“One thing is for sure,” declared an influential American critic and record industry analyst, Bob Lefsetz, in a recent post on the topic of streaming music. “One service will dominate, it’s where we’ll all go, because we want to share, we don’t want to be left out.”

Music is now undeniably an internet industry—more than 70% of the music consumed in the first six months of the year in the US was either downloaded or streamed, according to Nielsen SoundScan’s latest numbers. And internet industries tend to be winner-takes-all markets. Think Google in search, YouTube in online video, or Facebook in social media.

But that kind of dominance takes time to emerge, and streaming music has yet to reach that point. Many players compete for ears (and wallets): from the original, pure-play internet music services like Pandora and Spotify, to offshoots of radio, like Clear Channel’s iHeart Radio, to new services from the biggest companies in tech—Apple, Google and Amazon.

So will one service eventually dominate streaming music as Lefsetz expects? Or will it remain fragmented? If there is going to be a winner, who will it be, and what will decide the race?

The streaming landscape

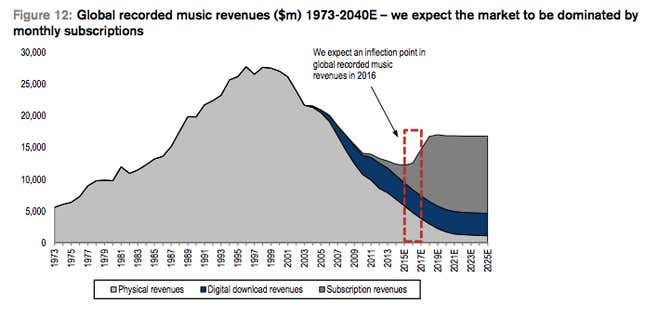

With the exception of vinyl records, which are undergoing a surprising renaissance, online streaming is about the only part of the recorded music business that is growing at the moment. And growing it is. According to Nielsen, on-demand audio streaming revenue in the US was up 52% in the first six months of the year, while digital track downloads were down 13% and CD sales slumped nearly 20%.

But it’s important to distinguish between “on-demand” streaming services (like Spotify) and internet radio services (like Pandora). They have different cost bases and are aimed at different markets.

On-demand services are, broadly speaking, the audio equivalent of Netflix, effectively designed to replace your CD or iTunes library. They allow users to choose individual songs and create their own playlists. They typically have a free, ad-supported version, and a subscription version without ads that allows for offline listening. With 10 million paid-up subscribers, Spotify is the biggest player in this camp. Other prominent ones include Rdio, Deezer, and Rhapsody.

Internet radio services are subtly different. Typically, you can choose an artist or genre to generate an automated “radio station” (and tailor that station by endorsing or rejecting songs that appear), but not choose individual songs to listen to. The biggest of these services is Pandora Media, which had 77 million users at last count. Slacker and TuneIn Radio are others. Spotify also also recently launched a radio-style service, but it is not its core business.

Where Spotify is effectively targeting the market for music ownership—i.e., albums and the like—which was worth roughly $14 billion globally last year (about $8 billion for physical sales and $6 billion for downloads), Pandora is setting its sights on the $16 billion advertisers will allocate this year to old-fashioned broadcast radio.

A pawn in a bigger game

However, streaming music is about to become a pawn in a high-stakes chess match involving the true titans of the tech world. For these firms, the music business isn’t an end in itself, but just one piece in their battle to control the future of the internet.

Apple agreed to spend $3 billion earlier this year on Beats Electronics, at least in part for its streaming music platform (which is mainly on-demand, but has also been described as a Spotify-Pandora hybrid). Google recently bought Songza, a human curation service for music that some believe could threaten Pandora. Google’s YouTube—which you might not think of as a music service, but is easily the biggest site for on-demand streaming of music videos—is also reportedly on the brink of launching a new subscription-based, audio-focused product. Finally, Amazon also recently launched its own streaming product, Amazon Prime Music,to lukewarm reviews. Like its streaming video service, Prime Music is free to anyone who subscribes to Amazon’s premium home delivery service.

These companies might not have the music-first culture that Spotify and Pandora have—although Apple now has Beats co-founder Jimmy Iovine, the ultimate music industry insider, on its books. But they do have some have tremendous advantages: namely, very deep pockets and very little pressure from investors to make money out of music.

“Streaming music, it’s kind of like the moon race, everybody wants to get there first,” says Casey Rae, an adjunct professor at the University of Georgetown and a vice-president of the Future of Music Coalition, an advocacy group for musicians. “It seems like an open contest, but it’s really not.” The winner, Rae told Quartz, ”is probably going to be a company that has other properties, that doesn’t need to depend on the streaming platform itself.”

Not a great business… yet

These firms’ deep pockets will be important, because while consumers are clearly warming to music streaming, nobody has been able to make any money out of it. Not yet at least.

This basically comes down to the costs of content. Consider Pandora, the biggest service of any kind in terms of the number of users. It also happens to be the most transparent, because it’s publicly listed and not hidden within the operations of a bigger conglomerate.

