A couple of weeks ago, a 19 year old girl called Yashika was removed from the UK. Her detention and subsequent return to Mauritius, without her family and just weeks before her exams, brought under public scrutiny the workings of the asylum system. This included the reality of immigration detention, the separation of families, and the forced removal of refused asylum seekers to their countries of origin.

In the pursuit of justice and compassion for this bright, integrated and well-liked young woman, Yashika’s supporters posed many questions to which they are yet to find satisfactory answers. Doesn’t her life here count for anything? What about her education and her friends? Surely the fact that 183,000 people have signed a petition should make a difference? Is it really ok to separate a teenager from her family and return her to a potentially unsafe environment?

Yet in spite of the questions and protests, Yashika has gone.

Some of issues raised by Yashika’s situation are flagged up in last week’s well-timed and well-named report by the Office of the Children’s Commissioner: What's going to happen tomorrow?": Unaccompanied children refused asylum. Like Yashika, and the many known to me personally, everyone who claims asylum in the UK ‘deserves a future’, whether that future lies in the UK, their country of origin or somewhere else entirely.

This tragic situation faced by Yashika, suggests Owen Jones, has nevertheless brought glimmers of hope. He ends a thoughtful article by asserting that “the case of Yashika humanises a broken and cruel system, and appeals to a sense of justice that most people do have. For those of us who want a different sort of debate about immigration, it should encourage us to give a platform to other voices, too.”

We must use this window to bring different voices into the immigration debate and to tackle head on some of the difficult questions that have been raised.

Law or compassion?

For many, Yashika’s removal from the UK was shameful and cruel, yet for others it was vital for upholding the sacred principle and practice of asylum. According to some commentators, as tragic as her situation was, her asylum claim simply did not have a legitimate basis and she had to go.

Given how reluctant the UK was to offer sanctuary to even a tiny number Syrians, we must ensure that we have keep in place as many protection frameworks as possible. But Yashika’s case has flagged up, yet again, their limitations.

Leaving to one side the nuances about what it means to be a refugee and the fact that the current determination process leaves much to be desired, what Yashika’s story highlights primarily is the way that protection issues in the country of origin often need to be seen alongside those factors which contribute to a person’s safety and wellbeing in the UK. As the campaign for her to stay suggested, yes, she had been escaping ‘abuse and danger’ in Mauritius but she had also built up a life, safety net, community and future here. Those things mattered too.

There’s something intuitive in Yashika’s supporters’ recognition of people’s need for a multifaceted life of flourishing, not just a physical life of non-death. This recognition is arguably particularly crucial for those who come to the UK as unaccompanied asylum-seeking children and spend their formative teenage years in British culture and society. However, recent legal aid cuts have made it increasingly challenging for these young people to access the legal frameworks which would protect these aspects of their lives.

‘Emotional autopilot’ or mercy?

Like the 183,000 who signed the petition for Yashika to stay in the UK, I wish that the UK government had shown compassion rather than simply ‘engaging emotional autopilot' so that Yashika could have completed her exams. As her school principle said: “I just cannot believe they would send her back six weeks from her exams. Why can't there just be some compassion and humanity to allow her to stay and do those A-Levels?” It made no sense for her to leave without the qualifications that could have facilitated her educational progression and put her in a stronger position to face multiple possible futures. For where the law condemns or where access to it is denied, calls for compassion and mercy emerge.

What I also wish is that Yashika's story would encourage us to call for compassion for other unseen young people from asylum-seeking backgrounds who come up against blanket rules which inhibit their educational progression and general thriving on a daily basis; for example, those which prevent young asylum seekers from participating in higher education. I’ve been wondering if a bit more compassion in other parts of the system could have led to a less tragic outcome for 19 year old A level student Nida Naseer who had been refused asylum, and whose body was found earlier this year. As a BBC article reports: “Family members say she was depressed before she went missing and believe she disappeared because the family's asylum-seeker status prevented her from attending university”.

Is it really ok to detain and forcibly remove a teenager?

In addition to sparking debates about the law and compassion, what Yashika's situation also revealed was the stark reality of immigration detention and forced removal. My friends' shock at the fact that a teenager could be separated from her family, locked up, then sent back alone to her country of origin, made me realise how normal certain horrific realities have become for me through years of working with unaccompanied asylum-seeking children in the UK.

Sadly, what came as a surprise to Yashika and her supporters – the fact that the immigration system draws a stark line between children and adults and it really matters which side of 18 you fall – is something I’ve almost got used through watching numerous young people transition overnight from ‘looked-after children’ to ‘adult refused asylum seeker’, to their detriment. And Yashika is not the first teenager who has been unable to prove her need for refugee status and who has – in spite of ongoing protection needs, vulnerability, life in the UK, and aspirations for the future – been forcibly removed. In the past 5 years, over 500 young people who came as unaccompanied minors have been sent back to their countries of origin and many others, like this young blogger, face extended periods of uncertain limbo. That’s 10 coach loads of students gone awry on a fieldtrip. Or almost 50 exiled football or netball teams.

In Yashika’s case, the government of Mauritius has given assurances of her safety. I truly hope that this comes good and that she isn't harmed on return in spite of the threats to the contrary. Sadly, the outcomes of other young people who are removed from the UK to volatile contexts like Afghanistan, on overnight charter flights and out of the public eye, lack the follow up scrutiny that her case is likely to attract, and no one really knows what happens to them on return.

On a recent visit to Kabul, we met up with some young returnees and began to gather much-needed evidence about their outcomes post-return and to document their realities. The stories of young people like Abdullah and Mohammed get less airtime, but need nevertheless to be told. Small details reveal the poignancy of these rigid transitions. For Rahim, forcibly removed from the UK one year ago, braces fitted in the UK have become almost as big an issue as his lack of employment and secure housing. In Kabul he is unable to get them tweaked and refitted as intended, and as a result, he has tried to remove them himself.

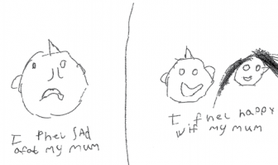

Photo: Refugee Support Network

What now for Yashika and for us?

I would hate it if the academic and political debates provoked by Yashika’s well publicised case obscured the reality of her life and story as a young woman who has recently undergone a significantly traumatic ordeal and will undoubtedly face many challenges in the months to come.

While Yashika’s multifaceted life here didn’t count for much in terms of her asylum claim, I hope at least that she has returned to Mauritius confident that she is known and loved and has people on her side. I hope too that those who recognised that she was not merely a 'refused asylum seeker' or 'overstayer', but a student, friend and classmate, will remember to avoid over simplistic labels in the future when referring to those who are not known to them personally. When phrases like 'bogus asylum seeker', 'genuine refugee', and those who are 'just here for a better life' are batted around in the media, may we be quick to question their assumptions, see beyond the labels and reclaim a language that humanises migrants.

As those who were fortunate enough to be born in a safe and affluent society, we have a responsibility towards these teenagers; to not only to show compassion in our language and actions, but to pursue justice through fairer systems and processes which will contribute to their long-term safety and flourishing. This is not the end of #FightforYashika

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.