The New York of my imagination, before I came to ♥ the real thing, was a weird amalgam of notions gathered from all over – the Ramones, Rosemary’s Baby, James Thurber, the Velvet Underground, Woody Allen, Diana Vreeland, Taxi Driver, Henry James and Edith Wharton, The New Yorker. But my most seminal images of New York, lodged all the more firmly in my mind for having been subliminally implanted when I was but a wee tot, were sitcom ones.

From That Girl, I learned of the exciting and sweet Manhattan life of an aspiring actress, one who went on dates – and lived in her own apartment! I Love Lucy, familiar as breathing to those d’un certain âge, displayed a life in New York as smooth as silk: your man might be a professional bandleader, but he’d still keep office hours as you whiled the day away, gossiping, visiting, maybe dusting a bit – albeit very decoratively, in an immaculate polka-dotted dress with a big, full skirt and little white pointed collar, the whole surmounted by a complicatedly crenellated hairdo. Which seems ridiculously unrealistic, until you consider that decades later Friends would ask us to believe in a New York where a bunch of sketchily-employed twentysomethings (also ever-decorative, if casually dressed in a faux-hip style) can afford to live, with tremendous ease, in a brace of gloriously spacious apartments in the West Village.

The “idiot box” is not ordinarily considered as a serious didactic tool. Though its primary purpose may be the peddling of soap or cars, even the most lightweight television show shapes and disseminates our most elemental images of society, especially in the minds of the young. Television gives most of us our first glimpse of unfamiliar cities: how they look, and what it means to live there. For suburban or rural kids in the US, television, and in particular the sitcoms that are the first adult shows most American kids are apt to see, first enable us to picture ourselves in the exciting and strange environs of a city.

And we take those pictures with us: the imagined world lighting our way into the real one.

Shiny happy cities holding hands

Sitcoms are shot mostly indoors on standing sets, so the impression of an American city you receive from watching one is necessarily cerebral, detached, made up of talk. You can’t form your own ideas about how the place looks or feels; instead you’re gathering the ideas of others, of the people who are inside, talking.

And laughing. The sitcom is a machine for making viewers relax and unwind after a hard day’s work. It’s meant to slip down as easily and refreshingly, as relaxingly as a before-dinner cocktail, and such controversies as a sitcom may contain are invariably handled in a gentle and intimate way, intended to provoke quiet reflection, rather than the outrage demanded by, say, a cable newscast. The sitcom offers us a cast of lovable scamps, rogues, moms, gentlemen and ladies, darned kids, cranky grandparents, all moving together through the situation. A setup: a punchline. (People! – they’re so crazy, right?)

That means that any American city, seen through the sitcom’s lens, will reveal its friendliest, happiest face, with just enough conflict thrown in to provoke a half-hour’s interest. Not a false face, mind you; for to some extent, surely, what people think of the place and say about it is, in fact, the truth of that place? Just: you’re seeing the place (or to be more exact, the people who live there) in a good mood.

Everywhere, USA

Many, if not most, of the stories in I Love Lucy could have been set in any American city, as if the intent were to communicate the familiarity and homeliness of Manhattan and by this, the shared experience of all Americans, rather than any lofty ideas of urban sophistication or worldliness such as we would eventually see in the New York of Sex and the City and 30 Rock. This bedrock egalitarianism (we’re all the same, deep down) is a key feature of I Love Lucy’s longevity: the Ricardos’ world is one we’ll always be invited into, where Carrie Bradshaw’s will ever be a place that few can afford even to visit. In this way, Seinfeld followed in Lucy’s footsteps: all shared the discovery that if we did not have a Soup Nazi of our own to torment us, in every city neighbourhood there was a local Sushi Nazi, or a Steak or Szechwan or Cocktail Nazi, who’d turned us into craven slaves willing to suffer nearly any humiliation for the sake of their irresistible wares.

In the 1960s, Green Acres addressed America’s rural/urban divide in the person of Oliver Wendell Douglas, a well-to-do lawyer who gives up a glamorous life in New York for his dream of owning a farm near the fictional town of Hooterville. Douglas, played by Eddie Albert, was a wonderfully Mitty-like confection, and Eva Gabor, who played his Hungarian wife Lisa, was the perfect smart/dumb-blonde comic foil. The show was wildly popular, especially with older audiences, but by 1971 a taste for more “relevant” stories had taken hold and Green Acres fell victim to the so-called “rural purge” along with The Beverly Hillbillies, Petticoat Junction, and Mayberry RFD.

