The Latin American experience suggests primary elections can be effective but not a magic recipe for party democratisation

Both Labour and the Conservatives have been experimenting with primary elections to select candidates, as a means of reconnecting their parties with the electorate at a time of diminishing membership levels. There are lessons to be learned from countries around the world that use primaries. In this post, Flavia Freidenberg and Julia Pomares discuss the experience of Latin America, where a range of different systems for candidate selection are in place.

The United States and Argentine presidents Barack Obama and Cristina Fernández were both selected by their parties in primary elections before facing the electorate for a second time at a general election. Credit: Casa Rosada, CC BY-SA 2.0

A recent op-ed published in the New York Times presented a controversial argument: the chief American victory in exporting democracy is not to be found in the Middle East but rather in the near West, in the shape of the promotion of primaries as the main mechanism for political candidate selection in Latin America and Europe.

The great variation in design of candidate selection processes across Latin America seems to be at odds with a mirroring of the American experience. Interestingly, Latin Americans did export the term ‘primaries’ but no Latin American country conducts primaries in the American way. In any case, there is no doubt that the use of internal elections as a method for presidential candidate nomination has risen dramatically, with almost 60 internal electoral processes in the last 20 years in Latin America. These experiences are increasingly a source of debate among the region’s politicians, academics and media.

Against a background of sharp decline in party legitimacy, frequent party infighting and increased party fragmentation in Latin America, internal elections emerged as a magical recipe for party reform in several countries of the region. They soon evolved into“ the Queen of party modernization reforms”. As such, they have been asked to deliver several – and sometimes competing – goals: promoting intra-party democracy, solving conflicts between party factions, strengthening party links with society and institutionalizing party systems and electoral coalitions.

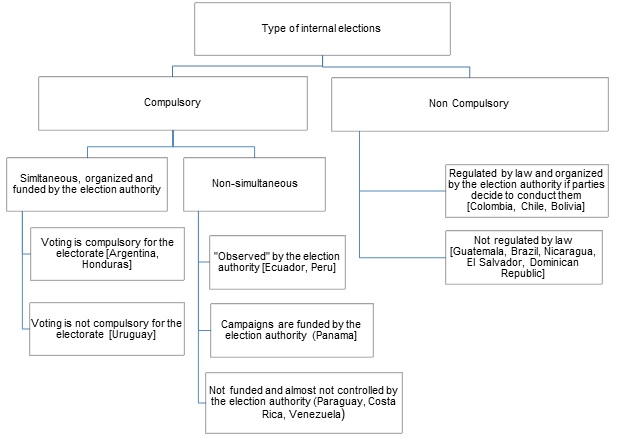

What lessons can we learn from their extensive use in Latin America over almost two decades? Today, thirteen Latin American countries have legislation allowing for internal competition for presidential candidate nomination. In eleven, the reform took place as of the mid-nineties. But there is no one model fitting all countries. Variation in the design of the candidate selection mechanism can be seen across three main dimensions (see chart below).

Types of internal elections in Latin America

Note: Mexico is not included here because it is currently under reform.

The first has to do with the obligatory nature of the mechanism: whereas some countries impose primaries on political parties as the only method for selecting their candidates, others regulate its implementation but give parties the option not to use it. Costa Rica is the country with the longest tradition of compulsory internal elections (1949), but it relaxed the system in 2010. Uruguay introduced compulsory primaries in 1996 to replace the double simultaneous vote (an electoral system in which the internal election is simultaneous with the general one, in place since 1922) and Argentina followed suit in 2009 after a failed attempt at reform in 2002. In Argentina, primaries are not only compulsory for parties but also for voters (applying the same penalties on non-voters as in general elections).

The second dimension relates to the date of the election – whether it is simultaneous for all parties or not. The idea behind having all parties select candidates on the same day has more to do with strategic partisan considerations than concerns about money. Some party leaders fear that the members of other parties will vote for candidates that most suit their own strategic ends. Only in three countries (Argentina, Uruguay and Honduras) are primaries held simultaneously.

The third dimension relates to who is entitled to participate in the internal election; ranging from only party members – closed elections – (Ecuador, Mexico, Panama, Honduras) to the whole electorate (Argentina). The debate over the size of the electorate is an important one. When the internal election is open to the whole electorate, the dispute over internal problems is transferred to the electorate at large and, on some occasions, intense disputes among candidates arise during the general election campaign. When the internal election is open to independents but party member registers are not reliable (as in many Latin American countries), it is more likely that members of one party intervene in other parties’ internal elections.

What conclusions can we draw from the extensive use of primaries in Latin American countries? We posit three here:

- In several countries, internal elections have fared better at reinforcing parties’ leaders than strengthening parties’ roots, having failed to contribute to intra-party democracy. In cases like Mexico or Panama, elections have tended to be non-competitive and candidates selected by internal elections have not been the most competent in the eyes of the electorate;

- Although difficult to measure empirically, party leaders in several countries perceive that the use of internal elections to nominate candidates has not led to an electoral advantage. In those countries (Dominican Republic, Mexico, Panama or Ecuador, for example), strong opposition to internal elections has increased among senior party figures;

- Evidence from Argentina shows that simultaneous, open and compulsory primaries, conducted close to the general elections, can work as a mock first round, driving voters to behave strategically and change their electoral choices across elections.

