During a busy lunch rush at a typical Chipotle restaurant, there are 20 steaks on the grill, and workers preparing massive batches of guacamole and seamlessly swapping out pans of ingredients. Compared to most fast-food chains, Chipotle favors human skill over rules, robots, and timers. Every employee can work in the kitchen and is expected to adjust the guacamole recipe if a crate of jalapeños is particularly hot.

So how did the Mexican-style food chain come to be like this while expanding massively since the 2000s?

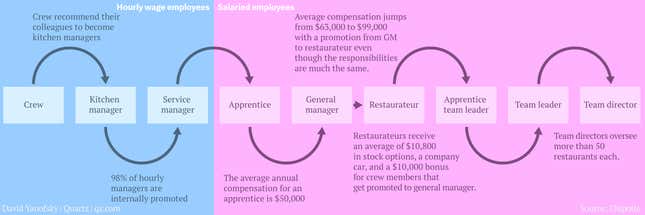

In 2005, the US company underwent a transformation that would make its culture as distinct as its food. As more than 1,000 stores opened across the US, the company focused on creating a system where promoting managers from within would create a feedback loop of better, more motivated employees. That year, about 20% of the company’s managers had been promoted from within. Last year, nearly 86% of salaried managers and 96% of hourly managers were the result of internal promotions.

Fundamental to this transformation is something Chipotle calls the restaurateur program, which allows hourly crew members to become managers earning well over $100,000 a year. Restaurateurs are chosen from the ranks of general managers for their skill at managing their restaurant and, especially, their staff. When selected, they get a one-time bonus and stock options. And after that they receive an extra $10,000 each time they train a crew member to become a general manager.

Co-CEO Monty Moran described the program to Quartz as a way to create “gravity” at the managerial level—to make sure that great managers are given the chance to make individual stores great. They stay involved training excellent people instead of leaving to become less effective middle management at the corporate level.

“The foundation of our people culture, on which everything else stands, is the concept is that each person at Chipotle will be rewarded based on their ability to make the people around them better,” Moran told Quartz.

The origins of the restaurateur

One of Chipotle’s first restaurateur was Sahul Flores. Eleven years ago, Flores was 22 and a part-time crew member in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Today, he runs more than 60 restaurants as a team director. He spends his days going store to store, talking to each crew, and helping to identify future managers.

But it was a lucky accident that brought him to Chipotle in the first place.

In 2002, Flores worked in a restaurant in Houston, Texas with no plans to leave. But after his sister tracked down their father, whom the pair had never met, Flores agreed to join her on a trip to Milwaukee to meet him. After deciding to spend the summer there, Flores wandered into a Chipotle restaurant looking for a job. It happened to be a training day, and the restaurant wasn’t open yet. He wound up chatting with the manager and eventually was hired part-time to prepare the tortillas for burrito making.

Two-and-a-half months later, Flores was promoted to kitchen manager and two months after that, apprentice manager. It took him two more months to become acting manager, and another three to be a full manager. In just over nine months he’d risen through the ranks, much more quickly than workers typically do in the industry.

“In about a year I went from crew to general manager, from making $7 bucks an hour to a good salary with benefits and everything,” Flores said. “It’s funny because you would think, in a year I got promoted, all these great things happened, how could you top that? That was barely even the beginning. It was just a step.”

In the fall of 2005, a group of Chipotle executives walked into the Milwaukee location where Flores worked. One of the men was Chipotle’s founder, Steve Ells. Another was Moran, who was then COO and is a high school friend of Ells. Moran and Ells were traveling across the country for investor meetings ahead of the company’s impending IPO. At each store visit they talked to managers and crew members, the beginning of a process that would change Flores’s life as well as the Chipotle’s trajectory.

Moran had been the company’s outside lawyer. His transition to working full-time as the company’s COO in 2005 was part of a huge cultural transition, which helped enable a big business one, too. The company was going public. Longtime partner McDonalds was no longer an investor, and Chipotle had never franchised. It had to manage and fund its own growth. It needed a culture that was scalable and could produce a multitude of excellent managers.

Flores recalls Ells saying to him: “Do you know that you run your restaurant as good or better than I did the stores in Denver?”

After talking to the crew and inspecting the restaurant, Moran asked Flores how he liked it at Chipotle, and wondered who was teaching him to succeed.

Flores told him the company didn’t teach him—he learned on his own, mostly from his crew. He liked working there, but was frustrated by the fact that the manager at a nearby branch was rewarded despite his store’s poor performance.

“The problem was we weren’t picking the best people,” Moran said. “Why? Well, the best people don’t come from fast food that often to be honest and if they do they’re usually employed. They’re not looking [for a job] if they’re good. We were taking bad people and putting them over managers [who were] good people.”

When Moran asked about the company’s hiring policy, Flores told him that he could train all nine of his crew members to be better managers than the culinary school graduates he had been training for the company.

Moran said he agreed 100% and told him things were going to change.

“Since then, he’s kept that promise,” Flores says.

The most important person at the company

Around the time of the 2005 visit to Milwaukee, Moran had recently finished going through eight weeks of manager training and was speaking to other managers around the country.

“The first thing I learned was that the manager is absolutely the most important person at the company at Chipotle,” Moran said. “When I looked at how we trained and rewarded our managers, we didn’t treat them that way.”

Today, Moran is co-CEO and in charge of employee culture and the restaurateur program.

Ells had been asking Moran to join the executive team for years but held off until 2005 because he had no background in food. For years he’d worked as general counsel for Chipotle, during which time he was partner (and eventually CEO) of the rapidly growing Denver law firm Messner Reeves. There, he’d built an excellent culture, which is why Ells wanted him.

