Part 1 in the “How is That Sustainable?” Series

“Paper or plastic?” This was the question you always used to get once you’d made it through the checkout line to the grocery store register (at least when I was growing up). Ever since about 2005, however, it seemed like it was becoming increasingly rare to get that choice. All the major grocery stores seem to be going to disposable plastic bags by default. Me, I’ve always been a paper bag guy (I’ve since tried to be a reusable bag guy, but I’m not particularly good about remembering to take my bags with me). So I was pleasantly surprised a couple years ago, when I was in a grocery store in downtown Portland, Oregon, and the clerks didn’t even ask whether I wanted paper or plastic, but just deposited my items in a paper bag and sent me on my way. I was pleased at the time, but I later learned that Portland had approved a city-wide initiative to ban disposable plastic bags in grocery stores, in an effort to make Portland a greener city. Now I’m not a fan of disposable plastic bags, and I’ll support any city in its efforts to go greener. But it got me thinking. How do we know paper bags are more sustainable than plastic bags?

Sometimes, it’s easy to tell that you are going greener. The impacts of some sustainability choices are clear and easy to measure. If you combine all your errands into one trip, you use less gas and put less mileage on your car. Simple as that. Sometimes though, it’s very difficult to decide whether You’ve made a choice that is resulting in reduced waste or more responsible use of resources. This is particularly true when you make a green decision that focuses on purchasing a new product or investing in a new service, rather than a decision that just requires you to make a change in your behavior. A hybrid car gets great gas mileage of course, but a hybrid car also needs specialized battery components, which require the mining and processing of nickel, copper, and various rare earth metals. This costs energy and manpower, and has consequences for the mine’s local environment. Some of the metals and other components will have to be shipped across the oceans to the manufacturing facility (or maybe several times to different facilities). This drives the carbon footprint of the hybrid up. How do we know whether it’s greener in the long run to put hybrid cars into production? How would a short-term reliance on hybrid cars compare to putting more diesel cars on the road? How would it compare to fast-tracking purely electric car production? These are complex sustainability questions, and we can’t answer any of them without a clear strategy and well-defined tools to compare the environmental consequences of manufacturing and disposing of used up products.

Environmental Implications: Cradle to Grave

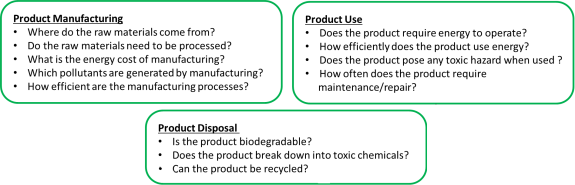

Understanding a product’s overall environmental cost requires understanding where the raw materials to make the product come from, how the product is made, how much waste the manufacturing process generates, how the product will be used, and how the product will be disposed of when its useful lifetime is over. This cradle to grave approach to product analysis is called a life cycle assessment. Without understanding the entire history of the product, there is a chance that when we try to make it greener, we will really just substitute one set of negative environmental consequences for another. Ideally, we would like to do better, and make the biggest green step forward we possibly can.

To understand how a life cycle assessment works, let’s go back to our simple example: paper vs plastic bags. First, we need a sense of what people think about shopping bags and sustainability. People commonly think of three options for shopping bags: paper bags, disposable plastic bags, and reusable cloth bags. If I came up to you on the street and asked you which of the three bag choices you felt was the most “sustainable” choice, you might rank the reusable bag first, followed by paper, and you might say that using disposable plastic bags is the least sustainable choice. You might argue that plastic bags are unsustainable for any number of reasons: plastic is slow to break down when it ends up in the environment, plastic products are often swallowed by birds and other animals with fatal consequences, and the ultimate source for plastic feed stocks is petroleum. Personally, that’s how I would have ranked the three bag choices not long ago. But notice, when we rank the “greenness” of our bags in this way, we are focusing primarily of the fate of our bags in the environment, and that leaves us with a missing piece: we haven’t considered how our three types of bags are made.

The Environmental Cost of Bag Production

Plastic bags are made out of polymers that come from petroleum feed stocks or natural gas. Although petroleum is a natural resource that cannot be replenished on a human time scale, our society has become very adept at making plastics from petroleum products with reasonable efficiency. While high temperatures (hence, a lot of energy) are required to convert the feed stocks to common starting materials like propylene and ethylene, the use of catalysts in industrial plastic manufacturing ensures that these starting materials can be made into polymers (and subsequently, into bags) with good efficiency.

In contrast, paper products are manufactured using a long string of energy-intensive manufacturing methods. In addition to cutting down and milling trees to make the raw materials for modern paper, paper processing is an energy intensive and fairly polluting process. To make paper, the timber must be de-barked and chipped, then, the remaining material must be pulped and refined before the paper making ever truly begins. In addition (as anyone who has ever been by a paper mill knows) paper production smells unpleasant, and produces a variety of pollutants, including dimethyl sulfide and methanol.