Also, based on experiences so far, we can highlight some examples of best practice regarding the institutional design of Latin American internal elections:

- Even where internal elections are not compulsory but parties can decide to conduct them, there is a need for supervision by the election authority and for a legal framework (such as in Colombia, Bolivia and Chile);

- A reliable register of party members is a key pre-requisite for any type of internal election, in particular when the internal election is funded by the state (like Mexico);

- Results of internal elections should be binding (Chile) and parties should be penalized if they register and field candidates other than those winning those internal elections.

The Latin American experience shows that internal elections can be a useful tool for promoting party democratization if they are carried out in favourable conditions: when reforms take place in contexts where there are strong incentives to adhere to them, the chances of primaries being successful increase dramatically.

—

Note: This post represents the views of the author and does not give the position of Democratic or LSE. Please read our comments policy before responding. Shortlink for this post: buff.ly/1j1B3u5

—

Flavia Freidenberg is Director of the Instituto de Iberoamérica (Salamanca University, Spain)and professor of political science and public administration at the same university. She holds a PhD in Political Science and Latin American Studies from Salamanca too. She specialises in internal democracy and strengthening of political parties, quality of electoral process, women’ representation and clientelism. She is currently working on a project on the effectiveness of gender quotas in sub-national legislatures in Argentina and Mexico. Her work has been published in Latin American Politics and Society, LASA Forum and in renowned peer-reviewed journals in Chile, Mexico, Spain and Argentina (such as Revista de Ciencia Política, Política y gobierno, Revista de Estudios Politicos and DesarrolloEconómico). View her publications here, or find her on Twitter @flaviafrei.

Julia Pomares is the Director of the Program on Political Institutions at CIPPEC, the largest think tank in Argentina. Received her PhD in Political Science from the London School of Economics and holds a Masters in Comparative Politics and in Research Methods from the same university. As Director at CIPPEC, she leads the initiatives on electoral integrity and strengthening of political parties. Among the latest initiatives, she led an applied-research project on the sharp rise of incumbency advantages in Argentine provinces and an evaluation of the first e-voting election in Argentina. Her work has been published in academic journals like Electoral Studies and Political Behavior. She is now working on applications of electoral fraud forensics with Inés Levin and Michael Alvarez. She Tweets on @juliapomares.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Latin American parties use primary elections in varied ways – what is best practice? by @flaviafrei & @juliapomares https://t.co/8WAbUt6MRa

La experiencia de las elecciones primarias en #AméricaLatina ¿Qué lecciones ofrece? https://t.co/sAa1tCISVI vía @democraticaudit @flaviafrei

¿Estás de acuerdo con nuestra visión sobre las primarias en América latina? Dinos que piensas! @juliapomares https://t.co/S5WACAyzvz

I think (and Captain America would agree, that primary elections are really stupid way how to promote the internal democracy. Especially in Argentina, which was dominated by quasi-nazi Victory Front, their introduction is arguable. What sense does it have when the main party caudillos still have nominations in their hands.

The Latin America suggests primary elections can be effective but not a magic recipe for party democratisation https://t.co/8LzDm0beS8

The #LatAm experience suggests primary elections effective but not a magic recipe for party democratization. https://t.co/IPGVLBBDs2 …

RT @flaviafrei: How to run primary elections effectively: evidence from Latin America – @flavia and @juliapomares on Democratic Audit http:…

Parties using primaries to select candidates need to make sure the process is transparent, and the result is binding https://t.co/JAeiztZgYa

Primary elections must have a legal framework and be overseen by election authorities to be effective https://t.co/fEM7hCKiV9

Primaries seem to me about parties retaining control, rather than giving choice to the electorate.

Encouraging multiple candidates representing the shades of opinion within parties to stand in the actual election, combined with transferable preference voting, gives choice (and power) to the voters. ( https://wp.me/pUTZ7-48 ) It also makes the election debate about ideas rather than parties.

Too often the “majority within a party” is actually a minority within the electorate, whilst a “minority within a party” may actually have the best chance of commanding a majority from the electorate.

Interesante lo q han escrito @Juliapomares y @flaviafrei sobre las primarias en America Latina via @democraticaudit https://t.co/sShLA3hFQR“

@atullio ¡las primarias argentinas contribuyendo al debate inglés! Ahí va: https://t.co/P7IGQHvq30

¿Sirven para algo las primarias? Lo que escribimos con @flaviafrei sobre América Latina para @democraticaudit https://t.co/P7IGQHvq30

How to run primary elections effectively: evidence from Latin America – @flavia and @juliapomares on Democratic Audit https://t.co/7tihkDTcIQ

The Latin American experience suggests primary elections can be effective but not a magic recipe for… https://t.co/03fGa1CebE