Carlos Slim, the Mexican telecoms billionaire and philanthropist, this month regained his position as the world's richest man (£42bn), temporarily lost to Bill Gates last year. So, when he speaks, his gold-plated peers listen. Last week, he announced at a business conference in Paraguay his latest big idea – a global three-day, 33-hour week on full pay for workers moving into their sixth and seventh decades, and not yet ready to retire.

According to one estimate, deferring the pension age by 12 months in the UK could save £13bn a year. It seems a very long journey from the ordinances of the London Weavers' Guild in 1321 to reduce the long working day, the 14-hour shifts that marked the Industrial Revolution and Henry Ford's 1914 revolutionary notion of the large-scale assembly line, but the theme is the same. Namely, the value of "free" time to the working man and woman balanced against the profit and loss of employment.

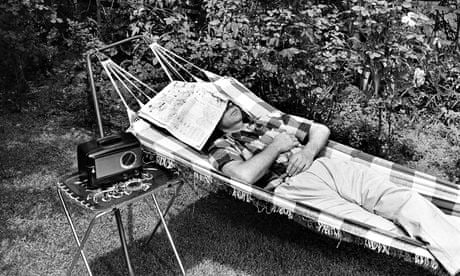

This is the beginning of the summer holidays for many. It means for some a fortnight of liberation from paid work, "doing nothing" bar domestic duties, entertaining children and demonstrating tact with the visiting inlaws and trying to coax various pieces of equipment in the rented cottage/caravan/camp site into functioning without serious personal injury. This, the luxury of work-free time, however brief, means greater autonomy, less stress, relationships revived and opportunities to develop interests that may be of little value in monetary terms, but which enrich the soul. At least, that's the theory.

"Time off" helps to focus the mind on the advantages of the shorter working week while it immediately raises a number of problems – both psychological for the workaholic and those in love with their jobs (a minority, apparently, since the global Blessing White survey reports that only 31% of the workforce in Europe say they are "engaged' in what they do), and practical, not least for those on low pay, contemplating an income still further reduced.

However, given the scale of the challenges the world faces, for example in the devastation of its natural resources and the impact of ageing populations, reducing the paid working week has a number of advantages as the thinktank, New Economics Foundation (Nef) and the TUC, among others, have argued for years.

In 21 Hours, for instance, a Nef paper published in 2010, Anna Coote argued that such a reduction would create more jobs. (The French government claimed that its 35-hour week – "Work less. Live more" – created 350,000 jobs before it was axed in 2008 under the slogan: "Work more to earn more.") A 21-hour week would also restrain consumption since lower wages would mean less cash to flash, reduce high carbon emissions, tackle inequalities and improve well-being.

A short week may seem unlikely but working patterns have proved remarkably flexible, particularly when driven by the desire to maximise profits. Since 2008, for example, the proportion of people working on temporary and zero-hours contracts has increased greatly. Even earlier, the arrival of women in the workplace in significant numbers in the 1970s introduced still greater variety or what a report by the Recruitment and Employment Confederation last week called "flex appeal". Job share, annualised hours, term-time working and compressed hours all framed in the language of "family friendly" and "work-life balance" have, in practice, too often meant low wages and the forfeit of advancement.

Now, there is a slowly growing corporate understanding that employees respond better to greater control over when they clock in and out and what matters is the outcome, not the hours a task takes.

That, plus a combination of technology and the growth of the knowledge economy, is initiating even greater change. Microsoft, for instance, under the slogan "Any time any where", allows working from home while Unilever advocates "agile working". Companies such as National Grid and BT say diversity in work patterns results in greater retention of staff and lower recruitment costs, among other advantages. Unions and the employers in the highly successful UK car industry reduced hours to retain more jobs during the worst of the recession.

In 1930, John Maynard Keynes predicted that employees would toil for only 15 hours and then face the challenge of "how to use freedom from pressing economic cares". The long-predicted "leisured society" has yet to arrive for the UK workforce, but further reshaping of the working week is highly likely and to be welcomed, not least because while unemployment can be deadly, work may also make us sick. According to the Health and Safety Executive, in 2011-12, 22.7 million working days were lost due to work-related illnesses.

Last week, a study published in the British Medical Journal said that shift work, previously linked to an increased risk of high blood pressure and diabetes, may also raise the risk of a heart attack by almost 25%. Again, earlier this month, John Ashton, president of the UK Faculty of Public Health, called for a four-day week to combat a rising tide of stress and the lack of time to recuperate properly.

Professor Lynda Gratton of the London Business School has spent five years considering the future of work in conjunction with 21 global companies, including Nokia, BT, Save the Children and Singapore's ministry of manpower. One manifestation of the difficulties that young people today face in securing work, and expecting not a job for life but many changes and switches in career, she says, is that increasingly, they value the quality of their lives and time for themselves as much if not more than status and high pay, a rejection of what the late historian EP Thompson called the notion of time as "a currency – not passed but spent".

The global work place is a contradictory universe; progress is uneven. In some parts, the horrific conditions of the British Industrial Revolution continue while in the Swedish city of Gothenberg a one-year experiment is underway in which some of its employees enjoy a six-hour day to see how their performance compares with those on the standard eight hours, on the basis that fewer hours may prove more productive and enhance creativity.

"Time's arrow is broken," wrote Richard Sennett in The Corrosion of Character. "It has no trajectory in a continually re-engineered, short-term…. political economy." Out of austerity and necessity, however, it's just possible that such pessimism may be challenged. We may yet be forced to reshape work and, in the process, revalue what is among the most precious of all commodities – our free time.