The Joy of Exercising in Moderation

I hated exercise—until I learned you don't have to be intense about it.

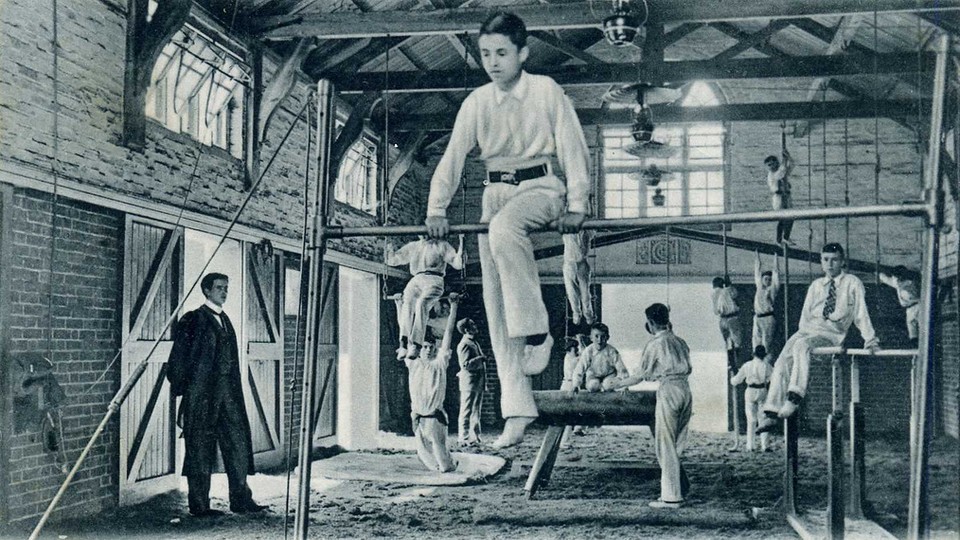

I wonder sometimes if I was born hating exercise. Ever since I had to climb the rope in second-grade gym class, I regarded physical activity with confusion and fear.

“Up you go,” said my gym teacher, an older man named Mr. Baylake, who wore green knee socks and had a drill sergeant’s voice. He pointed at the rope and nodded his head as if we would know exactly what to do. It stretched high into the rafters, and as I craned my neck heavenward, I wondered how someone had initially got it up there. I certainly didn’t want to climb the thing, and was sure the other kids felt the same. That is, until those other kids, not necessarily skinnier or stronger than me, began shimmying up one by one. None made it close to the top, but each figured out how to gain at least a meter before sliding back down with smug looks of achievement. It seemed so easy for them, so intuitive.

When my turn came, I grabbed ahold, leaned back and, with a sad little grunt, was barely able to bring my feet off the ground. I did this a few times, but mostly just dangled, creaking back and forth as other students snickered. A clownish display until Mr. Baylake took mercy and said, “Okay, kid. That’s enough.”

It’s not that I hated the idea of being physical. I became mildly interested in tae kwon do after my eighth birthday and—obsessed with the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles—harbored the idea that if I could only get my hands on a pair of traditional Japanese sais, I would make an excellent ninja. When it came down to the playing field, however—court, rink, or mat—I always drifted toward the sidelines.

During my final year of little league baseball, the coach, understanding how hopeless I was, gave me a “special position” beyond left field, way back out by the fence (actually, it was the fence). Oblivious, thinking I’d been given carte blanche, I’d lean up against a post and stare at the clouds, completely caught by surprise when the bat cracked a long drive, the ball flew toward me, and parents started screaming from the bleachers. I even brought a book out there with me once, taking it out of my back pocket and reading as the game went on.

Maybe it’s just the competition angle of exercise that’s always pushed me away, being that I was raised by someone who valued rivalry above all else. My father bench pressed 450 pounds three times a week. If there was sun in the Colorado sky, he was outside in electric blue spandex shorts and matching flip-flops, sucking up rays until his skin turned the color of French toast.

He was the kind of guy who looked at the world like I imagined early man gazed upon the advent of fire. Reality was perilous, and the only way he could fight back was to turn his body into a suit of armor. I’d seen him pull a man through a car window at a stoplight after the man cut him off in traffic. I’d seen him slam the heads of those who wronged him into walls and run after doorbell-ditchers like a blood-crazed animal.

I, on the other hand, drew pictures of dragons, wizards, and popular anime characters. As a young boy I liked Rainbow Bright, My Little Pony, Care Bears, and Thundercats. I read fantasy novels and collected comic books that depicted men and women who were preternaturally strong not because they worked out, but because they’d been exposed to gamma radiation or came from an alien world. I was pigeon toed. I had (and still have) a disproportionately long torso for the size of my legs. I have terrible depth perception and a low pain threshold.

None of that really made sense to the man who raised me. He shamed me into weekend trips to the gym, poking at my chubby, 13-year-old stomach and reciting gems of wisdom like, “If you don’t start working out now you’ll have diabetes when you’re 16.”