Decades later, the citizen of a desperately polarised America can look back at these shows and see quite clearly the value and relevance that the programming executives of the 1970s missed. The bucolic residents of those fictional country towns – Hooterville, Mayberry, Crabwell Corners, Stankwell Falls – were “behind the times” but also lovable and human, and, at least by the end of a goofy half-hour, always found that they got along fine with the city folk, and vice versa. Each group was gently mocked for its foibles. The exact location of these fantasy Everytowns was deliberately left uncertain, because the real intent was to show Americans as inclusive, equal, sharing the same human experiences, and all capable of being friends.

Springfield

The same is true of sitcom suburbia, the fictional towns of Chippewa, Michigan (the Detroit suburb where Freaks and Geeks was set), Point Place, Wisconsin (That 70s Show), Lanford, Illinois (Roseanne), and the unnamed Everytown of The Wonder Years (which was apparently a hybrid of Silver Spring, Maryland and Huntington, Long Island, the creators’ home towns; only the Arnolds’ house number – 516 – is a tiny nod to Long Island’s telephone area code). Again, the indefinite location is a deliberate strategy intended to encourage a feeling of universal familiarity. “The subject was being kids,” Bob Brush, an executive producer of The Wonder Years, told the New York Times. “Everybody felt Wonder Years was set in their home street.” The unreality makes the place seem nearer and more real.

By this reckoning, it is unsurprising that the only sitcom to have succeeded in giving a consistently accurate picture of American life is set in a place so fictional that it is a literal cartoon: the city of Springfield, where the Simpsons live. (There are 38 towns named Springfield in the US.) Furthermore, pitch-perfect accounts are given in The Simpsons of New York and Los Angeles, of Miami and Chicago and Las Vegas. This most sublime of American sitcoms is something like a national religion; it crosses all boundaries of politics, race, class and generation; real places, perhaps, can never appear on a map.

Cincinnati

The feelings of Americans with respect to “rubes” vs. “city slickers” are vastly more complicated than they appear at first blush. WKRP in Cincinnati, for instance, nominally presents Cincinnati, Ohio as a place of exile, the city of last resort. The story: Los Angeles megastar DJ “Johnny Sunshine, Boss Jock”, has been disgraced and fired after saying the word “booger” on air. His career is in ruins, and after many false starts he’s wound up in Cincinnati at WKRP, literally the only station in America willing to give him a job. But then he’s given the chance to convert his program to a classic rock format – and lo, Dr Johnny Fever is born.

Anyone who supposes that Cincinnati was being mocked for its obscurity on the cultural map is missing the key point that Dr. Johnny Fever finds himself for real in Cincinnati, here portrayed as a little-known place full of strange, wonderful people, hidden potentialities and charm, if you’ll only give it a chance. (A verdict, by the bye, that jibes exactly with my own experience of Ohio cities.) The show became wildly popular in syndication, and is said to have been the most profitable show ever for MTM Enterprises – “more than The Mary Tyler Moore Show, more than Hill Street Blues,” according to Tim Reid, who played DJ Venus Flytrap on the show. I like knowing that all of America is so fond of that fun-loving community of kindly Midwestern wackos.

Queens

The “relevance” that TV studio execs pursued in the 1970s was valuable in a new way; sitcoms began to offer a new kind of moral instruction, one particularly influenced by the civil rights movement and the fashion for protest. All in the Family was set in Queens, a working-class New York City borough where the trains rattle along above-ground and guys hang around on the sofa watching television. The show took on highly fraught questions of racism and bigotry, gay rights and abortion; though it was based on the smash UK series Till Death Do Us Part, All in the Family was American from stem to stern.

Those were troubled times! Recession times. New York’s affluent residents had all fled to distant suburbs; crime was spiraling ever-higher. Instead of the candy-colored dream world of That Girl, Archie Bunker’s New York was full of danger, poverty and conflict. And a lot of that vision was true. It was the outer boroughs of Archie Bunker’s New York that I first visited myself in the mid-1980s – Greenpoint, in Brooklyn, my first sight of which was a car on fire. Maybe thinking seriously about these things together on television helped spark needed changes, even in the context of a show built for laughs.

