Why Are There So Many Women in Public Relations?

The field is nearly two-thirds female. Is it because of a lack of better options—or is it, in fact, the best possible option?

About a decade ago, Adriana Sol was helping design ads in Miami Beach when she realized the advertising trade’s nit-pickiness was slowly draining her energy.

“Everything was in the details,” she told me recently. Every conversation seemed to involve “having the clients tell me that their logo needed to be a quarter of a shade less green.”

She wanted something with more freedom and creativity. In 2005, she applied for a public relations position with Max Borges, a tech-focused agency, and got the job. Within three weeks, she was flown to a music industry trade show in New York. She wrangled a bunch of media attention for the show, including a major spot on VH1. Her early success and the fun of the event itself—Lisa Loeb held a songwriting seminar—made Sol feel like she had arrived. A few years later, she co-founded Vine Communications, her own firm in Miami.

“I found that the freedom of getting clients in front of who they wanted to be in front of was liberating. It’s so much better than, ‘Does this have a bleed?’” she said, referring to the text on a page that spills over the print area. “It’s like, who cares?”

Sol’s story is typical in that she fell into PR after a false start in another career—data shows that the vast majority of PR workers majored in something other than communications or marketing. Her situation is also typical, in the literal sense of the word, because Sol is a woman.

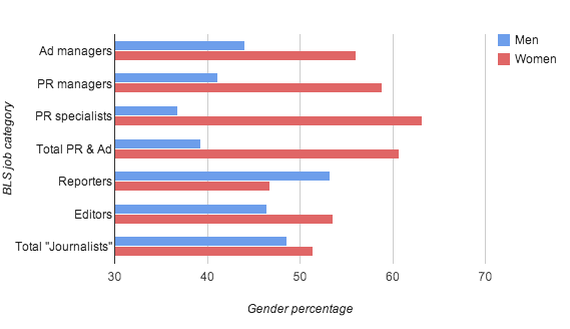

Women make up 63 percent of public relations “specialists,” according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data, and 59 percent of all PR managers. If you include the advertising world, the people shaping your media messages are 60 percent female, compared to 47 percent of the overall workforce, according to data compiled for The Atlantic by the Institute for Women’s Policy Research. Other estimates say the female percentage is closer to 73, or even 85 percent.

Those numbers are even more surprising given that the other side of the media coin, journalism, is roughly evenly split. Men are slightly more likely to be reporters, and women to be editors, but overall, the news world is 51 percent female.

At the tops of PR firms, it's a slightly different story—several women mentioned that the executives are still predominantly male. In fact, the contrast between the workers and the c-suite is so dramatic as to be maddening.

“It's all women out there,” said Sarahjane Sacchetti, who handles marketing for Secret. “And the two people running it are dudes. That's the only thing that's puzzled me and angered me for a long time.”

The growing feminization of rank-and-file publicists, though, has led a number of writers to chastise their fellow hacks for looking down on the PR Woman. The fact that there are so many women in the industry makes it seem almost sexist to cackle at a horribly conceived press release. Writing in Jacobin in June, Jennifer Pan called PR a uniquely female form of “emotional labor,” writing, “the dismissal of the publicist as a corporate shill or a purveyor of a kind of false consciousness that interferes with the otherwise unsullied work of the journalist not only reifies a gendered hierarchy of labor, but additionally eclipses the primacy of emotional labor for all workers under neoliberalism.” In other words, there but for the grace of God go you [to Ogilvy and Mather].

Ann Friedman argued in New York that we shouldn’t treat PR like “a pink ghetto.” Quoting one publicist who says she walks “the line every day between persistent and obnoxious,” Friedman writes, “Perhaps it’s time for us all to recognize that walking [that line] isn’t easy.”

I myself have wondered about this tension between reporters and publicists. I had an internship at a PR firm once, and I loved it. I liked being a 21-year-old who wrote speeches for major CEOs. (They were heavily edited, but still.) I liked the challenge of trying to make a company that makes the vacuums that suck the ooze out of diabetic wounds seem sexy. I admired how put-together my female co-workers were, with their pencil skirts and clean hair. There were always 100-calorie packs of Oreos in the kitchen.

I ultimately chose journalism, and I’ve been happy with my choice. But, especially in those first few rough years in the news biz, all uncertainty and plastic dinner plates, I wondered what might have been.

After graduation I noticed that a large percentage of my female friends were going into either public relations or a related “affective labor” field. Far fewer went into journalism. Today, the overwhelming majority of the PR pitches in my inbox are from women.

But the feminization of PR isn’t a product of some sort of mass hysteria (sorry) by female liberal arts majors. It’s very rational. Jobs for public relations specialists are growing at 12 percent a year—about the same rate at which jobs for reporter are shrinking each year. PR people now outnumber journalists three to one.

