Most US airlines follow the same procedure for allowing non-first-class passengers to board a plane. They let people who are sitting in the back board first, then people in the next few rows, gradually working their way toward the front.

This procedure makes absolutely no sense.

If asked to devise a boarding method without any data, you might settle on this as a pretty sensible one. But the airlines do have data — and numerous studies have shown this is not a good way to board an airplane, in terms of time or customer satisfaction.

The fastest ways to board a plane are Southwest's boarding method — where people choose their own seats — or a theoretical boarding method known as the "Steffen method" that's not currently in use.

Both simulations and real-life experiments have proven the standard method to be the slowest out of several different ones. In 2012, the TV show Mythbusters recruited 173 people to compare four methods in a replica airplane interior and found that Southwest's boarding method was the fastest. A close second was allowing all windows seats to board first, then all middles, then all aisles (outside-in).

The worst way to board a plane

Here's a video showing the standard boarding process, used by the vast majority of airlines:

You can see the problem with this process pretty clearly in the video: People spend a lot of time waiting in line in the aisle.

That's because when each passenger goes to sit, there's a good chance someone who's already seated in that row will have to get up to let him or her in, slowing everything down (the only way this can be avoided is if they happen to arrive in window-middle-aisle order). At any given time, most of the people who are boarding are trying to access the same few rows and the same few overhead bins, so everyone has to do a lot of waiting in the aisle.

Having the back board first seems logical, but all it does is move the line onto the plane, instead of the jet bridge.

A slightly better way: the random method

Surprisingly, just letting people get on the plane in an order unrelated to their seats leads to slightly faster boarding times than the standard method.

US Airways began doing this in May 2009: It let frequent fliers and the like board first, then everyone else, by order of check-in.

This method is a bit faster because at any given time, most of the people boarding the plane are not trying to get in the same few rows and overhead bins at once. There's still some congestion — because of people needing to get up to let others in — but it's staggered throughout the plane.

An even better way: the outside-in method

Having everyone with window seats board first, regardless of row, then all people with middle seats, then all people with aisle seats is much faster.

United Airlines switched to this method in June 2013 (although it make an exception for families, allowing them to board together).

This method cuts down on the total amount of congestion because each time a passenger sits down, no one is already sitting in their row, so they don't have to wait for someone to get up to allow them in. Because everyone isn't trying to get into the same few rows at the same time, many different passengers can access the overhead bins and enter their seats simultaneously.

The small downside is that people who are sitting together can't board together, a problem for families with children and couples who inexplicably require continuous physical contact.

The fastest (current) way: the Southwest method

Southwest Airlines uses the unassigned seat method: People get on the plane in their order of check-in, but they have no assigned seat, and can just sit down wherever they like. Sadly, there is no video for it, but it is the fastest way to board a plane that any airline currently uses.

It works because passengers spend less time waiting in line in the aisle. If there's a line in front of you or someone taking a long time to put his bag in the overhead bin, you have the freedom to just sit down in the row you're standing at currently instead of waiting to get past. In doing so, you're clearing the aisle and making things faster for the people behind you.

The downside of this method is that some people get stressed about the idea of having to choose their own seat and don't like waiting in line (or checking in online) for the chance to pick earlier. People also like to sit with friends and family, and passengers who pick their seat later on in the process might not find any blocks of open seats together.

In the Mythbusters experiment, this method led to lower customer satisfaction scores, even though it was fastest. The outside-in method, which was nearly as fast, scored much higher.

The very best (theoretical) way: the Steffen method

Jason Steffen, a physicist who got interested in plane boarding while stuck in line at the Seattle airport and subsequently conducted much of the research in this area, came up with an even better boarding system using computer models.

Steffen's method is a close relative of the outside-in method, but instead of allowing all window seat passengers to board first, it creates a choreographed sequence of them to avoid any aisle waiting at all.

Basically, window seat passengers from one whole side of the plane are sent in, followed by the window seat passengers from the other side. But the rows of passengers allowed in are staggered, so you never have multiple passengers using the same aisle space to sit down or put their bags into the overhead bins. (Example: you send in 36A, 34A, and 32A, then 35A, 33A, and 31A).

This eliminates waiting while someone in your row gets up to let you in (like the outside-in method), but also makes sure that at any given time, the passengers getting on are accessing completely different rows and overhead bins, further cutting down on congestion.

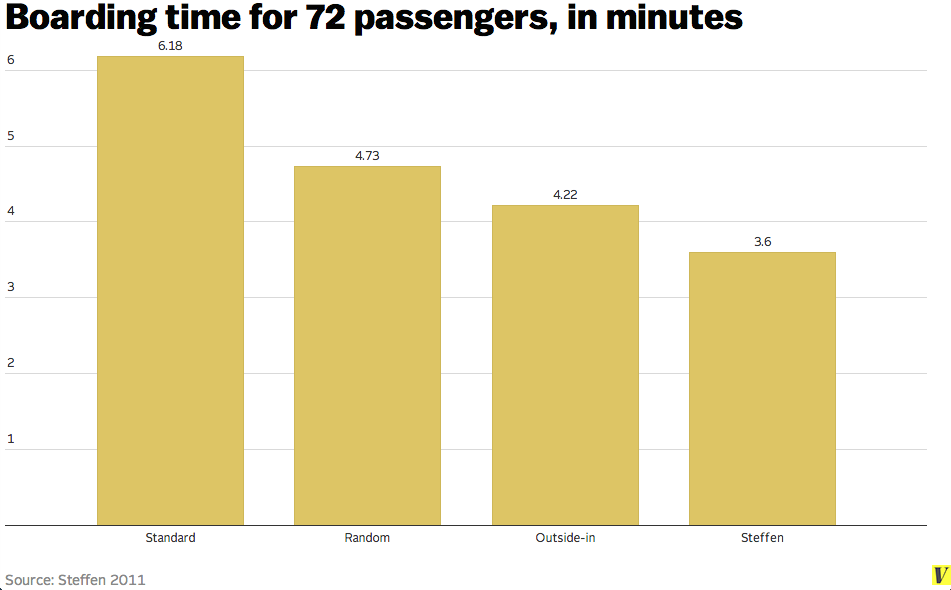

This method wasn't tested in the Mythbusters episode, but Steffen tested it himself. His experiments were simpler (they used a 72-seat plane), but they showed the Steffen method was faster than the standard, random, or outside-in methods.

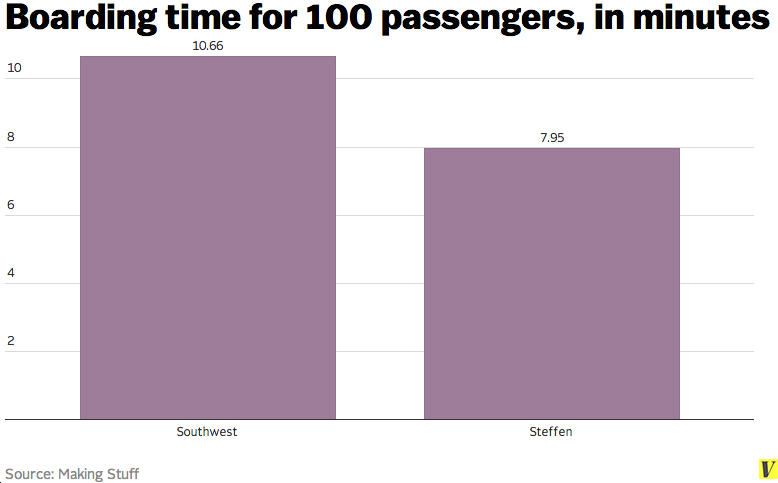

In a recent episode of the PBS series Making Stuff (about 36 minutes in), the Steffen method was directly tested against the Southwest method for 100 passengers. In a single trial, the Southwest method took 10 minutes and 40 seconds, and the Steffen method took 7 minutes and 57 seconds.

Now, it's hard to say whether the Steffen method would be feasible for real-world use; it'd require passengers to be in an absolutely precise order, and parents wouldn't be able to board with their small children if they want to sit next to them on the flight. Still, it's clear that this is the fastest method possible.

So why don't airlines use the best methods?

A great question. These methods are all unquestionably faster than the standard method, so they would speed up the turnaround times, theoretically saving airlines money. But almost none of the airlines use them.

One possible answer is that the current system actually makes them more than they'd save by switching. As Businessweek pointed out, airlines often allow some passengers to pay extra to board early and skip the general unpleasantness. If the entire boarding process was faster to begin with, many people might not pay extra to skip it.

For passengers, though, this makes no sense. Most of us are waiting in line longer than necessary, and those who pay extra are sitting on planes longer than necessary. No one is getting to their destination any faster, and everyone is paying higher base prices for tickets, because for every minute a plane is being boarded — instead of flying somewhere — an airline is turning less profit.

Correction: This article previously implied flight crews are paid for their time during the boarding process. For most airlines, they're paid starting when the plane pulls away from the jet bridge.