Because it’s a radio service (albeit an internet one) Pandora can, in the US, secure access to the content it needs by buying blanket licenses. The prices for these are set by the government (or if need be, by the courts)—just like for old fashioned broadcast radio stations.

Also because it’s a radio service, where listening is passive, Pandora can also maintain a much smaller music library than on-demand services: It has about 1 million songs in its library, to Spotify’s 20 million plus.

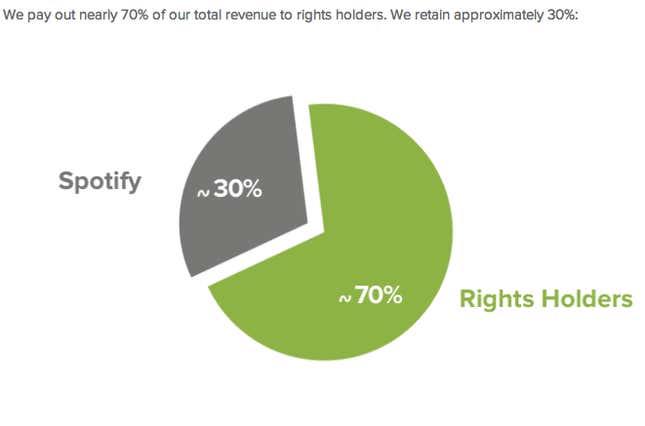

Spotify, by contrast, needs to negotiate directly with content owners (record labels and publishers) and maintain a huge library to satisfy all of its users’ different tastes, even though a large proportion of those songs are apparently never played. So its royalty costs are fixed at a high proportion of its revenues.

Ultimately, this means Pandora has a much leaner cost base than other services do. It paid out around 50% of its revenue in royalties last year. For Spotify, that figure is closer to 70%.

And yet, Pandora is still not really making money. Since its IPO in mid-2011, the company has eked out a quarterly profit just twice (Wall Street is expecting another small profit when it reports earnings on Thursday, July 24). Over the last two financial years it has racked up more than $75 million in losses. And despite these losses, content owners (record labels and publishing companies), perhaps envious of its growing user base and elevated share price, have been aggressively trying to squeeze more out of it in royalties. For some, this offers evidence of structural flaws in the Pandora business model.

Others are convinced Pandora has a bright future. After all, plenty of young, fast-growing companies have lost money early on. Wedbush Securities analyst Michael Pachter argues that Pandora has a clear path to profitability: It pays most of its royalty costs on a per-stream basis, and so it can turn up the profits by simply increasing the number of ads it plays each hour, which would both generate more revenue and slightly reduce its royalty costs (because it’s playing more ads and slightly fewer songs overall).

Pandora could also use the information it has about its listeners to target them with ads specific to them, Pachter says. In theory, this should let it charge more for its ads than broadcast radio stations do. ”Pandora’s leverage is not from exploiting the content guys, its from exploiting the advertising,” Pachter tells Quartz. “Old guys listen to Eric Clapton, they’re more likely to buy Viagra. They [Pandora] know that and they actually know who’s listening to what. Obviously they shouldn’t think old guys listen to Katy Perry and run a Viagra ad during that.”

Pandora has for a while now been tracking its users’ tastes to try and predict which ads would suit them. It has already launched targeted political advertising. (As the Wall Street Journal covered this news, “Pandora Thinks It Knows If You Are a Republican.”) So, during the upcoming US congressional midterm elections, listeners of country music might start to hear more Republican-themed ads, while listeners of classical music might hear ads for Democratic candidates. Evidently, investors think it could use the same method for corporate advertisers.

Spotify’s predicament

But if even Pandora’s ability to generate sustainable profits is still up for debate, then what about Spotify, given its even higher content costs?

On-demand music companies like Spotify have a particular handicap: They can’t get economies of scale. “It’s unique in the media business,” Piper Jaffray analyst James March says. ”In every other media business I cover, if you sell more tickets, or get higher ratings, the operating leverage is massive, you don’t pay more for the TV show or movie. But in streaming music the more popular they get, the more royalties they pay.”

Spotify could choose to build out its internet radio offering, but it’s already playing catch up to Pandora in that business. It generates the overwhelming bulk of its revenue from subscriptions, and seems committed to building its business on convincing people to pay for music.

Unlike Apple or Google, Spotify doesn’t have a massive cash pile to fall back on, or a cross-subsidy from a booming device or search advertising business to protect it. It needs to stand on its own two feet, and quickly. Signs it is heading for an IPO have been in the air all year. The company last raised money at a valuation of about $4 billion. Whether it can achieve the kind of windfall needed to satisfy its investors through an IPO remains an open question.

The company could also pursue a trade sale. The Wall Street Journal (paywall) this week reported that Google had considered buying Spotify “late last year”, although ReCode’s Kara Swisher forcefully refuted the Journal’s report. Mark Zuckerberg is a self-confessed fan of Spotify, and Facebook is about the only giant tech company that hasn’t moved into music, though there have been no reports that it’s considering this either.

And Spotify founder Daniel Ek appears reluctant, at least in public, to countenance an acquisition by a tech giant. “I think it would be a terrible decision for music to be a loss leader for other businesses,” he told Businessweek earlier this year.

The future of music has arrived… in Sweden

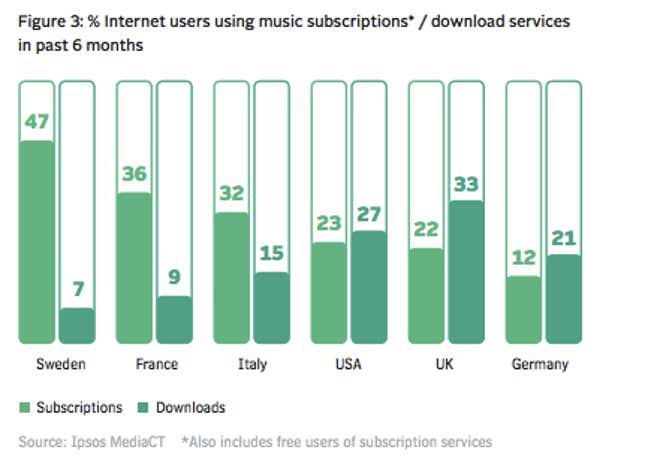

That said, Spotify has reportedly been profitable in its home market of Sweden for years, where streaming music is more common than just about everywhere else.

The company reportedly counts 15% of all Swedes as users, and accounts for 70% of music industry revenue in the country. This also means it has, in theory, more power with content owners there than in say, the US, which would allow it to negotiate cheaper royalty deals.

Spotify is also expanding into big, populous markets, where for copyright reasons, the likes of Pandora can’t go. It launched in Brazil earlier this year, and is expected to enter Russia as soon as this fall. The hope is, if it grows big enough, that the money left over after royalty costs are paid will be enough to keep its investors satisfied.

The elephants in the room

A clearer picture of what Apple and Google are trying to achieve in streaming music should emerge in coming months. But Rae, of the Future of Music Coalition, says that the odds are already stacked in their favor, and not just because they can absorb the high costs of royalties. The standalone services “are the services that are the most vulnerable, because they’ve got licensing costs and you also have got ISPs trying to put caps on users and the whole net neutrality issue,” he explains.

What this means is that, owing to changes in US regulation, content companies may soon be forced to pay internet service providers extra to stream audio and video content to users without annoying time lags. That would put even more pressure on their margins.

If so, the streaming music business (or at least the on-demand form) may well be destined to become a loss-leader for other, more lucrative business activities, Rae says. And it wouldn’t be the first time music has been used this way. Rae points out that in the days of CDs, retail electronics chains like Best Buy sold albums at a discount to get customers in the door so they would buy cameras and music players.

The tech giants already do something similar. Apple’s iTunes store, through which it sells albums for download, was for a long time a break-even business, designed to get people to buy iPods and iPhones, where the real profits lay; a streaming service will further serve that goal. Google tries to get people to use its services as much as possible so it can show them contextual ads. For Amazon, streaming music is just one more way to convince you to pay $100 a year for Prime, a way to lock customers into using Amazon for just about any product they buy.

Active vs passive listening

The future of streaming also depends at least in part on whether people prefer to choose their own music (the Spotify model) or have choices made for them (the Pandora model). Back in the days of vinyl records and bakelite radio sets, everyone had a mix of both. Will it be the same in the internet era? Lefsetz, the industry analyst, thinks not. He wrote in his recent post that “we live in an on-demand world,” and so Pandora’s strength will diminish, though it will survive in some form. ”There’s a market” for passive listening, he added, “[b]ut not run by algorithms, but people”—i.e., by radio stations, both traditional terrestrial ones, and digital ones, like SiriusXM.

That still remains to be seen, of course. And maybe Pandora’s Music Genome Project, which the company describes as “the most sophisticated taxonomy of musical information ever collected,” and involves more than a decade’s worth of analysis and classification of music by a team of trained musicologists, will turn out to have some value of its own as a piece of intellectual property, even if the radio-streaming model doesn’t.

And the winner is…

Nobody knows for sure. But if streaming can continue growing and reach Swedish levels, the music business might not be doomed after all. Last year, Sweden’s recorded music market grew for at least the second straight year, driven by streaming. Consumers there are abandoning piracy and paying for music, now that there is a simple, transparent and cheap way to do so.

Credit Suisse recently forecast that the global music market would, after more than a decade and a half decline, return to growth in 2015, when streaming services hit a 20% penetration rate in the 10 biggest music markets (see chart below). The annual cost of a streaming subscription (about $120 for Spotfiy, $100 for Beats) is well above what the average consumer spends on music, $50 a year. If streaming goes mainstream, a lot of people could be spending more on music than ever before.