Taking a round-trip flight from New York to San Francisco means you’re generating the global warming equivalent of two to three tons of carbon dioxide. That’s a lot—as much as a third of the total CO2 emissions created by the average European each year, and about 15% of that created by the average American. But because most air travel is done by only a tiny percentage of people, air travel only generates around 2% to 5% of total global carbon emissions each year.

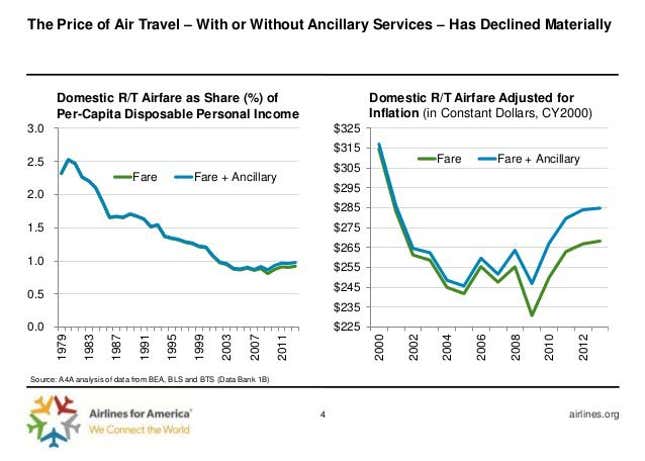

That’s changing fast. By 2017, worldwide passenger numbers will surge by more than 30% over 2012’s number, an addition of 930 million additional passengers, according to the International Air Transport Association (IATA). This is thanks to steady declines in ticket prices: Domestic US flights fell 1.3% each year between 1979 and 2012, and international airfare prices have shed 0.5% per year between 1990 and 2012.

Can the global airline industry slash its CO2 emissions fast enough to offset this rise?

Probably not—or at least not unless regulators force it to, as engineers from the University of Southampton argue in a recent article (paywall). To stop generating additional carbon by discouraging flying and keeping the number of passengers the same, the paper argues, ticket prices would have to rise 1.4% each year.

That doesn’t sound like a lot. Given that the average international air ticket bought in the US costs $1,235, a change from a 0.5% price decline to a 1.4% increase amounts to less than $25. But it adds up. By 2017, the differential would be almost $120.

Still, ticket prices are unlikely to rise on their own, conclude the researchers. Not only will the airline industry and many national governments resist any move to suppress demand, but the budget airline boom—a result of deregulation—is forcing down prices and encouraging leisure travel. A recent study found that when US budget carriers such as JetBlue, Spirit, Frontier, Alaska and Southwest launch new routes, they drive down prices charged by all carriers by as much as 67%.

So, with prices plummeting and flights increasing, the major way to put the lid on CO2 emissions is by increasing efficiency. The fact that fuel costs account for at least a fifth of carriers’ operation costs means it’s also in their interests to use less fuel per passenger. The industry has done a bang-up job in recent decades, making aircrafts more fuel efficient and packing in more passengers per plane. But it’s getting harder to produce fuel-efficiency gains at the same pace.

And beyond profit margins, there’s no real incentive for the commercial air travel industry to change anything. The International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO), the body overseeing the industry, has set targets, including fuel efficiency improvements of 2% a year and keeping net CO2 emissions at the same level from 2020 onward. However, ICAO doesn’t have any legal authority over this aspect of the industry—and neither does any other body.

What’s needed, conclude the researchers, is a global regulator “with teeth.” And history would suggest that’s hard—if not impossible—to achieve.