For Depression, Prescribing Exercise Before Medication

Aerobic activity has shown to be an effective treatment for many forms of depression. So why are so many people still on antidepressants?

Joel Ginsberg was a sophomore at a college in Dallas when the social anxiety he had felt throughout his life morphed into an all-consuming hopelessness. He struggled to get out of bed, and even the simplest tasks felt herculean.

“The world lost its color,” he told me. “Nothing interested me; I didn’t have any motivation. There was a lot of self-doubt.”

He thought getting some exercise might help, but it was hard to motivate himself to go to the campus gym.

“So what I did is break it down into mini-steps,” he said. “I would think about just getting to the gym, rather than going for 30 minutes. Once I was at the gym, I would say, ‘I’m just going to get on the treadmill for five minutes.’”

Eventually, he found himself reading novels for long stretches at a time while pedaling away on a stationary bike. Soon, his gym visits became daily. If he skipped one day, his mood would plummet the next.

“It was kind of like a boost,” he said, recalling how exercise helped him break out of his inertia. “It was a shift in mindset that kind of got me over the hump.”

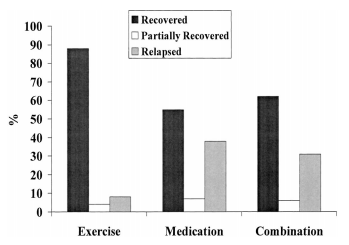

Depression is the most common mental illness—affecting a staggering 25 percent of Americans—but a growing body of research suggests that one of its best cures is cheap and ubiquitous. In 1999, a randomized controlled trial showed that depressed adults who took part in aerobic exercise improved as much as those treated with Zoloft. A 2006 meta-analysis of 11 studies bolstered those findings and recommended that physicians counsel their depressed patients to try it. A 2011 study took this conclusion even further: It looked at 127 depressed people who hadn’t experienced relief from SSRIs, a common type of antidepressant, and found that exercise led 30 percent of them into remission—a result that was as good as, or better than, drugs alone.

(Psychosomatic Medicine)

Though we don’t know exactly how any antidepressant works, we think exercise combats depression by enhancing endorphins: natural chemicals that act like morphine and other painkillers. There’s also a theory that aerobic activity boosts norepinephrine, a neurotransmitter that plays a role in mood. And like antidepressants, exercise helps the brain grow new neurons.

But this powerful, non-drug treatment hasn’t yet become a mainstream remedy. In a 2009 study, only 40 percent of patients reported being counseled to try exercise at their last physician visit.

Instead, Americans are awash in pills. The use of antidepressants has increased 400 percent between 1988 and 2008. They’re now one of the three most-prescribed categories of drugs, coming in right after painkillers and cholesterol medications.

After 15 years of research on the depression-relieving effects of exercise, why are there still so many people on pills? The answer speaks volumes about our mental-health infrastructure and physician reimbursement system, as well as about how difficult it remains to decipher the nature of depression and what patients want from their doctors.

Jogging as medicine

“I am only a doctor, not a dictator,” insists Madhukar H. Trivedi, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. “I don't tell patients what to do.”

Trivedi is one of the forefathers of the movement to combat melancholy with physical exertion. He’s authored multiple studies on the exercise-depression connection, and workouts are now one of the many weapons in his psychiatric arsenal. But whether any given treatment is right for a particular person is entirely up to that patient, he said.

“I talk about the pros and cons about all the treatment options available—exercise, therapy, and pills,” he said. “If a patient says, ‘I'm not really keen on medication and therapy, I want to use exercise,’ then if it's appropriate, they can try it. But I give them caveats about how they should be monitoring it. I don't say, ‘Go exercise and call me if it doesn't work.’”

Here’s how he goes about this unconventional type of prescription:

First, Trivedi must gently raise the idea of exercise as a treatment option—patients often don’t know to ask. (There are no televised pharmaceutical ads for running, he notes.) He then tells patients about the studies, the amount of exercise that would be required, and the heart rate they’d need to reach. Based on a recent study by Trivedi and others, he recommends three to five sessions per week. Each one should last 45 to 60 minutes, and patients should reach 50 to 85 percent of their maximum heart rates.