These jobs also have something that most stereotypically “female” jobs don’t have: Good pay. While female news reporters make $43,326, on average, (to men’s $51,578), female PR “specialists,” the lower-level job in the BLS categorization, make $55,705, while their male counterparts make $71,449.

“That's a pretty decent wage for a woman,” said IWPR’s president, Heidi Hartmann, “given how little they make on average.” The average for full-time female workers is $37,232.

No need to pity the PR gal, journo-ladies. She’s doing just fine.

Eighteen years ago, Deirdre Latour donned a Tony the Tiger outfit to hold a series desk-side media briefings on behalf of Kellogg’s. To be clear: That entails sitting in a newsroom. Talking face-to-face with a reporter. Dressed as a large cartoon jungle cat.

“Of course it makes me cringe now,” Latour told me.

Like in every field, there are times when communications workers question their choices. Especially at the entry level, “there are moments when you say, ‘I got a college degree, and I'm doing this?’" Latour said. “But every step of the way you learn different skills.”

Latour is now the senior director of external communications at GE—a big, high-stakes job. When GE was negotiating to buy the French energy company Alstom, Latour flew to Paris with GE’s executives to help convince the French government that GE was the right company for the deal.

But money and power aren’t everything, and there are certainly higher-paying fields that women don’t seem all that interested in entering. And the typical explanations—that women are better listeners, or more social—don't hold up, since those skills are also necessary in journalism, where women don't dominate.

So why do so many go into PR? I interviewed 10 women in public relations to find out.

Two of them I knew personally. A few more were referred to me by other journalists. The others I found by simply responding to, say, a pitch for an automated ear-cleaning device with an “I’m not interested, but would you like to talk to me for a story about yourself?”

It turns out, they did.

One reason journalists disparage PR people is that we don’t really understand what they do, having mainly interacted with them by rejecting their pitches, pumping them for information, or by grabbing a name tag from them at conferences. We don’t see the effort that goes into winning “new business,” or in mollifying a client with marathon conference calls, or in arranging the seating for an event such that dignitaries from two at-war countries don’t accidentally bump elbows over panna cotta.

“I think a lot of younger women go into PR because they think they’re going to be the glamorous Samantha Jones from Sex and the City where you’re opening up restaurants and promoting hot new clubs,” said Shannon Stubo, vice president of corporate communications at LinkedIn.

(I’ll pause here just to note that nearly every woman I spoke with mentioned Samantha Jones. It’s as though that show subtly influenced public opinion in a way we didn’t even notice.)

“Running a communications team at a global public company is extremely different and decidedly unglamorous,” she continued. “You’re playing a very critical role in the company, and you have a lot of influence and responsibility. These are people who are actually helping drive the business, not writing press releases and ‘smiling-and-dialing.”

The smile-and-dial might be the number one reason journalists grouse about PR people so much. “Do you have a minute? I’m just following up on an email I sent you a minute ago.” We only have so many minutes!

“When I first started in PR, there were a couple editors and it was part of your initiation that you had to call and pitch them because they were so mean,” Sol said. “Let's just say they were influential in the tech world. That got a little bit to their head.”

Being an egocentric journalist, my theory was always that many women found themselves in PR because it’s so hard to break into journalism. I figured that after considering becoming reporters, they thought to themselves, “Why go into a field everyone says is ‘dying’ when you can make money and have a nice life in PR?”

And indeed, some did find themselves in the field seemingly without much effort. Sacchetti, from Secret, admits that she picked PR over a consulting job because she thought it would be easy. Latour, from GE, says she really hated her first, entry-level job at a law firm, so she visited a headhunter, who suggested PR.

“I said, ‘what’s PR?’” she recalled.

Others thought about journalism but were daunted by how unstable and low-paying it seemed.

“My mom always wanted me to go into journalism,” said Ellie Rutledge, who worked in PR at a big agency before recently taking a social-media role at an advocacy association. “She thought I had what it takes because I am always excited to learn and I question everything. But that’s not the aspect of journalism I see anymore. There’s not a lot of room to pick your stories based on what’s important to learn about; it’s about what gets the most readership, and most often that isn’t newsy.”

Cait Douglas, director of communications for the U.S. Travel Association, worked for the college paper at American University before concluding that the early stages of journalism were far more grueling than those of PR.

“You might have to go to a small town to create your career,” she said. “With PR, there's a lot of opportunities no matter where you are.”

At the same time, many of the women had their own misconceptions about journalism. A big one was that reporters are all deadline-obsessed copy slaves.

“I always felt like journalism was so competitive, and I didn’t like the idea of being forced to write on a timeline,” Rutledge said. “Writing is the part of my job I always procrastinate on!”

