The Facebook Effect on the News

Social networks are the new front page and homepage for news. But on Facebook, it's not the "news" that readers come to see or click to leave.

Around this time last year, I considered writing a story claiming that Facebook and Twitter were the new "homepages" for news on the Internet. It was going to be about how, if the Web had ripped out the article pages of newspapers and magazines and scattered them to the wind, Facebook and Twitter had pinched them from the air and stacked them in easy, vertical columns that were becoming our new first-look sources for the day's events.

A year ago, social networks are the new homepage seemed like an (almost) original observation. Today, it's just a boring fact.

That Facebook is a prodigious firehose is clear. The question is: What sort of stories get the water?

The Atlantic's experience is indicative, but limited: A few months ago, I was talking with a colleague about how our most successful stories on Facebook often aren't news-pegged—that is, they're not about recent or upcoming events. Instead, they are what journalists call "evergreen" stories—essays about diets, Millennials, and happiness, studies on coffee and decision-making, or beautiful photos. This was around the time that Upworthy—notable purveyor of sugary-sweet videos and "you won't believe what happens next" headlines—was riding Facebook's rocket ship, not as a "news" organization, but as a savvy scavenger and marketeer.

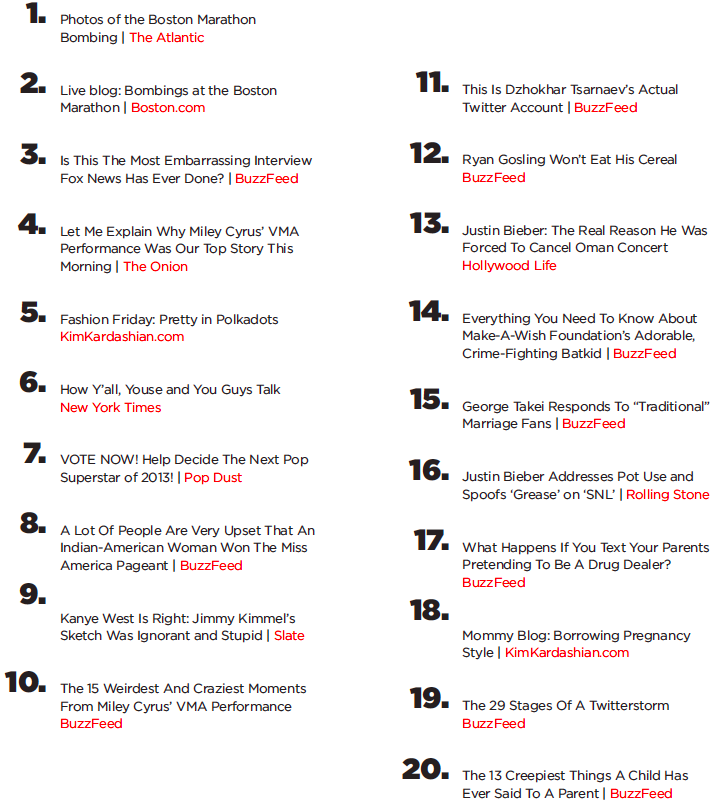

To see this more clearly, let's compare the BuzzFeed network's most viral stories—i.e.: the stories that go biggest on Facebook—to the top stories on Twitter and the most-searched stories. First, here are the top stories on Twitter in 2013. It's a blend of news, like terrorist attacks and music shows, and evergreen silliness with Ryan Gosling and Kim Kardashian.