He and the patient then blueprint a weekly workout schedule together. Not doing enough sessions, he warns, would be like a diabetic person “using insulin only occasionally.” He encourages patients to use FitBits or other monitoring gadgets to track their progress—and to guilt them off the couch.

Trivedi says this approach rests on three key elements. “One, you have to be very clear with patients that just because exercise has been shown to be efficacious, it doesn't work for everyone. Two, the dose of the treatment is very important; you can't just go for a stroll in the park. And three, there has to be a constant vigilance about the monitoring of symptoms. If the treatment is not working, you need to do something.”

That “something” could be adding antidepressants back into the mix—but only if the workouts have truly failed.

“People will take the disease and treatment lightly,” he said, “if they know Paxil is coming.”

The insurance challenge

When it comes to non-drug remedies for depression, exercise is actually just one of several promising options. Over the past few months, research has shown that other common lifestyle adjustments, like meditating or getting more sleep, might also relieve symptoms. Therapy has been shown to work just as well as SSRIs and other medications. In fact, a major JAMA study a few years ago cast doubt on the effectiveness of antidepressants in general, finding that the drugs don't function any better than placebo pills for people with mild or moderate depression.

The half-dozen psychiatrists I interviewed said they’ve started to incorporate non-drug treatments into their plans for depressed patients. But they said they’re only able to do that because they don’t accept insurance. (One of the doctors works for a college system and only sees students.)

That’s because insurers still largely reimburse psychiatrists, like all other doctors, for each appointment—whatever that appointment may entail—rather than for curing a given patient. It takes less time to write a prescription for Zoloft than it does to tease out a patient’s options for sleeping better and breaking a sweat. Fewer moments spent mapping out jogging routes or sleep schedules means being able to squeeze in more patients for medications each day.

“[Psychiatrists] can probably do four medication-management visits in an hour,” said Chuck Ingoglia, a senior vice president at the National Council for Behavioral Health. “If they were doing therapy, they might see one person for 50 minutes.”

An insurance company might pay an internist and a psychiatrist both $100 for an appointment, but a primary care check-up might take 15 minutes while a thorough conversation with a psychiatrist takes 40 or more.

Because of these constraints, psychiatrists are among the least likely specialists to accept insurance—only about 55 percent of them do. Henry David Abraham, a psychiatrist in Lexington, Massachusetts, said he stopped accepting insurance once he realized his patient visits were becoming too rushed.

“I was seeing patients for 15 minutes each to give them drugs,” he said. “What would my mentors say about that quality of care? They would say, ‘Horrible!’”

He now sees patients on a sliding scale, with the wealthy essentially footing the bill for the poor. His sessions include a range of treatment options, including therapy.

“One patient lost a husband to cancer, and medication may take the edge off of some of those emotions, but the process she requires is to work through the elements of grief,” he said. “There's not a pill for that.”

Meanwhile, psychiatrists who take insurance are increasingly less likely to offer talk therapy—or longer appointments of any kind—because licensed social workers and psychologists can offer the same types of sessions at lower rates.

“If you're an insurance company, and you can get a social worker to do therapy for $50, that becomes the floor,” Ingoglia said.

When Brittany, a woman who lives in northern Virginia, first began experiencing panic attacks a few months ago, she turned to a series of providers in her insurance network. None of the doctors she saw wanted to discuss anything but drug options, she said.

“They were all just throwing medication at me,” she said. (She asked that I not use her last name). “I said I don’t want medicine, but they didn't want to talk about a long-term therapeutic plan.”

She went through eight different providers before finally finding a psychiatrist who helped her establish a plan to do yoga several times a week to manage her panic disorder. Those psychiatrist appointments are 90 minutes long.

Exacerbating all of this is the fact that there’s a shortage of psychiatrists, and the needs of people with mental health issues are increasingly being addressed by primary-care doctors, who now provide over a third of all mental health-care in the U.S. Sixty-two percent of all antidepressant prescriptions are now written by general practitioners, ob-gyns, and pediatricians.

But general practitioners aren’t always as equipped as psychiatrists to diagnose and treat depression. In 2007, 73 percent of patients who were prescribed an antidepressant were not given psychiatric diagnoses. In other cases, primary care doctors may balk at the idea of prescribing any interventions because they don’t feel they know enough about depression.

Writing in The New Yorker last year, primary care internist Suzanne Koven said she’s often at a loss when faced with “the lawyer who’s having trouble meeting deadlines and wants medication for attention-deficit disorder. Or the businesswoman whose therapist told her to see me about starting an antidepressant.”

She feared she lacked “the time or training to diagnose and manage many psychiatric disorders,” she wrote.

Managing life's roadblocks

Let’s say you’re a psychiatrist who has managed to start incorporating sleep, exercise, and other non-drug remedies into a patient’s depression treatment. Congratulations! You now face a patient who is, very possibly, lethargic, unsatisfied, and lying about how many times he or she went running last week.

That is, if you can convince the patient to try anything other than drugs in the first place.

Julia Samton, a psychiatrist who practices in New York City, said she prescribes medications as a “third-tier resort” after lifestyle changes and therapy have been ruled out. She spends 45 minutes on each appointment, attempting to punch through her patients’ stony Manhattanite exteriors and expose the foundations of their agony.

“There are some people who say all they want is medication,” she said. “But they are the ones who are suffering tremendously and have a difficult time accessing their mental life. They want things fixed, and fixed right now.”

She said some of her patients are lured by the drug ads they see on TV— charming little spots that make it look like a gloomy day is nothing an SSRI can’t handle.

“It's evocative to see a commercial where your world could change from black and white to color,” she said.

Beth Salcedo is a psychiatrist near Washington, D.C. People in this perpetual type-A convention of a town tend to have too much work, too-lofty aspirations, too high a rent, and too little time left before their evening networking event starts.

“I think it's difficult to convince people to spend half an hour a day on exercise when they have kids, a job, and it can take months to see the benefit,” she said.

Some patients claim they can’t make time for the gym, or are adamant that they can’t afford to sleep more than six hours each night. And lawyers who work 16-hour days are not going to sit through long counseling appointments no matter how many peer-reviewed studies you wave at them.

“What do you do? Do you let them walk around depressed?” Salcedo said. “Or do you offer them a treatment that they'll accept? Everyone has to do the thing that works for them.”

And despite its merits, exercise is not nearly as portable or painless as a tablet.

Salcedo had one patient whose mood entirely depended on her workouts. The hitch was that her exercise of choice was swimming—and the only pool she had access to was outdoors. “In the spring, fall, and winter, it wasn't so easy,” Salcedo said.

Depressed patients are also more likely than most to feel unmotivated, so even the best-laid exercise treatment plan can be thwarted by a few days of staying in bed for an extra hour.

“Depressed patients have apathy or a lack of energy. Or they have anxiety disorders so they're not going to go to the gym. Or they're afraid to be seen jogging across Monument Avenue,” said Joan Plotkin Han, a staff psychiatrist at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond. Still, she pushes it with her more intrepid patients. “I don't want to be that intimidating or threatening, but I'm a nag. And I will nag them.”

Of course, sometimes exercise works as a multiplier, augmenting the effectiveness of an existing treatment, including drugs or therapy, or simply by helping the patient regain agency in their lives. Many patients recover from depression faster when the disease is attacked through multiple approaches simultaneously.

Ginsberg said exercise didn’t cure him, but it did give him the energy to sort through the origins of his inner turmoil. And Brittany did eventually go on SSRIs to halt her nightly panic attacks—but now that yoga has her anxiety under control, she’s tapering off the drugs once again.

Exercise, like any other treatment, won’t work for every depressed patient. But the psychiatrists who incorporate it into their practices are finding that the only way it can work is if it’s treated like real medicine.

“The issue is that exercise seems as straightforward and simple as apple pie and your mom,” Trivedi said. “Everybody knows what it is, so it's misunderstood. It’s important to explain to patients the seriousness of the disease they have and the nuances of the intervention they need.”