(I'm still waiting for the day that journalists stop procrastinating and my Twitter feed falls silent.)

“If you're a news-focused journalist, it's a much harder job,” Sacchetti said. “You have to be on all the time and you never get a weekend.”

Journalists do work long days, but it’s not exactly investment-banker hours. And given the nature of our work, if that were true you’d see a lot more think pieces about the miserable reporterly life.

And PR can be intense in its own right: Stubo said her day starts at 5:15 a.m. and ends late in the evening. “There is a break in professional work when I am with my children (ages 2 and 4) between 5:00 p.m. and 8:00 p.m.,” she said, “And then I’m back on the phone or email until 10:00 p.m. I have between 12 and 14 meetings each day, and I am a member of our company’s Executive Team. I am up to speed on nearly every important issue at the company and am called upon multiple times per day for guidance.”

Others never considered journalism, having set their sights on PR early. Chantelle Karl, a PR consultant who formerly worked for Yelp and others, worked her way up from an internship with Marianna Marino, an independent PR practitioner in the Bay Area, during her junior year of college. Because the internship was unpaid, she worked long days with Marino and spent nights folding clothes at Banana Republic. This sounds not dissimilar to my first unpaid internship in journalism, which I completed while working 25 hours a week at a stationary store and living in a one-bedroom apartment with three other people.

It seems like, at least in more recent years, college students are preparing for communications careers purposefully. In an analysis of the American Community Survey, Philip N. Cohen, a professor of sociology at the University of Maryland College Park, found that 47 percent of women and 35 percent of men who are public relations specialists or managers majored in communications, journalism, English, advertising/PR, business, and mass media—all majors that would lead naturally to a PR career. Communications was the most popular major for both genders, at roughly 10 percent for men and 15 for women, and journalism was a distant second (or third, in the case of men.)

“It looks like women are more likely than men to prepare for [a PR] career in college,” Cohen said.

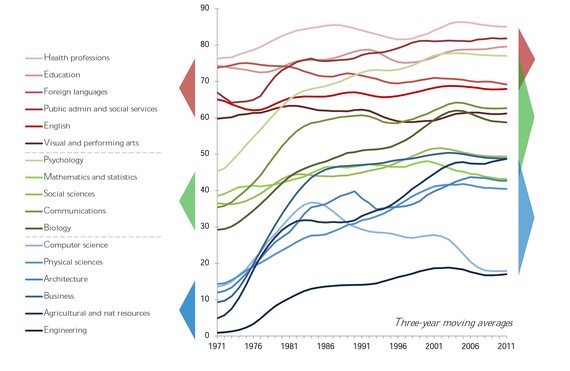

Meanwhile, women decidedly do not major in fields that could lead to other types of high-paying jobs, like in engineering or computer science. Another analysis by Cohen found that while women are majoring in formerly male-dominated fields like psychology and biology in greater numbers, the share of female computer-science majors has actually declined since the mid-1980s. The share of men in traditionally female fields like education, English, and social work, however, has barely budged.

One study found that the difference in majors can be chalked up to the fact that women tend to value “non pecuniary,” or non-monetary aspects of their college majors slightly more than men do, while men value their potential future earnings slightly more.

“No one ever encouraged me to do math or science, so I did liberal arts,” Latour said. “I didn't know what to do with a history major. I tried this, and it happened to be really right for me. I think it's a reflection of how women in society are educated. The idea that women are better at communicating or listening; I think that's old-fashioned.”

This is where the women-in-PR conversation gets uncomfortable and squirmy. The idea that women are somehow “naturally” more social, collaborative, or chipper, and that this leads them organically into a PR career, is a message that could use the palliative touch of a Don Draper or Peggy Olson. Or as a PR person might say, I have some exciting findings to share with you, direct from a sociological minefield.

There is some evidence that women tend to be more collaborative, participative, and pro-social than men are—but that’s impossible to untangle from our societal expectation that they be that way. Women have only been found to talk more than men when they’re in collaborative settings. Women are expected to be happier and to smile more than men. Subjects in clinical studies will more readily identify androgynous, angry-looking faces as male, but they will view androgynous happy faces as female. People will consider female leaders effective when they demonstrate both sensitivity and strength, but the male leaders need only to demonstrate strength. The only way to get study subjects to rate two fictional, identical executives named “Susan” and “James” similarly is if “Susan” hints that she makes efforts to “promote a positive community.”

Women may be drawn to PR because they feel they’re collaborative and social, but we’ve also socialized most of our women to be that way.

Regardless, this was repeatedly cited as one of PR’s biggest draws:

“Studies have shown that women tend to collaborate more and prefer to work on teams, whereas men usually do better in competitive environments and prefer to fly solo. That male approach works well for journalists, while having a bit of a 'people-pleaser' gene probably attracts and/or makes it easier for women to excel in the PR environment,” said Jennifer Hellickson, director of marketing at SweatGuru in Portland, Oregon.

Sol surmised that it’s because women are better at multitasking, which she says is also essential for PR.

“Having your hands in a lot of different pots is a big part of being in an agency,” she said. “That appeals to a woman's ability more so than men. Men tend to be more singularly focused.”

While studies have shown that the two halves of women’s brains are more interconnected, the idea that women are better at multitasking hasn’t been supported by research. In fact, many scientists doubt the idea that humans—male or female—are even capable of attending to two or more things at once.

Several of the women also seemed to enjoy working “behind the scenes,” while the average reporter enjoys clawing for bylines. Sol said being on camera was her “worst nightmare.” Stubo said her dream job was being Katie Couric’s publicist.

“It's interesting to see people who were journalists who made the flip to PR, and what a challenge that is to do that,” Sol said. It can come as a shock to be on the other side of the “publish” button.

The other big gender difference, for those deciding between PR and journalism, was that PR struck them as inherently less risky. Several studies have found that women in the job market tend to be more risk-averse than men because they are faced with steeper costs when they switch jobs: They have lower odds of being re-employed and they tend to spend more time in unemployment.

Men are also more risk-prone in other contexts (they’re more likely to cross busy roads, for example), but this, too, is largely a matter of socialization.

“Men love the chase; an explosion or car chase makes a very appealing story for a man,” said Jessica Chesney, a digital marketing coordinator at Command Partners in Charlotte, North Carolina. “So it could be the action and excitement that influences their decision to enter journalism.”

Hellickson earned a bachelor’s degree in magazine journalism, and she had initially planned to move to New York after college to try to get her foot in the door of a major glossy.

“But that thought quickly faded when I learned more from classmates and colleagues about the high competition and low compensation,” Hellickson said. PR, she said, offered everything she loved—writing, storytelling, networking—all with the stability of the billable hour.

Despite their knack for spin, the women I spoke with weren’t blind to PR’s downsides. Several cited the fact that their schedules were unpredictable and clients seemed impossible to please.

“It's a bit of a thankless endeavor—when PR is good, everyone is off and planning for the next thing; but when PR is bad, it's all anyone can talk about,” Hellickson said.

Pitching journalists can fray even the most “communal” and “social” of nerves: “The reporter wouldn't want it, but you had to at least try,” Sacchetti said of past jobs. “You almost sometimes knew you were doing it to get the no. It was difficult. It wasn't fun.”

Others thought there might be sinister implications to the gender imbalance. “Are some of the few men in PR only seeking those positions to be around women all the time?” Chesney said. “It's so sad to say, but I heard a guy in PR say that's why he got into PR in college.”

Still, those who were dedicated to the field thought it allowed them to rise to the top in a way that other professions don’t. Sarah Rothe, a media manager at Golin in Chicago, said the industry’s female role models inspire her, noting that Golin had recently added two women to senior roles: a “Chief Creative and Community Officer” and a “Chief People Officer.”

“I think PR offers women the opportunity to hold high-level, corporate positions, so the career-oriented find empowerment in a PR position,” Chesney said. “We see it on Sex and the City, we see it on Mad Men and we see in a ton of other places; these women portray power and they have it all.”

If there’s any takeaway from all this, it’s that the women-in-PR trend started happening for a number of reasons, and it’s not inherently bad, so it never stopped. I get the idea that the average girl is brought up believing that it’s good to be personable and collaborative. She gets to college, and classes that involve reading and writing appeal to her the most. She graduates and, like any rational actor, gravitates toward the field that will remunerate her best—and maybe even provide some stability so she can have a family.

Then another force takes over—something that happens to people in all walks of life—which is that after you do something for long enough, you start to thrive in it, and then you start to think of yourself as “a ____ person.” And then you never leave.

Many of the women I spoke to seemed to genuinely enjoy portraying things in a positive light, which is the exact opposite of most journalists I know, who appraise every fact they encounter with the skepticism of an overzealous hall monitor. "Oh a special ranch for disabled ponies? How disabled are the ponies, though?"

After a while, PR women are what they are because they’re just really good at selling.

“I really enjoy connecting the dots, figuring out what the journalists are working on,” said Megan Laney, a senior account executive for Launchsquad in Portland, Oregon. “I work with clients on developing their stories. We work with cool clients who are really interesting to me.”

“For example,” she couldn’t resist adding, “we work with a bra and lingerie brand—they're using data to create better bras for women. They're really cool. You should check them out.”