The overwhelming message from the media today is that a woman’s body parts mean more than she does, say Holly Baxter and Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett, founders of the blog, The Vagenda, and now the book of the same name.

And good for them. Women’s magazines do that and a lot more besides. They reduce all challenges in society to the problems and neurosis of the individual. It’s not the system that’s at fault, it’s me. If only I was thinner, prettier, less mottled in the leg, then I could really do something about the growing mountain of food banks/inequality/Syria.

Magazines extract the protestor’s nerve because there is more money to be made if a woman stands alone and vulnerable, searching for private solutions, when the real concern is the profound structural flaws in the public domain that can be defeated by collective action.

Magazines also reinforce the role or roles that a woman is expected to play. In the 1950s, it was the good mother, the attentive wife. Today's woman, as depicted in the glossies, is allegedly orgasmic a great deal of the time when not pursuing personal physical (and sometimes spiritual) perfection but to the satisfaction of whom is pretty muddy – men, other women, the boss, A higher being?

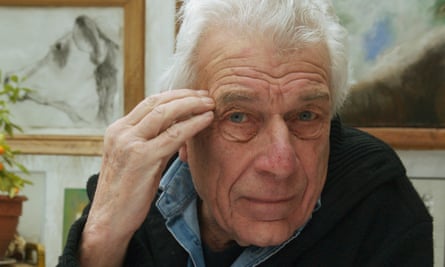

What we know well is that there are hidden ideologies in visual images; every picture counts whether mundane or iconic. That has to be at the heart of Baxter and Cosslett’s thesis because it’s where the power of the women’s media lies, in the Look. As John Berger argued so eloquently in Ways of Seeing, deciphering the look is a political act with huge potential clout.

He explained how the owners of the European classic nude painting were usually men, and the women were generally portrayed on canvas as stripped of pubic hair that was deemed too threatening, too unfeminine. They were objects, proof of an art collector’s power.

“The unequal relationship is so deeply embedded in our culture that it still structures the consciousness of many women," Berger wrote in the 1970s. “They do to themselves what men do to them. They survey, like men, their own femininity."

It’s ironic then, if every picture tells a story, that Baxter and Cosslett are pictured in The Guardian, each with her hand on her hip. Is this the direction of the photographer? Their instinctive choice? Or does it also reveal how deeply embedded is that unequal relationship of the active male viewer and the passive object of his attention?

Given the strength of their feminist beliefs, it’s unlikely the two campaigners realised, that what they are semaphoring is the classic pose of the “look-at-me” beauty queen; the unnatural strut of every woman on display for the pleasure of the male eye. The question is, does it matter?

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion