Anyone with an interest in Roman Britain should have St Albans on top of their list of places to visit. I myself visited St Albans twice and enjoyed it on both occasions. A short train ride north of London, St Albans is a must-see site. There are a few remains of the Roman town still visible (Verulamium), such as parts of the city walls, a hypocaust in situ under a mosaic floor, but the most spectacular are the remains of the Roman theatre.

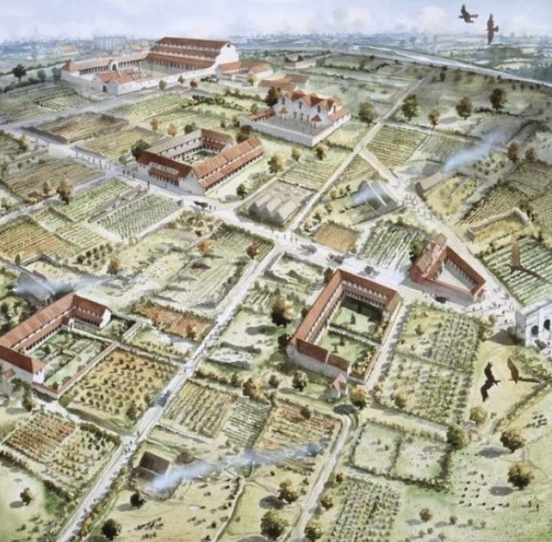

In its heyday Verulamium was the third largest city in Roman Britain. The city was founded on the ancient Celtic site of Verlamion (meaning ‘settlement above the marsh’), a late Iron Age settlement and major center of the Catuvellauni tribe. After the Roman invasion of 43 AD, the city was renamed Verulamium and became one of the largest and most prosperous towns in the province of Britannia. In around AD 50, Verulamium was granted the rank of municipium, meaning its citizens had “Latin Rights”. It grew to a significant town, and as such was a prime target during the revolt of Boudicca in 61 AD. Verulamium was sacked and burnt to the ground on her orders but the Romans crushed the revolt and Verulamium recovered quickly.

By 140 AD the town had doubled in size, covering 100 acres, and featured a Forum with a basilica, public baths, temples, many prosperous private townhouses and a theatre. Despite two fires, one in 155 AD and the other around 250 AD, Verulamium continued to grow and remained a central Roman town for the next four hundred years until the end of the Roman occupation.

Today the site of Verulamium sits in a beautiful public park. Archaeological excavations were undertaken in the park during the 1930s during which the 1800-year-old hypocaust and its covering mosaic floor were discovered. Further large-scale excavations uncovered the theatre, a corner of the basilica nearby and some of the best preserved wall paintings from Roman Britain. On the outskirts of the park is the Verulamium Museum which contains hundreds of archaeological objects relating to everyday Roman life. Today these artefacts from Verulamium form one of the finest collections from Roman Britain.

The Roman Theatre

The Roman Theatre of Verulamium, built in about 140 AD, is unique. Although several towns in Britain are known to have had theatres, this is the only one visible today. It was discovered in 1869 on the site of the original Watling Street that run from Londinium (London) to Deva Victrix (Chester) and was fully excavated in the 1930s.

The theatre was built close to the site of an earlier water shrine and was linked to two temples dedicated to Romano-British gods: one stood immediately behind the theatre and the other on the opposite side of the river a short distance outside the town. Today the remains of these temples lie buried.

The theatre could accommodate several thousands spectators on simple wooden benches and had an almost circular orchestra in front of the stage where town magistrates and local dignitaries were seated (see illustration) . By 160 AD-180, the theatre was radically altered with the stage enlarged.

Religious processions and entertainments like wrestling, bullfights, sword fights and gladiatorial contests occasionally took place in the theatre. Plays by Latin and Greek authors were also performed at religious festivals as well as pantomīmae (pantomime shows). Its fine acoustics were perfectly suited to musical and dramatic performances.

The theatre was lined with shops with storage spaces behind the main shop area and even sleeping quarters. A covered walkway along the street provided shelter for customers and goods for sales. When the shops were excavated in the 1950’s, broken crucibles and waste metal showed that most of the shops had been occupied by blacksmiths and bronze workers.

Around 170 AD a large townhouse was built behind the shops part of which can still be seen. The house had a hypocaust and an underground shrine.