“Monty, you may be a great lawyer but that’s not what you’re best at,” Moran recalls Ells telling him. “What you’re best at is being a leader. That’s more important. You should come to Chipotle and use that for a company of 10,000 instead of firm of 600.”

At Messner Reeves, Moran had cultivated a concept that would come to define Chipotle as well: hiring, rewarding, and empowering top performers.

The common element among the best-performing stores was a manager who had risen up from crew. So Moran started to outline a program that would retain and train the best managers, and reward them to the point where they would be thrilled to stay on.

After Flores expressed his frustration, Moran showed him his early notes for the restaurateur program, which is unique among fast food restaurants in that it ties pay and promotion to how well you mentor people, rather than store sales.

“It was a great meeting but I didn’t know what was going to happen. At most companies you meet the top execs and then you never hear from them again,” Flores says.

A few weeks after the October meeting, while vacationing in Houston, Flores got a call on his cell from Ells and Moran letting him know that he had been promoted to restaurateur and was getting a $3,000 bonus. Rather than waiting until he returned to Milwaukee to get him the check, it was delivered to him in Houston the following day. At the time his salary was around $38,000, and the bonus was meaningful.

“That’s when I knew the company was special,” Flores said.

After the promotion and rollout of the restaurateur program, Moran would call Flores every three months to make sure things were continuing to improve.

Moran remains the ultimate arbiter of promotions to restaurateur, which helps keep the title elite. He spends a significant amount of time on the road and personally interviews every candidate. The difference between an average restaurant and one run by a restaurateur is palpable, Moran says.

“I walk into a Chipotle and the first thing I do is take notes on how I feel,” Moran says. “Is it fun, is it upbeat, is there camaraderie, is there pride? Enthusiasm? Is the place clean, does it sound and smell good? Is the line moving fast? Do the customers seem happy? How does it feel? And if it doesn’t feel excellent then I know it’s probably not going to become a restaurateur restaurant.”

The goal of every manager is to become a restaurateur, so the ones that aren’t quite there get feedback on how they can improve and eventually make it.

There are more than 400 restaurateur overseeing about 40% of the company’s stores. The goal, in time, is for every restaurant to have a manager at that level. After the promotion, a restaurateur continues to manage her store and some of the best ones advise other stores as well, a move that comes with another pay bump.

A path to success

Since its IPO in 2006, Chipotle’s growth has been exceptional. Sales have increased from $826 million that year to $3.2 billion last year. And the company had 9.3% growth in comparable store sales last quarter, which is remarkable for a 21-year-old company that hasn’t raised prices recently.

Moran attributes the company’s continued strong performance in part to its culture. In the company’s most recent earnings call, Moran tied the two explicitly, and analysts have cited it as a driver of Chipotle’s rapid growth.

Beyond the restaurateur program, Chipotle emphasizes raising employees through the ranks. The crew itself submits candidates to be considered for kitchen manager, the first step on a well-defined path to management. The restaurateur job is the end goal, but it starts with trying to find real potential in every hire.

“We don’t care about experience very much,” Moran says. “In fact, I think experience at another fast food restaurant is as likely to be a negative as it is to be a positive. We look for people who possess certain qualities that you can’t teach. You can teach somebody experience, how to hold a knife and prep ingredients, or even to run a restaurant.”

On that front, Moran echoes Google hiring head Lazslo Bock who said he discounts expertise when hiring for functions like human resources and finance. A less experienced person is more likely to mess up, Moran acknowledges. But when you hire bright people, they catch on quickly and come up with better solutions.

Moran has come up with a formal list, first conceptualized at his law firm, of 13 characteristics that every Chipotle hire should possess. It’s now a checklist given to hiring managers, and says Chipotle employees should be:

- conscientious

- respectful

- hospitable

- high energy

- infectiously enthusiastic

- happy

- presentable

- smart

- polite

- motivated

- ambitious

- curious

- honest

The idea was to come up with a list of traits you can pick up on in a relatively short meeting. Inexperienced managers tend to look for the person who can help right away rather than indicators of long term success, Moran says.

Moran believes so much in this method that he tests it during Chipotle’s all-manager meetings in Las Vegas, interviewing a series of candidates for a few minutes on stage in front of 2,000 people. There is 80-90% agreement, he says, on which candidates possess those characteristics.

The biggest threat to Chipotle is that it won’t be able to maintain consistency and quality as it continues to scale up. As of the end of last year, it had about 45,340 employees, including roughly 3,740 salaried employees and about 41,600 paid hourly wages. As of the most recent fiscal quarter, there are 1,595 restaurants and nearly 200 opened last year. The company plans to open between 180 and 195 restaurants this year.

Chipotle’s increasing size and insistence on cooking almost everything on location present a unique challenge. That growth rate puts strain on culture, and if growth slows, it could put strain on the company’s cost structure. There are higher salaries—salaries at the manager level are high and the company offers substantial benefits, but wages for crew and hourly managers are fairly close to the industry average for fast food. And ingredients are expensive. While the company has managed to keep costs relatively low even as it expands, there’s not much it can do about food prices, and there could be limits to efficiency.

But Moran is confident that the culture is self-reinforcing and it’s his mission to make sure the company maintains it. The restaurateur program will be in place at the company’s new Shophouse chain, a Southeast Asian themed fast-casual restaurant similar to Chipotle.

“When you have something people are getting because of seniority, you get rid of it,” Moran says. “When you see that the best managers make only a tiny bit more than the worst, you say ‘we’re not going to do that anymore.’ I’m proud of of this culture because it would work anywhere in the world.”