Nine years ago, when Graham MacIndoe was living in New York City and addicted to heroin, he started collecting the small glassine bags that held the drugs he bought. MacIndoe was a commercial photographer, and even in the grip of a years-long addiction that would ultimately leave him broke, imprisoned on Riker’s Island, and facing deportation, he became interested in the baggies on a visual level.

“There was just something about the design, the typography, the branding,” MacIndoe tells Quartz. “And just being around the drug trade myself, the promises that were in the bags—of good times and money, and this elusive lifestyle that you thought drugs would bring you.”

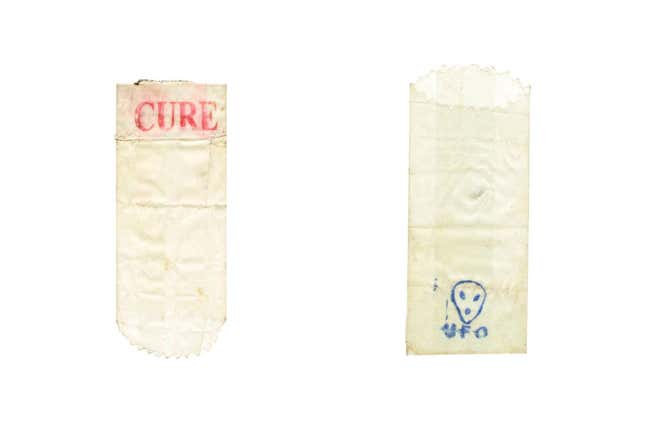

The bags (bought in bulk from jewelry stores) announced different strains of heroin with hand-stamped logos, like cruder versions of the products that pander for your attention from shelves and billboards. And they used techniques that can be found in any corporate branding project: promises of quality (Extra Strength, Uncut), pop culture references (Twilight, O.D.B.), and black humor (Kiss of Death, Undertaker). “It’s very cleverly marketed by people high up in the drug trade,” MacIndoe says. “They come up with these quirky names.” (The names also serve a practical purpose, allowing someone looking for heroin to avoid incriminating himself to an undercover cop.)

MacIndoe found that marketing in the underground economy mirrored the corporate one in other ways. Special offers often accompanied a new drug’s introduction. Popular brands quickly attracted imitators, who adopted the visual look of the packaging but filled it with a lower-quality product. A kind of built-in obsolescence was common too, with suppliers “cutting” (i.e., adulterating) initially potent brands to maximize profits—a pressure to upgrade that MacIndoe compares to Apple’s strategy with the iPhone. “They’re giving you a product that seems really great at the time,” he says, “and then after a little while you realize you’ve got to move on, because they’re telling you something else is better—and they’re making it better intentionally so you’ll move on to a different brand.”

Now in recovery, MacIndoe has put together a book of photographs of the baggies, All In: Buying Into the Drug Trade, which will be published later this month through Little Big Man. In the book, each bag is shot on a glaring white background, like an Apple ad, to reinforce his argument that these are consumer products too. After all, MacIndoe seems to be saying, the drug trade may be a black market, but it’s still a market.