The Hypocaust and Mosaic

During the 1930s excavations, archaeologists uncovered a 1800 year old underfloor heating system, or hypocaust, which ran under an intricate mosaic floor. By 150 AD it was the custom for aristocrat’s houses to have at least one or two rooms heated by hypocausts and fine mosaic floors. This floor is thought to have been part of the reception rooms of a large town house built around 180 AD. Part of the west wing of the house is preserved in situ and is on public view in the Verulamium Park.

The mosaic is of great size and contains around 200,000 tesserae. The floor is composed of a central section with 16 square panels, each containing a circular roundel with a geometric design. The borders are bands of single and double interlaces and strips of wide and thin dark and light material.

The hypocaust was stocked from a small room outside the main house, and the stockehole of its furnace is visible below a glass floor panel. Heat passed through flues beneath the mosaic, one has collapse and can be seen.

The City Walls and Gateway

A rather long section of the city walls of Verulamium can still be seen today. The walls were constructed around 270 AD and were over 3m thick at foundation level and over 2m high. They were built as a complete circuit round Verulamium with a total length of 3.4 km (2.25 miles) and enclosing an area of 82 ha (203 acres). This made Verulamium the third largest walled city in Roman Britain behind Corinium (Cirencester) and Londinium (London).

Large gateways controlled the four main entrances to the town of Verulamium. The best preserved is the London Gate on the south side of the town. All four main gates were massive structures with double carriageways and narrow passageways for pedestrians.

The Verulamium Museum

Located in Verulamium park, the Verulamium Museum was established following the 1930s excavations carried out by Mortimer Wheeler and his wife Tessa Wheeler.

Wandering around the rooms, one can learn how the ancient town was built, how the inhabitants of the city made a living and also how their dead were buried.

This award-winning museum houses an outstanding collection of Roman mosaic floors, some of the best Roman wall paintings to have survived in Britain and a vast collection of small finds, from the most humble to the magnificent. A range of rooms from various houses have also been recreated giving the visitor an opportunity to discover the life and times of a major Roman city.

The Mosaics

The remains of more the forty mosaics have been found at Verulamium, some of them being the finest ever found in Britain.

The Wall Paintings

Surviving painting frescoes are rare in Britain and the Verulamium Museum is exceptional in having several well-preserved wall paintings. Most designs imitate marble veneers, columns and cornices, giving an impression of wealth and luxury.

The Basilica Inscription

Despite the long settlement history of Verulamium, there remains little evidence of the Roman occupancy period in the form of stone inscriptions. However eight small fragments (RIB222 to RIB229) of a dedicatory inscription from the Basilica were found under a school playground in the 1950’s. The inscription has been reconstructed as a large dedication slab (approx. 4.3m x 1.0m).

The inscription written in a shortened form of Latin is likely to have read:

“For the Emperor Titus Caesar Vespasianus Augustus, son of the Divine Vespasian, ‘High Priest’, granted the tribunician powers nine times, hailed Imperator in the field fifteen times, consul seven times, designated consul for an eighth term, censor, ‘Father of the Fatherland’, and to Caesar Domitianus, son of the Divine Vespasian, consul six times, designated consul for a seventh term, ‘Prince of Youth’, and to all the priestly brotherhoods, Gnaeus Julius Agricola, legate of the emperor with pro-praetorian power, adorned the Verulamium basilica.”

The inscription is notable because it mentions Gnaeus Julius Agricola, the Roman governor of Britain from AD 77-84, who is otherwise known from a biography written by his son-in-law Tacitus.

Other museum’s highlights

An outstanding statuette, the so-called ‘Verulamium Venus’, is among one of the most famous finds at Verulamium. The bronze figurine probably once held central place in a household shrine. Venus stands holding a golden apple said to have been won in a beauty contest with the goddesses Juno and Minerva (though it may possibly represent the goddess of the Underworld Persephone holding a pomegranate). The statuette is one of the finest to have survived from Roman Britain.

Many beautiful pieces of Roman glass have survived intact at Verulamium because they were included in burials and thus protected from the shifts in earth movement which usually breaks fragile things like glass. In 1813 a fine glass jug was found inside a stone coffin at Kingsbury just outside the Roman walls.

A visit to St Albans will give you a good chance to see some of the most impressive Roman remains and artefacts from Britain.

Map of St Albans:

St Albans tourist information: http://www.enjoystalbans.com/