Andy Warhol – Birmingham Race Riot (1964)

The crime in this troubling work of art is not being perpetrated by "rioters", but by the police. As demonstrators take to the streets for civil rights in Birmingham, Alabama, a police officer deliberately sets a dog on an unarmed man. So this photographic image is evidence. Warhol, so often seen as a heartless observer of celebrity and sleaze, carefully chose it and turned it into a print to make that evidence permanent, indelible, unforgettable.

Leonardo da Vinci – A Man Being Pickpocketed (c 1493)

The world is grotesque and unkind in this disturbing drawing. Here crime is an ugly image of human coldness. A noble and lofty-looking individual – someone like da Vinci himself, perhaps, with his head in the clouds – is surrounded by monstrous, braying characters. As they mob him, one reaches behind his back to relieve him of his money. The Royal Collection, which owns this masterpiece, claims the thugs are "gypsies", but that is unnecessarily specific. More likely this is a generalised – and bleak – portrait of humanity at its best and worst.

Paul Cézanne – The Murder (1867-8)

Cézanne is famous for apples and card players, for paintings of deep silence. But the young Cézanne was a mixed-up kid. He was so close to the edge that his former school friend Émile Zola used him as the model for a doomed artist in his novel The Masterpiece. Nowhere is Cézanne's dangerous mind more visible than in this wild, savage early painting of a brutish murder. It seems a confession of dark urges, a revelation of something violent in art itself.

Weegee (Arthur Fellig) – Their First Murder (1941)

In this raw and shocking photograph of New York street life in the 1940s, the great Arthur Fellig – he got his nickname Weegee from his almost supernatural ability to get to crime scenes before the police, as if he had a weegee board to contact the newly dead – uses violent crime as an image of the loss of innocence. A crowd of kids jostle to see the horrific aftermath of a killing. We can't see who was murdered or how brutal it was. Instead, we see murder reflected, darkly, in the eyes of these children.

Michelangelo Caravaggio – The Cardsharps (c 1594)

When Caravaggio arrived in Rome in the 1590s, a young man from northern Italy with little money and no reputation, he concentrated on scenes close to the violent semi-criminal life he led. Here an innocent rich youth is being fleeced by cardsharps – a scene the artist could witness every day in the area around Rome's Piazza Navona. Another painting he created at this time, The Fortune Teller, shows a young woman deftly removing a man's ring as she pretends to read his palm. In both pictures Caravaggio is on the side of the clever crooks.

Titian Vecelli – The Miracle of the Jealous Husband (1511)

This powerfully realistic wall painting takes us aback. It is not the kind of mythological feast one expects of Titian. Instead, it is a matter-of-fact scene of cruel Renaissance life. Titian lived in Venice, where Shakespeare set his tragedy Othello, and like Othello, the husband in the painting is so obsessively jealous he is about to commit murder. As his wife begs him to relent, he stands above her with a knife, ready to strike. Man and woman are both dressed in contemporary 16th-century clothes; to Titian's original audence, this painting was like a real-life crime documentary, or a photograph by Weegee.

René Magritte – The Menaced Assassin (1927)

In this eerie surrealist painting, a murderer nonchalantly haunts the scene of his crime, unaware that it is surrounded by detectives who wait to pounce on the perpetrator. How long have they been watching? It seems that the voyeurs at the window and the bowler-hatted men, one armed with a club and another with a net, who stand concealed in the room must have been there when the woman was killed. They are complicit. Magritte's deadpan art unsettles by melting boundaries between reality and fantasy. Here he reveals that crime and punishment are mirrors of each other, that detectives and police officers are mysteriously dependent on the existence of crime.

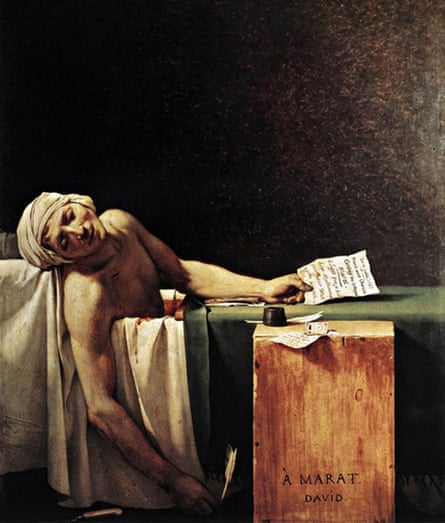

Jacques-Louis David – The Death of Marat (1793)

For David, who actively supported and participated in the most radical acts of the French Revolution, the death of one of its most eloquent enthusiasts, Marat, was an unforgivable murder. In fact, Marat was knee-deep in violence. He passionately advocated executing aristocrats and moderates to save the Revolution from supposed enemies. His assassin, Charlotte Corday, saw herself as a political criminal, a legitimate avenger. David's painting crushes such ambiguities with one of art's great images of secular martyrdom. In painting the horror of the crime scene, he turns Marat into a revolutionary saint.

WR Sickert – The Camden Town Murder Series (1908)

Contrary to some silly theories, the brilliant British modern painter Sickert was not Jack the Ripper. But he was haunted by the Camden Town murder, a killing that, for him, typified the desperate lives of Edwardian London's most vulnerable people. His paintings that meditate on this real-life crime focus on poverty and desperation, as a man and woman wonder how they will pay the rent for their dingy room. Sickert is not unhealthily morbid but socially concerned – how mean of Ripperologists to turn his compassionate art into evidence against him.

Giovanni Bellini – The Assassination of St Peter Martyr (c 1507)

This haunting picture graphically depicts a medieval murder. St Peter Martyr was an inquisitor whose job was to exterminate the Cathar heresy in southern France in the 13th century. Cathars ambushed him in a forest and killed him – thus giving the official church even more excuse to persecute "heretics". Bellini sets the scene in a spookily beautiful woodland, where violence erupts in a cinematic explosion of energy and agony. He painted this at a time when artists like Leonardo and Michelangelo were pioneering the portrayal of violent action. Yet Bellini's innate stillness and silence make the mute mayhem of this painting all the more sinister.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion