged certificates remain concerning even though the majority were issued by security products the researchers presume were intentionally installed by end users.

"One should be wary of professional attackers that might be capable of stealing the private key of the signing certificate from antivirus vendors, which may essentially allow them to spy on the antivirus users (since the antivirus root certificate would be trusted by the client)," the researchers explained. "Hypothetically, governments could also compel antivirus vendors to hand over their signing keys."

More troubling, of course, was the discovery of forged certificates issued by malware and adware programs for purposes of ferreting log-in credentials out of, and injecting banner ads into, encrypted Web traffic. Because the certificates were installed by software that made administer-level changes to the end-user computers, they likely generated few if any error warnings when they were presented.

The academic paper, authored by researchers from Carnegie Mellon University and Facebook, is also notable for introducing a novel way for websites to gauge how many of their visitors used counterfeit certificates when establishing TLS connections. The technique, which relies on Adobe Flash-based code served by the site, could prove especially useful in the aftermath of the so-called Heartbleed bug, which exposed private encryption keys for an estimated 500,000 sites for more than two years. With huge numbers of potentially compromised certificates and no reliable way for any browser—be it Google Chrome or any of the others—to block revoked TLS credentials, the technique could be an effective way for websites to independently measure and prevent attacks on visitors.

reader comments

55