/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/32768393/87223414.0.jpg)

If you've looked around a city lately, you might've noticed that many cyclists don't obey some traffic laws. They roll through stop signs, instead of coming to a complete stop, and brazenly ride through red lights if there aren't any cars coming.

Cyclists reading this might be nodding guiltily in recognition of their own behavior. Drivers might be angrily remembering the last biker they saw flout the law, wondering when traffic police will finally crack down and assign some tickets.

But the cyclists are probably in the right here. While it's obviously reckless for them to blow through an intersection when they don't have the right of way, research and common sense say that slowly rolling through a stop sign on a bike shouldn't be illegal in the first place.

Some places in the US already allow cyclists to treat stop signs as yields, and red lights as stop signs, and these rules are no more dangerous — and perhaps even a little safer — than the status quo.

This is called the "Idaho stop"

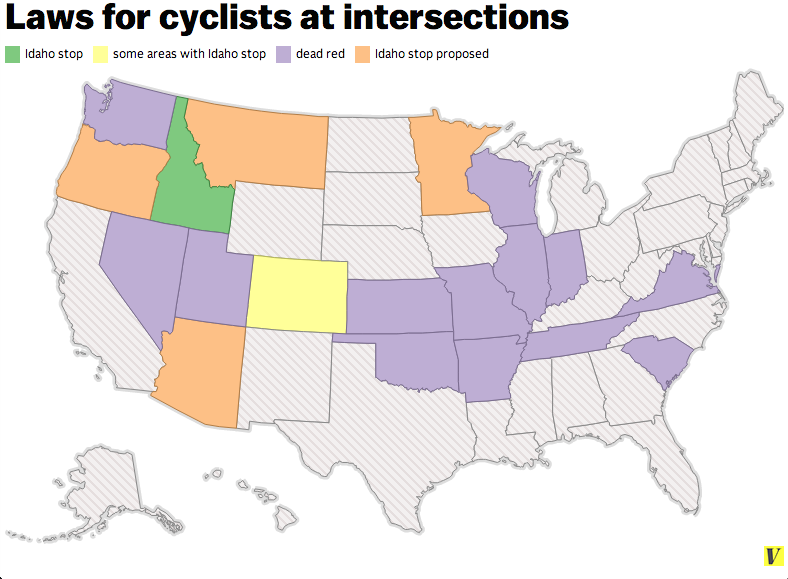

There are already a few places in the US that allow cyclists some flexibility in dealing with stop signs and red lights. Idaho has permitted it since 1982, which is why this behavior is known as the Idaho stop.

Idaho's rule is pretty straightforward. If a cyclist approaches a stop sign, he or she needs to slow down and look for traffic. If there's already a pedestrian, car, or another bike there, then the other vehicle has the right of way. If there's no traffic, however, the cyclist can slowly proceed. Basically, for bikers, a stop sign is a yield sign.

If a cyclist approaches a red light, meanwhile, he or she needs to stop fully. Again, if there's any oncoming traffic or a pedestrian, it has the right of way. If there's not, the cyclist can proceed cautiously through the intersection. Put simply, red light is a stop sign.

This doesn't mean that a cyclist is allowed to blast through an intersection at full speed — which is dangerous for pedestrians, the cyclist, and pretty much everyone involved. This isn't allowed in Idaho, and it's a terrible idea everywhere.

This video, produced when Oregon was considering a similar law in 2009, has some nice visualizations of the Idaho stop at around one minute in:

Apart from Idaho, this is the law in a few Colorado cities (Dillon, Breckenridge, and Aspen).

Several states have similar "Dead Red" laws, which lets cyclists (and motorcyclists) ride through a red light if there's no traffic, if the cyclists have stopped for set periods of time, and if the light isn't changing because its sensor doesn't register bikes.

Proposals to allow the Idaho stop have been proposed in a few other states, but they haven't been approved.

Why so many cyclists do this illegally already

So many cyclists do these things on their own — without even knowing they're enshrined in law anywhere — because they make sense, in terms of the energy expended by a cyclist as he or she rides.

Unlike a car, getting a bike started from a standstill requires a lot of energy from the rider. Once it's going, the bike's own momentum carries it forward, so it requires much less energy.

In 2001, physics professor Joel Fajans conducted tests on California Street in Berkeley — an official bike route with tons of stop signs — and found he was able to maintain an average speed of 10.9 miles per hour without breaking a sweat. On a parallel street without stop signs, he could cruise about 30 percent faster — 14.2 miles per hour — with the same amount of energy.

He also calculated that a cyclist who rolls through a stop at five miles per hour instead of stopping fully needs to use 25 percent less energy to get back to full speed.