And what about reusable cloth bags? While cotton can be grown, and then spun into bags, large-scale cotton agriculture typically occurs on arid land, requiring a large amounts of water for irrigation. Furthermore, the use of pesticides significantly increases the carbon footprint and pollution associated with growing cotton and making cotton products.

Quantifying Environmental Costs and Hazards

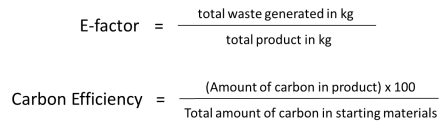

So far, we identified several ways in which the manufacturing of all three bag choices can have significant negative consequences for the environment, but in order to make an informed green decision, we need to be able to compare their environmental consequences by the numbers. Not surprisingly, environmental scientists have agreed on a variety of ways to measure the environmental impact of different manufacturing processes. We call these sustainability metrics. One common metric used to assess how efficiently a product is manufactured is called the E-Factor. The E-factor is a pretty simple calculation. It is a measure of the total amount of wasted materials a manufacturing process generates relative to the total amount of product the process generates. Other metrics (such as carbon efficiency) can be used to assess what percentage of petroleum feed stocks are successfully incorporated into plastic bags or pharmaceuticals.

End Game: The Big Picture for Bags

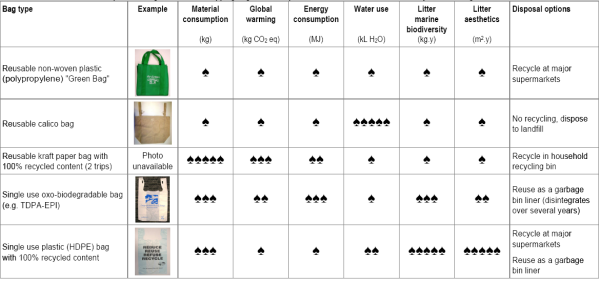

To decide which of the bag choices is greenest, we next take metrics like these and compare them across products over the course of the products’ lifetime (from acquiring the raw materials to sending the used bags to a land fill). Recently, government agencies in many different countries have commissioned life cycle assessments of different products ranging from SUVs to shopping bags in order to to make sustainability policy.

For instance, in 2007, the Australian government commissioned a life cycle assessment to settle our “bagging technology” problem. This life cycle assessment found that bags made from plastic have a lower carbon footprint (less energy input, fewer green house gases out) than bags made from paper or cloth.

Does this mean that Portland and other cities are wrong to ban disposable plastic bags? Of course not! The environmental consequences of improperly disposed plastic bags and bottles can still be devastating, and this is primarily what these cities are trying to avoid. So what can we do to merge low carbon footprint manufacturing with minimizing plastic waste?

It seems a compromise is in order, and many of you will have spotted the solution already. A reusable grocery bag made from recycled plastic has a low carbon footprint, and potentially never needs to be thrown away. Not surprisingly, the 2007 life cycle assessment found that reusable bags made from recycled plastic were the greenest option across the board.

The bag problem is relatively simple, and many of us already knew the answer before we started this discussion, but it is a good example of how you have to look deeply at a product’s many environmental impacts in order to judge its sustainability.

Not surprisingly, scientists often face the same problems when they want to decide whether the use of a single chemical or the development of a whole new type of technology will have a positive or negative impact on human society and environmental health. Relatively young technology fields, like nanotechnology, are in a particularly interesting position right now because our society has a chance to use the principles of sustainability to guide their development from the very beginning. As a result, nanotechnology has an opportunity to become one of the first modern green production industries. Next time, I will explain how the principles of sustainability can be applied to not only the design of engineered nanoparticles, but also to their synthesis and production. We will also take a brief look at Green Chemistry, the philosophy by which chemists develop chemicals and chemical reactions that maximize societal benefit, while minimizing environmental harm.

Acknowledgement: Shout out here to a former professor of mine at Oregon (Dave Tyler), who got many of us former students thinking about life cycles assessments and their relationship to sustainability.

Some more thoughts on paper versus plastic from the American Chemical Society

http://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/education/resources/highschool/chemmatters/past-issues/archive-2012-2013/the-big-bag-battle.html

Huh, I have a variety of reusable bags that I often leave in the back of my car! How does that fit in?

Well, if you were to go back in time and get reusable bags it would seem recycled plastic bags are your best bet. But, given that you already have a wide variety of bags, going out and getting new reusable bags is definitely not the way to go. Using what you already have is the way to go, since the resources have already been put into fabricating it. Awesome question!

Nice post.

Thanks for reading! 🙂