The Vault is Slate’s history blog. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter @slatevault, and find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

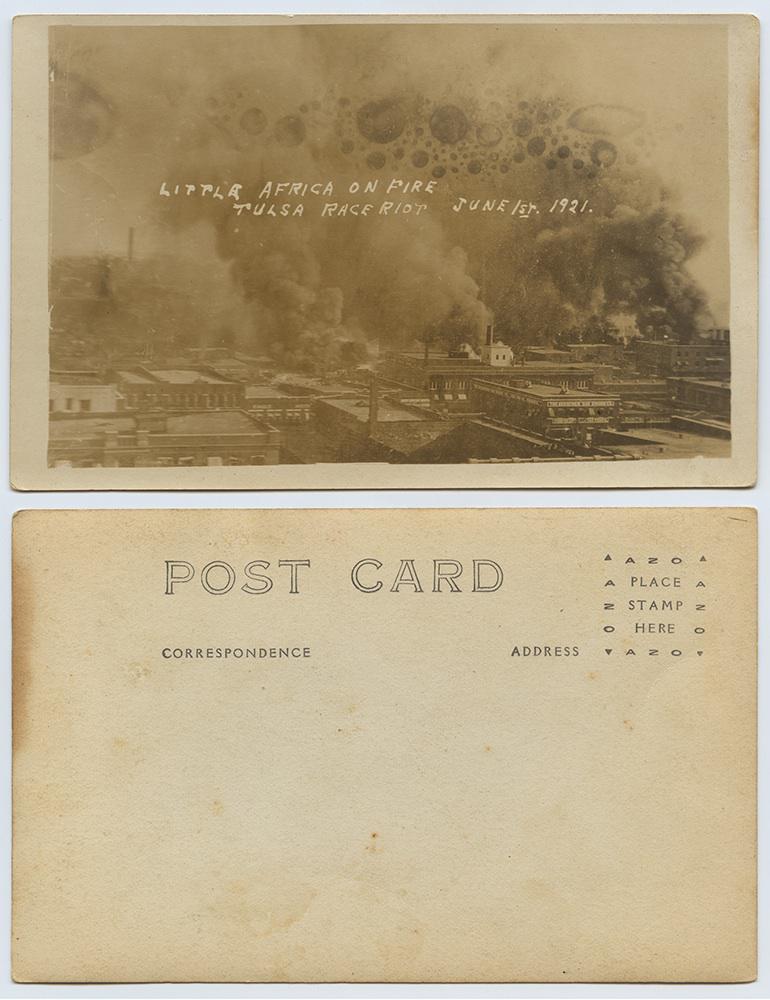

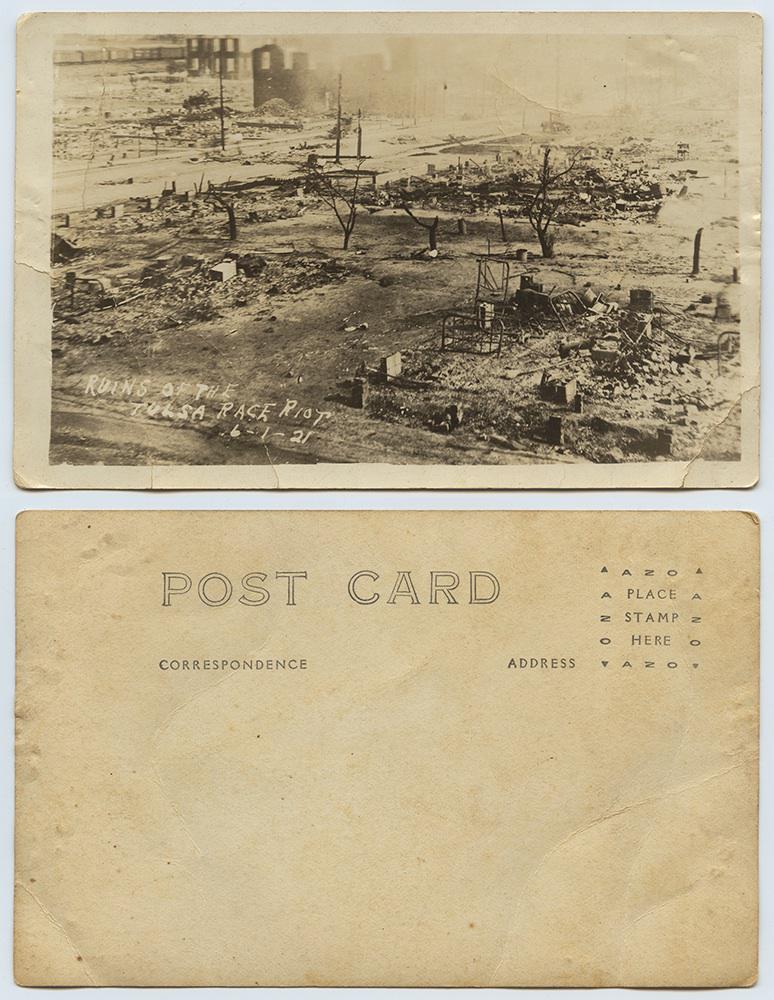

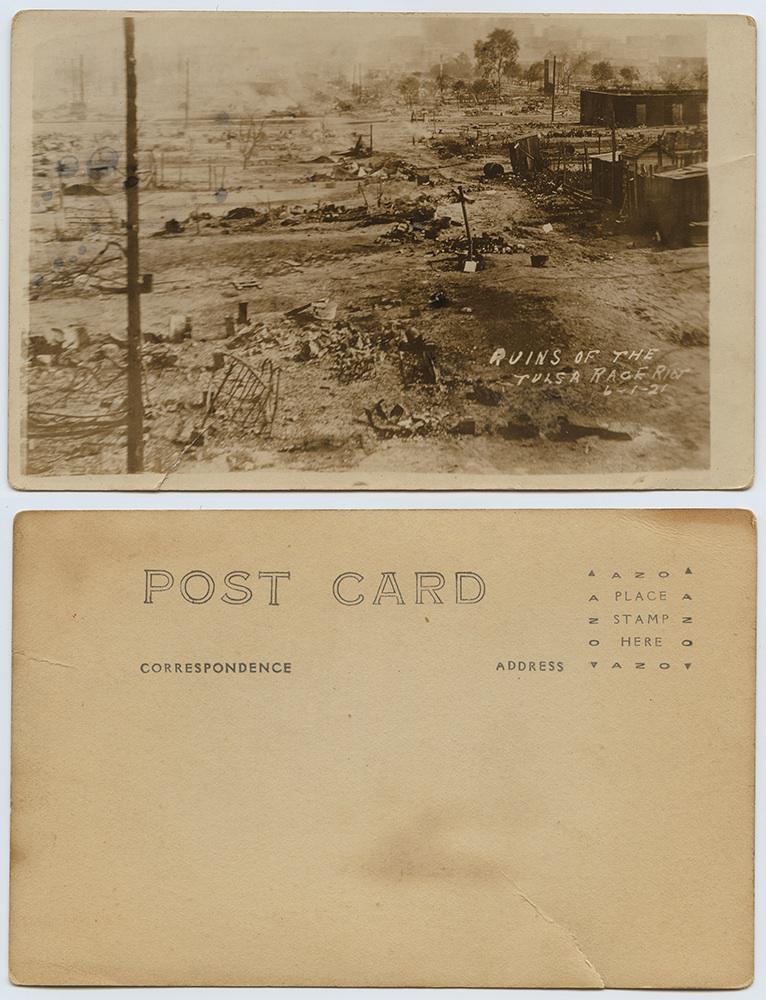

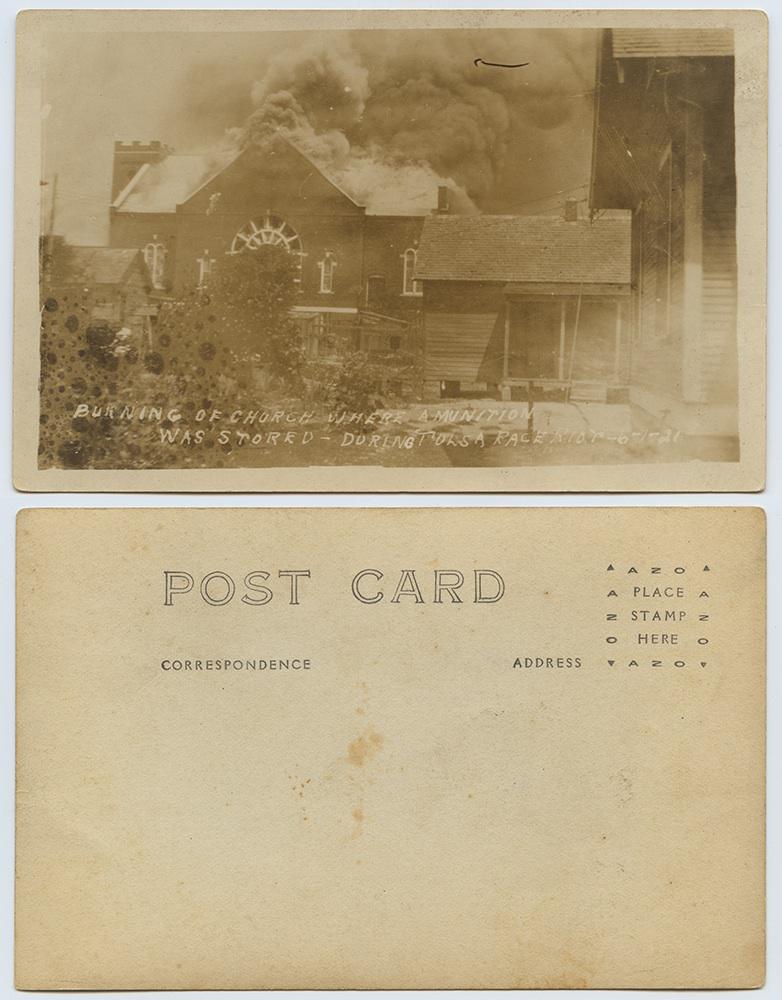

These images, made into postcards, commemorate the destruction brought on by the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot, capturing the ruins that replaced the city’s black neighborhoods after 18 hours of looting and burning. These postcards, like the images of lynching victims that circulated in the mail around the same time, served as souvenir objects for white collectors, celebrating the destruction that had taken place.

Although the origins of this violence are somewhat obscure, it seems that a chance encounter between Sarah Page, a young, white, female elevator operator, and Dick Rowland, a young black man riding her elevator, touched off the riot. On May 30, 1921, Rowland accidentally stepped on Page’s foot. Page screamed. In many places in the United States in the 1910s and 1920s, raciall -motivated vigilante violence was common. White Tulsans amplified the elevator incident, eventually accusing Rowland of rape.

After attempting (and failing) to lynch Rowland, a mob of white vigilantes attacked black neighborhoods with guns and torches. The Greenwood district, which was rich in black-owned businesses, made an attractive target for white Tulsans bent on revenge. While the black residents tried to hold off the mob, numbers eventually prevailed, and much of Greenwood was burned.

Casualties numbered between 50 and 300, though precise numbers are hard to pin down. (I. Marc Carlson, a librarian and researcher at the University of Tulsa who maintains a website about the race riot, has compiled a list of the casualties, along with their injuries, as recorded in contemporary sources.) In a lasting blow to the community, around 1,200 homes were rendered uninhabitable.

In his book about the riots, law professor Alfred Brophy points out that black and white Tulsans each used photographs for their own purposes after the violence ended. White Tulsans celebrated the obliteration of the Greenwood district, buying and selling postcards like the ones below (as well as postcards featuring much more disturbing images).

Meanwhile, the newspaper Black Dispatch “offered its readers a three-foot-long picture” of the wreckage as a subscription incentive later in 1921. “Showing the ‘desolate, smoking ruins of the Tulsa Riot,’ ” Brophy writes, “the paper celebrated ‘the heroism of the valiant black men and women who have remained in Tulsa and made of that charnel house a fit place for our group to live.’ ”

Southern Methodist University, Central University Libraries, DeGolyer Library.

Southern Methodist University, Central University Libraries, DeGolyer Library.

Southern Methodist University, Central University Libraries, DeGolyer Library.

Southern Methodist University, Central University Libraries, DeGolyer Library.