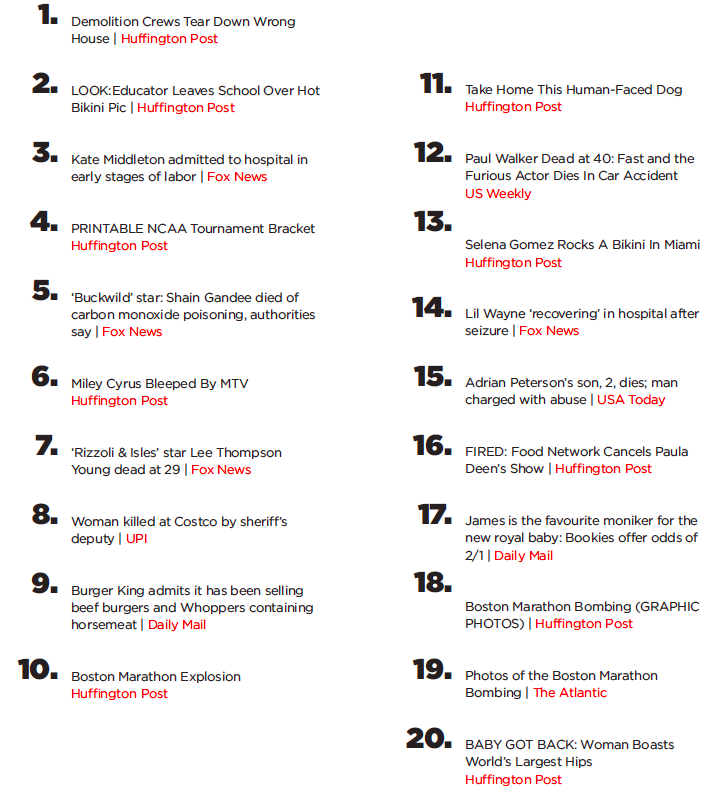

Now here are the stories with the most search traffic in 2013. Just about all of them arguably count as "news." They describe recent events, whether it's a bikini sighting, terrorist explosion, or celebrity death. Even "Take Home This Human-Faced Dog" at #11 turns out to be about an newly up-for-adoption dog (with an undeniably human face).

Twitter is for news—ish. Search is for news—full stop. But Facebook?

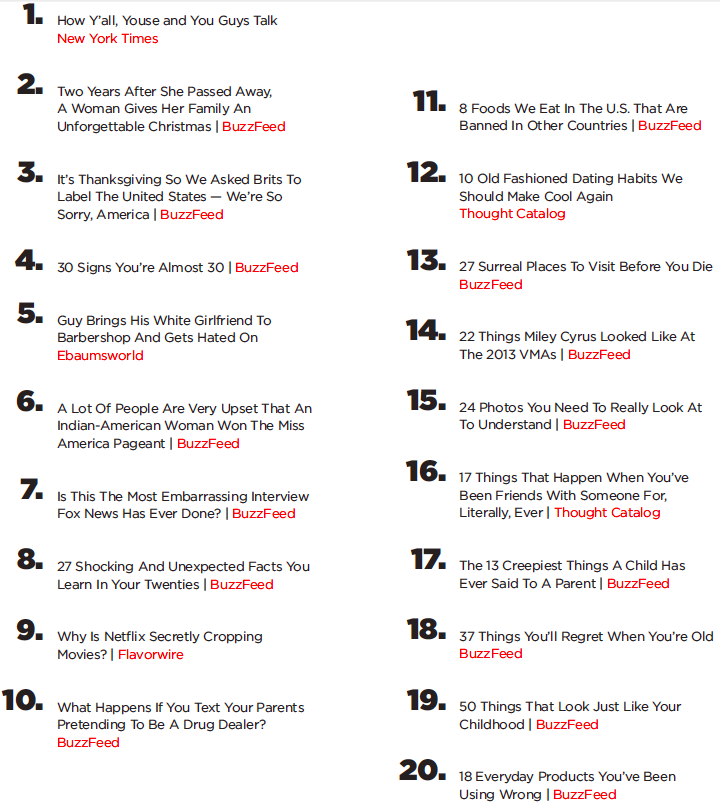

Of the 20 most viral stories on BuzzFeed's network, only seven deal with recent events. Only three deal with what you might call national news stories: the Miss America Pageant, Netflix technology, and the Video Music Awards (not quite A1 fare, but news, nonetheless). But the vast majority of these stories aren't really news, at all. They're quizzes about your accent, lists of foods and photographs, funny reminders of what life feels like as you age. For lack of a better term: They're entertainment.

If this feels like the wind-up before the Facebook-Has-Destroyed-the-News finale, you can relax. Entertainment was beating up on news long before Zuckerberg was born. People always outsold Time. Broadcast sitcom ratings always made mincemeat of PBS. The back sections of the newspaper have long cross-subsidized the foreign coverage of the A-section.

A key difference between the old forms of news and entertainment and Facebook is that the News Feed is entirely our creation, even if it reveals itself as an idiosyncratic and surprising list of stories. After all, Facebook doesn't "make" the News Feed. The friends and pages we follow contribute every story, and Facebook organizes them with a machine-learning algorithm that studies our past behavior to predict what stories should appear at the top. Since you choose your friends and you choose your interactions with your friends' posts, it's hardly a stretch to say that you choose your own News Feed.

You can make your News Feed a news feed if you really want to. You can hide your most frivolous friends, follow the Facebook page of every national newspaper, and share every NBC News link that comes your way. But you don't.

Independent studies of virality conducted out of Wharton, the National Science Foundation, and the University of South Australia have all reached the same conclusion. The stories and videos most likely to be shared, emailed, and posted on Facebook aren't necessarily the newest stories, but they are the most evocative. The most famous of these studies, by University of Pennsylvania professors Jonah Berger and Katherine Milkman, concluded that online stories producing "high-arousal emotions" were more viral, whether those emotions were positive (e.g.: happiness and awe) or negative (e.g.: anger or anxiety).

The News Feed is perhaps the world's most sophisticated mirror of its readers' preferences—and it's fairly clear that news isn't one of them. We simply prefer stories that fulfill the very purpose of Facebook's machine-learning algorithm, to show us a reflection of the person we'd like to be, to make us feel, to make us smile, and, most simply, to remind us of ourselves.