This explains why many cyclists roll through stop signs so often. Of course, the simple fact that people often do something that's against the law doesn't mean the law should be changed — but here are a few reasons why it really should:

The Idaho stop isn't more dangerous — and might even be safer

Spencer Platt/Getty Images

For drivers, the idea of cyclists rolling through an intersection without fully stopping might sound dangerous — but because of their slower speed and wider field of vision (compared to cars), cyclists are generally able to assess whether there's oncoming traffic and make the right decision. Even law-abiding urban bikers already do this all the time: because of the worry that cars might not see a bike, cyclists habitually scan for oncoming traffic even at intersections where they don't have a stop sign so they can brake at the last second just in case.

There are even a few reasons why the Idaho stop might even make the roads safer than the status quo. In many cities, the low-traffic routes that are safer for bikes are the kinds of roads with many stop signs. Currently, some cyclists avoid these routes and take faster, higher-traffic streets. If the Idaho stop were legalized, it'd get cyclists off these faster streets and funnel the bikes on to safer, slower roads.

The Idaho stop, if legalized and widely adopted, would also make bikes more predictable. Currently, when a bike and a car both pull up to a four-way stop, an awkward dance often ensues. Even when cars get there first, drivers often try to give bikers the right-of-way, perhaps because they think the cyclist is going to ride through anyway.

If the cyclist logically waits, both parties end up sitting there, urging the other to go on. In the opposite (and rarer) scenario, both people assume the other will wait, leading to a totally unnecessary accident.

An Idaho stop would put an end to this madness: the first vehicle to come to the intersection always has the right of way, giving bikers a rule they'd actually follow, making them more predictable for drivers.

If all this sounds far-fetched to you, look at the data. Public health researcher Jason Meggs found that after Idaho started allowing bikers to do this in 1982, injuries resulting from bicycle accidents dropped. When he compared recent census data from Boise to Bakersfield and Sacramento, California — relatively similar-sized cities with comparable percentages of bikers, topographies, precipitation patterns, and street layouts — he found that Sacramento had 30.5 percent more accidents per bike commuter and Bakersfield had 150 percent more.

Stop signs and traffic lights weren't designed for cyclists

Tim Graham/Getty Images

Cars are 2,000 pound-plus machines that, on most roads, travel at 30 miles per hour or faster. In most cases, a driver can't safely decelerate from this speed to yield to oncoming traffic at an intersection without coming to a full stop first.

Because of the dangers posed by cars, stop signs and traffic lights were invented in the early 20th century to bring order to roads increasingly filled with them. Nowadays, stops signs are often used not only to make intersections safe, but to slow down traffic in residential areas.

Bikes are different — they don't go fast enough to merit this sort of traffic calming, and don't have a problem just slowing down for an four-way stop, only stopping if a car's coming. Oftentimes, they don't trigger traffic lights to change, because many run on inductive sensors buried in the road (the reason for all the "Dead Red" laws in the map above).

Some cyclists oppose the Idaho stop because of an idea they believe is central to gaining respect for cycling and encouraging good relations with drivers: "same road, same rules." Because both bikes and cars are wheeled vehicles that use roads, the principle goes, they should always abide by all of the same rules.

This sounds great, in theory, but it doesn't describe the reality of current traffic laws. Most interstate highways don't allow bicycles, for instance. Many cities have bike lanes that cars can't enter. They're clearly two different sorts of vehicles, and we have rules that apply to one but not the other.

Consider another group of road users that stop signs weren't designed for: pedestrians. Like bikes, pedestrians don't need to come to a complete stop to avoid accidents at intersections, which is why you don't see them weirdly freezing in place when they arrive at one. In most areas, skateboarders, Segway riders, inline skaters, and people in electric wheelchairs aren't required to stop at stop signs either.

Ultimately, a cyclist occupies a space somewhere in between a pedestrian and a car (faster and more dangerous to others than the former, but smaller and slower than the latter), so the laws that apply to bikes should be somewhere in between — exactly like the Idaho stop.

Laws that serve no purpose (and aren't followed) shouldn't exist

This is a principle that's frequently brought up in support of marijuana legalization, and it's relevant here as well.

Given that this behavior is common among cyclists, the current laws mainly criminalize something strongly associated with cycling. This might even enflame drivers' resentment of bikers more than if by rolling through stop signs, they weren't breaking the law. The laws also divert police from cutting down on actual unsafe biking behavior — like the jerks who fly through intersections at full speed when they don't have the right of way.

We even have precedent for a logical, forward-thinking regional movement to ease restrictive traffic laws going nationwide. In 1947, California became the first state to allow drivers to make a right turn on red. During the 1970s, when gasoline prices skyrocketed, dozens of states adopted similar laws, largely because of Federal Highway Administration findings that it saved a lot of gas.

In an era when lots of towns and cities are actively trying to get more people biking — to reduce traffic, if not carbon emissions — you'd think they'd want to remove any hurdles to biking that don't need to be in place.

So let's do it. Let's follow Idaho.

Correction: This piece previously stated that most lights run on weight and magnetic sensors, not inductive sensors. The map also previously showed some states with "Dead Red" laws that only apply to motorcycles, not bikes.