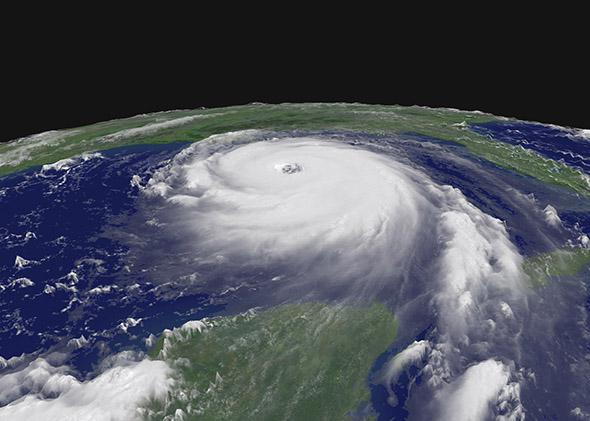

If you were paying attention to the news earlier this month, you might have seen stories about a new study claiming that hurricanes with female names cause more deaths than hurricanes with male names. The researchers speculated that people underestimate the strength of female-name storms and don’t take proper precautions because they associate femininity with weakness. People of the Internet were quick to cite the findings as an example of sexism. Ironically, most of the headlines reporting the story played to the same stereotypes that are supposedly behind the hurricane deaths. “No fury like a woman storm,” reported New Statesman. CNN, for whatever reason, chose to infantilize the storms, calling them “girl hurricanes.”

More skeptical journalists, scientists, and bloggers were quick to point out glaring flaws in the study. Some dissected the study’s methods, Slate re-ran analyses, and others drew up their own models. People dug deep, and the verdict was clear: The study’s data analyses may not have been accurate, and its conclusions were overblown.

However, well after the study had been debunked, Nicholas Kristof bought into the authors’ conclusion and reported it in his New York Times column last week with no mention of the controversy. He even added embellishments not supported by the study, such as asserting the causality between implicit beliefs and action. Kristof wrote:

Americans expect male hurricanes to be violent and deadly, but they mistake female hurricanes as dainty or wimpish and don’t take adequate precautions.

Even aside from the questionable nature of the study, none of this can be deduced from the paper. Participants were not asked about their expectations about the violence or daintiness of storms. And this correlational research has no way of showing that failure to take adequate precautions is what causes people to lose their lives in dangerous storms. (Not to mention that it’s hard to say whether undergraduates’ responses about whether they would evacuate for a hypothetical hurricane has any relationship to what people in hurricane warning zones do in real life.)

Kristof isn’t the only one to engage in bad social science reporting, and last week was quite a week for it. Too many writers love stories with a familiar narrative, even if that narrative is based on shoddy science. Here’s a treasured trope: If only everyone had stable families, all our problems would go away. Last week, in another spectacular misrepresentation of gender research, W. Bradford Wilcox and Robin Fretwell Wilson preached the bad science gospel with an article in the Washington Post initially titled, “One way to end violence against women? Stop taking lovers and get married.” The second sentence was later edited to the less-controversial reply: “Married dads.” But the article’s representation of the research remained twisted.

Researchers, journalists, and readers alike should already know the No. 1 rule of social science: Correlation does not imply causation. There are myriad reasons being married could be correlated with lower rates of abuse, including socio-economic status or likelihood to report crimes. Wilcox and Wilson acknowledge some of these in their article, yet they still encourage married women to “feel safer” and “lift a glass to dear old dad.” They fail to make it clear that getting married or growing up in a home with married heterosexual parents (as if you choose your family circumstances) will not magically safeguard you from violent men. The way to end violence against women is for men to stop abusing women, not for women to get married.

Time did its part in reinforcing gender stereotypes last week with this sage advice: “Ladies can boost their attractiveness by chuckling a bit more. And guys, you can garner more attention by learning how to make women laugh.” Research about human attraction tends to make sweeping claims. This finding may be true for a specific group of study participants (most likely heterosexual college students, given the logistics of most of social science research), but that doesn’t make it a universal human truth. There are plenty of men—in this study and in real life—who think women who tell jokes are attractive, or women who like men who laugh at their jokes. But it’s simpler to stick to the tired image of a charming, witty man and a woman who affirms him, so that’s what we get here. This advice is great for you if your primary objective in life as a woman is to boost your attractiveness to men who like to have their egos stroked, but for humans seeking real, complex relationships, this advice won’t get you very far. (And of course this advice ignores homosexual or transgender relationships.)

These stories are more than just annoying—they have real-world effects. By reinforcing gender stereotypes and roles, the media affects people’s perception of women. Study after study has shown that pre-teens and teens learn about gender and sex from the media, and adults, too, subconsciously take those messages to heart. Gender stereotypes disrupt girls’ behavior on social media sites, limit women’s perceived possible career paths, and bias women’s chances of winning an election.

Stereotypes also can negatively affect women’s daily behavior. One of the most pernicious effects is called “stereotype threat.” When faced with stereotyped assumptions, women or minorities fear they will confirm a stereotype and end up actually performing worse. In a classic study, women performed worse on a math test if they were told the test was meant to show gender differences. Other studies have shown that stereotype threat can cause women to do worse in sports or even driving.

The New York Times, Washington Post, and Time are behemoths in publishing. They have millions of readers. With that comes the potential to misinform millions of people. Writers have a responsibility to understand the work they’re covering and to investigate the discussion around it. In the case of the hurricane study, nearly every other media site reporting this story has mentioned the controversy in its piece or has edited or appended an update to the original article. You’d think a columnist for the New York Times would have the foresight to do some light Googling before reporting a week-old story. Writers, we need to stay vigilant and look beyond the easy gender narratives. Readers deserve better.