The smells that swirl around your average suburban health club are equally rancid and anodyne. Men and women (but mostly men) dominate the weight room, crawling under the skeletons of medieval-looking machines. An eau du inadequacy permeates every inch of sweaty air. Though there are certainly exceptions, the majority of gyms in this country aren’t places where you go to feel good about yourself. They’re places where you go to be shamed into self-improvement. There’s someone always fitter than you working on his deltoids, who grunts louder than you, and whose veins bulge out farther.

And there I’d be on a Saturday morning, standing flabby-armed beside my muscle-bound father, feeling a combination of bored, angry, and scared as he adjusted the weights. Though I didn’t start going to the gym with him until I was a teenager, with a role model like mine how could I help not internalizing ineptitude early on? When you live in the same house as Goliath, you either become David, or you become utterly crushed.

Humans are built to consume and burn. Fuel is expended through energy, and inertia signals the onset of death. So then perhaps it’s not entirely true that I was born hating exercise; I was just born to a man, like a lot of men, who loved exercise too much. A man who was afraid of old age, and whose ideal of perfection was beyond what I could achieve.

Our country champions a “do or die” mentality. Just as we’re the nation of hotdog eating contests, Spike TV and demolition derbies, so are we the nation of CrossFit, Tough Mudder, and other rigorous forms of self-maximization that—to the rest of the world, at least—makes us seem like a bunch of creatine-jacked masochists. Extreme exercise and extreme eating influence each other, leaving little room to explore moderation between the two. Just as my father gave himself two hernias lifting at the gym, he also battled with compulsive eating all his life.

Cartons of Costco muffins would disappear in an afternoon. Half-gallons of ice cream and liters of chocolate milk would be gobbled down in minutes. Then I’d hear him plowing away at his stationary bicycle into the night, lifting and groaning for hours on end. For him, exercise and food were always at war. Any truce between the two was unimaginable. And as for me, I just embraced the food angle and eschewed exercise completely. Neither of us have a history of good bodily decisions.

When my wife became a personal trainer, I naturally experienced a profound sense of dread. The two of us met in a Fiction MFA program in graduate school, and both come from creative backgrounds. I was an aspiring novelist; she, a talented writer and editor. She loved food just as much as I did, and was typically game for weekend-long television marathons; when we married, I never thought her love of fitness classes would turn her (and thus, me) toward the path of Lululemon and muscle shirts.

It wasn’t that I feared she would push me to join her at the gym. I just couldn’t understand how she was able to even enter one without embracing the same code of conduct I’d witnessed in my father and those like him throughout my life. Whenever I thought of exercising, I thought about all the years of not measuring up–of having poor balance and being mocked by the strong. How could my wife join the ranks of those I considered my archenemies?

It took a while for me to understand, however, that more than anything I had become my own enemy. Sure, there are a lot of people who treat self-improvement like they’re trying to survive a zombie apocalypse. But there are also people who can’t seem to see the positive effects of physicality on a daily basis. My outlook in particular began to change when my wife–after months of subtle cajoling–got me to attend a yoga-like/Pilates/stretch class with her at a studio near our Bay Area home.

I was skeptical, thinking I’d have to put up with some more thick-necked men with sweat-glistened chests, snorting nostrils, and mocking stares. But instead, I saw people who were awkward like me, trying to find their balance, even recovering from injuries. The class itself was led by a woman who approached the body intellectually and with a sense of discovery.

For my wife, exercise wasn’t about competition. It was about what makes you feel better. After the class I took with her, as opposed to feeling repulsed, I realized that my body had been asking me to treat it better for a long, long time. I also came to understand that I wasn’t the only person with insecurities when it came to physical activity. Everyone in the class had imperfect postures, oddly shaped bodies and off-kilter balance. The feeling for me was liberating to such an extent that I continued to go back—sometimes by myself.

I graduated from there to yoga, occasional bike riding, and a commitment to walking at least three miles a day. At one point I even took a spin class. It was taught by a female version of my father, decked out in fire-red Capri pants, and the class itself, ensconced in a room full of mirrors and neon lighting, made me feel like I was inside some horrific combination of a Euro-discotheque and The Hunger Games.

It wasn’t a wholly pleasant experience, but it was a choice I made on my own, and which led me to awaken to other forms of self-maintenance. Now I’m even considering taking up aikido and flirting, distantly, with the idea of half marathons.

Recently, my father turned 60. My wife and I went out with him to dinner, and he showed up in an opalescent white suit. He’s a lot less intense of a man than he was in his youth. He eats smaller portions of food. He plays tennis three days a week and talks more quietly. He even asks my wife questions about fitness—knowing, perhaps, that he’s missed something along the way. Sometimes he’ll tell me things like, “You’ve lost weight,” even if I haven’t. Other times he’ll just say, “You look good.”

Though I’m not totally comfortable admitting it, his compliments strike a chord.

I never thought I’d be searching for acknowledgment in the energy-jacked world I’ve been running from all my life. But I’ve come to realize that as a young boy, all I needed to be told was that there were different ways to move; ways that weren’t worse just because they weren’t competitive. I needed to hear that being fit isn’t always a contest, that in many cases it’s anything but. If I could go back to tell that kid in second-grade gym class one thing, it would be that it’s okay not to want to climb the rope. That someday you’ll be able to decide for yourself, with both feet planted firmly on the ground.