The virulent banana-killing disease that quietly stalked through East and Southeast Asia since the 1960s is now on a global conquest. Since 2013, the lethal fungus has jumped continents, ravaging crops in South Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and Australia.

It’s clear the strategies for containing the spread of Panama disease, as it’s known, aren’t working. And since the fungus can’t be killed, it’s likely only a matter of time before it lands in Latin America, where some more than three-fifths of the planet’s exported bananas are grown. In other words, the days of the iconic yellow fruit are numbered.

This latest bit of grim news about the fate of the banana comes in a new study in PLOS Pathogens. Tracing the genetic makeup of the fungus found in the various afflicted places, the research team’s analysis confirmed that the perpetrator is a single clone of Panama disease called ”Tropical Race 4,” says Gert Kema, banana expert at Wageningen University and Research Center, who co-authored the study.

“We know that the origin of [Tropical Race 4] is in Indonesia and that it spread from there, most likely first into Taiwan and then into China and the rest of Southeast Asia,” Kema tells Quartz. The deadly fungus has now leapt to Pakistan, Lebanon, Jordan, Oman, and Mozambique, and Australia’s northeast Queensland, he says.

While their findings basically prove what many banana scientists had suspected, the work highlights how little we understand about destroying the fungus—and how ineffective quarantine efforts to date have been.

Does this mean you should start bingeing on splits and smoothies right this instant? Not exactly. It takes time for Tropical Race 4 to spread. But once it takes root, the decline is inevitable. Taiwan, for instance, now exports around 2% of what it did in the late 1960s, when Tropical Race 4 was first discovered there.

If this story sounds familiar, it might be because it’s happened before. As Quartz detailed in 2014, in the late 1800s, Race 1—the current strain’s elder cousin—laid epic waste to Latin America’s banana plantations.

This was possible because commercial bananas are all clones of each other—monocultures, in other words. Since they can’t sexually reproduce, they also can’t evolve, leaving them defenseless against disease. Within 50 years, the commercial banana crop of that era—the Gros Michel—was functionally extinct.

Fortunately for us, scientists discovered a cultivar that could resist Race 1: the Cavendish. That’s the crop we eat still today.

But history is very plainly repeating itself. Tropical Race 4 is more highly evolved than its fungal forebear, and it kills Cavendishes with ease. That threatens $11 billion global banana trade with the same sort of collapse that happened to the Gros Michel.

There’s one alarming difference, however, between now and a century ago: These days, people eat way more bananas.

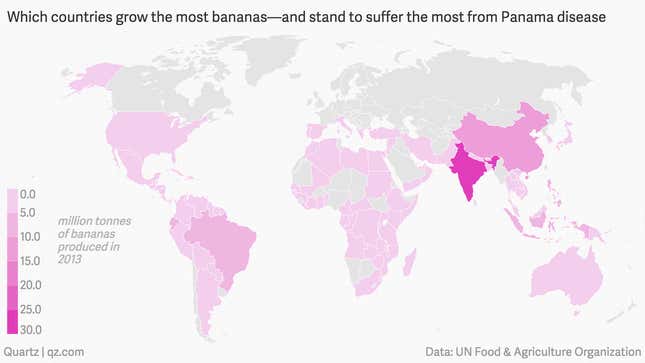

And exports are only 18% of total production. Most bananas are grown by small-time farmers in the many poor countries where they’re a staple crop. Worldwide, Tropical Race 4 is able to kill more than four-fifths of those bananas poor farming communities rely on for food. The strong likelihood that the virulent fungus will spread further the Middle East, South Asia, and Africa puts an additional 40% of global banana production at risk.

The lead image is by Ian Ransley via Flickr (licensed under CC-BY-2.0; image has been cropped). The in-text image is by Carl Drougge via Flickr (licensed under CC-BY-SA 2.0; image has been cropped).