Washington, DC

Washington, DC is curiously absent from the sitcom pantheon, perhaps because the sad juxtaposition of the nation’s glittering capital, residing as it does in the centre of one of the country’s poorest regions, is a real antidote to levity. We have had only one really successful Washington, DC sitcom in recent years (The West Wing, for all its dry comedy, being more a dramatic series): Veep, created by Armando Iannucci, the genius behind The Thick of It and In the Loop. For all its brilliance, though, Veep does not succeed in skewering the idiocy of Washington nearly as well as Murphy Brown did in the 90s—so well, in fact, that then-Vice President Dan Quayle saw fit to scold the fictional character Brown (for having chosen to “birth a child alone”) during a real-life campaign appearance in San Francisco. The footage of Quayle was seized upon with glee by the producers of the show, who lost no time in arranging for Murphy to retaliate by having a truckload of potatoes dumped in front of Quayle’s house (a reference to the vice-president’s famous inability to spell the word “potato”.) Was this a fair picture of the real Washington? Oh, you betcha.

Los Angeles

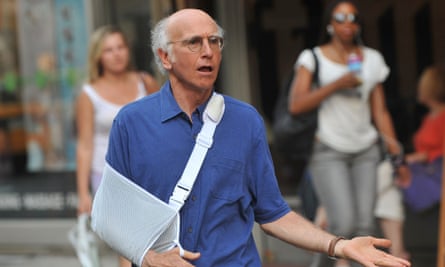

Los Angeles demands to be photographed outside, which is why sitcoms have recently begun to give a far more compelling picture of our city (though I make an exception for I Love Lucy’s series of Hollywood episodes, with their thrilling cameos set in then-famous hot spots like The Brown Derby restaurant.) Arrested Development is perhaps the most truthful of the lot, with its brightness, its foolhardily irrepressible optimism, its surreality and its weird mixture of canniness and cluelessness; Curb Your Enthusiasm is an accurate portrait of Hollywood neurosis, though it is far more a portrait of a man than of a place. Party Down might be the best portrait of what life is like for a lot of Angelenos; because it is a city of freelancers, your friends seem always on the verge of cataclysmic success or failure, half of them flailing and half prospering at any given time.

But the sitcom that evokes Los Angeles most powerfully for me was, paradoxically, not set here. The Cosby Show is set in Brooklyn Heights, at the opposite end of the country. The show’s concept of city life in Brooklyn, and the diversity and safety and prosperity and hopefulness in it, helped to heal my Los Angeles in one of its darkest moments. It provided us the ideal of an American city, not yet a real place, but a city made up of the real ideas and hopes we had (and have) for how things should be, and might yet come to be.

The show starred Bill Cosby as the gynecologist Heathcliff Huxtable and Phylicia Rashād as his wife Clair, a lawyer, along with their five children, Sondra, Denise, Theo, Vanessa and Rudy. Dr Huxtable’s worst vice (aside from what today would be seen as an unacceptable misogyny, I think) is that he is always trying to eat junk food. He can be obnoxious but is mainly goofy and playful, often the butt of jokes. The Huxtable family’s troubles are relatively mild. It doesn’t matter a bit that this family is black. They are just a regular family, basically happy, who live in a fine, comfortable house, and the parents are in love.

Again, the setting is carefully chosen. Brooklyn Heights: Not pretentious and sleek, like Manhattan. But not gritty and working class like Queens. At that time, it was the home of people like Norman Mailer, or Paul Auster, whom one might imagine to be as comfortably at home here as in Greenwich Village, or the Columbia campus on the upper west side. It produced a vision of city life that was simultaneously cosmopolitan and egalitarian.

The Cosby Show’s last episode had been set to air during the Los Angeles riots of 1992; days of violence had been sparked by the outrageous acquittal of four policemen in the beating of a black man, Rodney King. It seemed that half the city was on fire, the very sky a bloody orange, the colour of a hellscape out of Hieronymous Bosch. The only thing on television for days had been terrified news coverage, ceaseless helicopter footage of burning buildings and video of half-crazed looters. But Mayor Tom Bradley worked behind the scenes to ensure that the final episode of The Cosby Show would be aired, as scheduled, in hopes that this much-loved, gently funny, ordinary family would restore a little sanity to Los Angeles.

I’ve never doubted that this strategy worked, at least a little bit. The fantasy, again, easing a path into the real.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion