Hollingbury Copse is a pleasant suburban cul-de-sac on the northern outskirts of Brighton, but nothing remains of the curious property that once stood here, and was the first to have this address. It was built amid dense woodland in the late 1870s by the celebrated Shakespearean scholar and collector James Orchard Halliwell-Phillipps. The views across the downs and out over the Channel were splendid, but the house itself was not the commodious sort of residence one might envisage for this eminent if eccentric Victorian. It was not really a house at all, but a rambling spread of single-storey timber buildings, roofed with galvanised iron and connected by wooden corridors. An early visitor likened it to a squatters' camp in South Africa, but with time it mellowed. An American journalist, Rose Ewell Reynolds, who saw it in 1887, thought it very "picturesque" – it was "simply a collection of bungalows bought ready-made in London, but grouped as they were they made a most comfortable home". They had "criss-cross timbering on the outside", which reminded her of the "quaint little houses" she had seen in Stratford-upon-Avon.

Halliwell-Phillipps called it his "rustic wigwam" or – with a characteristically dreadful pun – his "Hutt-entot village". He lived here for the last 12 years of his life, breezily describing himself as a "retired old lunatic" and a "queer recluse" with "a fancy for doing as he likes without caring a button for public opinion", though these bluff disclaimers belie the intense productiveness of this late period at Hollingbury Copse.

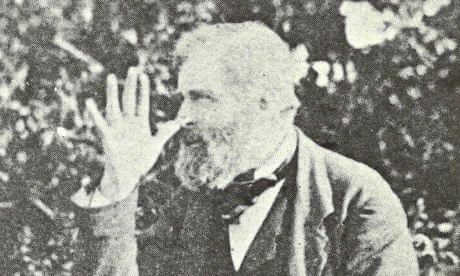

When he moved here in 1877, in his late 50s, he was at a low ebb. He was suffering from migraines and depression, was drinking heavily, and was dependent on opiate sleeping-draughts. His wife Henrietta, an invalid for many years after a riding accident, was in terminal decline and would die in a nursing home in 1879. He was exhausted by the squabbles and snobberies of the Victorian scholarly world, and felt his prodigious energies as a writer and researcher seeping away. Hollingbury was his escape from it all, indeed he came here under doctor's orders. A photograph (above) shows him at this time: a big, grey-bearded man in a crumpled suit and old-fashioned ribbon-tie. He is posed in profile, and he is thumbing his nose. A handwritten caption below reads: "My reply to the idiots who ask me to resume literary studies." But it seems the medicine worked, and under this regime of sylvan seclusion and bracing sea-air – not to mention a young and by all accounts devoted second wife – he was soon back in business, in the study which he referred to simply as his "workshop".

In his log-cabin retreat Halliwell-Phillipps kept, and obsessively curated, his huge collection of "Shakespearean rarities". This consisted of "about fifteen hundred separate articles" – a cornucopia of manuscript papers and parchments, early quarto editions, play-bills, portraits, maps and curios carved from the sacred mulberry tree. It furnished, he believed, "more record and artistic evidences connected with the personal history of the Great Dramatist than are to be found in any other of the world's libraries". The cataloguing of this collection was one of the unfinished labours of these years. The first thin handbook, A Rough List of the Shakespearean Rarities at Hollingbury Copse, appeared in 1881. It was followed by the Brief List of a Selected Portion of the Shakespeare Rarities that are preserved in the Rustic Wigwam at Hollingbury Copse (1886), in which he describes 47 items kept in his study, and one prize possession – the unretouched "first state" of the Droeshout engraving of Shakespeare – on display in the dining room. The last and fullest catalogue, the Calendar of the Shakespearean Rarities (1887), itemises some 800 pieces, little more than half the collection. In the preface to the Calendar he confronts the probability of non-completion with jocular bravado: "As our Brighton whip in the old days of coaching used to say, 'Tempus will fudgit', and it has fudgited with me until there is but a little working slice of it left." These catalogues were privately printed at Brighton, in very limited runs, and have become slight rarities in themselves.

Halliwell-Phillipps had been collecting books and manucripts since his teens – his first interests were scientific and medieval: the Shakespeare obsession came later. He also frequently sold objects when money was tight: "bookcase full after bookcase full", he wrote ruefully, "were disposed of under the vibrations of the auctioneer's hammer". The Sotheby's catalogues are full of him. A sale in the summer of 1857 earned him over £1,000. Among its treasures were the original mortgage-deed on Shakespeare's house in Blackfriars, signed by the poet on a pendant strip of parchment (sold to the British Museum for £315), and Shakespearean first editions such as the 1609 Sonnets (£154) and the 1600 quarto of Henry IV, part 2 (£100); as well as much trivial memorabilia such as "the heel of the shoe kicked off by Mrs Siddons in throwing back her velvet train whilst performing the part of Constance in King John".

A slightly dodgy air of opportunism and profiteering hangs over his dealings. His reputation was nearly ruined in 1845 when he was accused of having stolen and subsequently sold some rare scientific codices from the library of Trinity, Cambridge, his old university. They had gone missing some eight years previously, when he was an undergraduate there. The case against him was circumstantial and did not get to court, but for a while the newspapers covered it, and even the prime minister, Sir Robert Peel (a trustee of the British Museum, which had bought the codices) found himself embroiled. According to the bibliographical investigator Arthur Freeman (whose book about the forgeries of John Payne Collier runs to over 1,000 pages) Halliwell-Phillipps's guilt "now seems more likely than not … [His] book-trading behaviour was not always as scrupulous as his scholarship". Other darker allegations of theft – including a 1603 quarto edition of Hamlet, one of only two copies then known to exist – remain unproven.

He is also notorious for his pragmatic habits as a bibliophile. By today's standards of book conservation he belongs to the era of the big-game hunter. In pursuit of a "perfect copy" of an old book – there are many thus described in the Hollingbury collection – his favourite tools were a stout pair of scissors and a paste-pot, used to supply missing or defective pages in one copy by mutilating another. Other pages, sometimes whole chapters, would be "exported" to his gigantic collection of scrapbooks. In extenuation one might say there were a lot more old books around then, and imperfect copies were considered fair game. Also, the available technologies for copying texts – autotypes, collotypes, photogelatins etc – were expensive. The labour of manual transcription was the bottom-line of his titanic researches, and resorting to the cut-and-paste option is understandable.

Halliwell-Phillipps is hardly a fashionable name today; you are unlikely to hear him much mentioned in the celebrations of Shakespeare's 450th birthday this month. He has a fusty, dusty, Dickensian air that does not fit well with conferences and critical theories. He is too verbose and voluminous, too portentous and pernickety. But I think it is worth remembering him, and indeed championing him, as one who brought us closer to Shakespeare through actual documentary "evidences" – his favourite word.

Halliwell-Phillipps as collector is part of this, and his bunker full of Shakespeareana on the Sussex Downs is a physical result of it, but his most enduring legacy was as a biographer, and his crowning achievement, Outlines of the Life of Shakespeare, was another product of the Hollingbury years. It was both a summing-up of decades of research, and a kind of open-ended, ruminative gloss on the nature and sources of the data he is using. One might call it his swansong, or perhaps rather his long goodbye. The first edition, published in 1881, ran to less than 200 pages: it was, he said, a "mere unfinished instalment". Further editions followed, each revised and enlarged from the previous one, and by the seventh and final edition of 1887 it had swelled to two tall volumes totalling 848 pages, nearly two thirds of them close-printed appendices, transcripts and "illustrative notes".

"I have no favourite theories to advocate, no wild conjectures to drag into a temporary existence, and no bias save … submission to the authority of practical evidences," he wrote in the preface to the Outlines. He rejected the "temptation" of trying to "decipher" Shakespeare's "inner life and character through the media of his works" – a temptation to which his contemporaries routinely yielded. For the epigraph he chose the famous words of Ben Jonson about honouring Shakespeare's memory "on this side idolatry". These seem admirable precepts, even if his work does not always succeed in avoiding the pitfalls of conjecture and indeed idolatry.

The collector and the biographer are twin guises of a single obsession, and both depended on his extraordinary skills as an archival detective, and on the long rugged labours he devoted to the art he called "rummaging". Probably his most important work was with the local records in Stratford-upon-Avon. From his study at Hollingbury Copse he recalled his first encounter with them some 40 years previously – thousands of documents crammed into boxes, "the ancient ones tangled with the modern in wild confusion. Some were crumpled and slightly mutilated, but nothing like decay had set in … There was, it is true, no end of dust, but that is an object in a record-room as welcome to the eyes of a paleographer as the presence of drainpipes in a clay field is to the farmer." He meant that dust indicates the absence of moisture, the "most dangerous of enemies" to an archive, but there was another reason also for rejoicing. Dust was a sign that the records were undisturbed by previous researchers – no footsteps in the snow.

What he laboriously uncovered and transcribed was a wealth of fragmentary detail touching on Shakespeare's "other" life as a provincial landowner and family-man – the property deals and minor lawsuits, the pressurising of debtors, the hoarding of malt, the quarts of claret and sack disbursed to a visiting preacher – and out into the penumbra of family associations stretching from his yeoman grandfather Richard Shakespeare to his childless granddaughter and last lineal descendant, Elizabeth Barnard. Much of what he found could be called prosaic, but this was precisely the stuff he relished. His aim was to grasp a sense of the daily, mundane texture of Shakespeare's life. This ran counter to the general adulation – almost deification – of Shakespeare that had taken hold in the later 18th century, particularly after the bicentennial of 1764 orchestrated by the actor David Garrick. According to James Shapiro's book Contested Will, it was the apparent disparity between these two identities – "between Shakespeare the poet and Shakespeare the businessman; between the London playwright and the Stratford haggler" – that blew up that great bubble of fruitless conjecture known as the "authorship controversy", launched on an unsuspecting world by Delia Bacon in 1856.

Halliwell-Phillipps did further valuable work on the physical and local fabric of Shakespearean Stratford, rescuing from dilapidation the family home on Henley Street where Shakespeare was born and grew up; and leading the first archeological excavations on the site of New Place, the house that had been purchased by the successful playwright in 1597 and demolished in the 18th century by its choleric owner, the Rev Francis Gastrell, so he could be free of importunate tourists. For the frontispece of his Outlines, with so much pictorial and manuscript material to choose from, Halliwell-Phillipps opted for an almost minimal engraving that shows the foundations of an original outbuilding at New Place, uncovered in one of his digs. It imbues his great summa biographica with an unexpected sense of the vestigial: how little of substance remains for the historian to work from.

The last photograph, very faded and ghostly, shows him standing in the Hollingbury woods, white-bearded but still vigorous-looking. Ever the joker, he is dressed like a pantomime tramp, complete with staff and knotted kerchief over his shoulder. He died in the first days of January 1889, at the age of 68. His widow remarried quickly and moved to Dorset. The wigwam was put up for sale at what the prospectus called the "upset price of 6,000 guineas", but it found no buyers, and sometime around the end of the century it was demolished. The collection of rarities – or at least a good portion of it – was purchased in 1897 by Marsden J Perry of Providence, Rhode Island, and is now safely, if less picturesquely, housed in the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington DC. The old scholar-tramp himself lies in a corner of the parish churchyard of All Saints, Patcham. The grave is neglected and overgrown, its modest inscription smothered in ivy like a lost text awaiting discovery.

This is an edited version of Charles Nicholl's inaugural lecture as honorary professor in the School of English at Sussex University.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion