San Francisco is a great American city. And Google is a great American company. But the two are having some trouble getting along. Last week, anti-eviction protestors surrounded one of Google’s private shuttle buses, which transport employees from their urban homes to the company’s suburban campus, and staged a phony incident in which an alleged Googler unleashed his contempt for the city’s lower orders. Then, just in time for the backlash to the anti-Google backlash, prominent local startup CEO Greg Gopman delivered the real deal in the form of a Facebook rant decrying the San Francisco poor as, in essence, uppity. In other cities, Gopman wrote, “the lower part of society keep to themselves” and “realize it’s a privilege to be in the civilized part of town and view themselves as guests.”

With tensions running high, perhaps a breakup is in order.

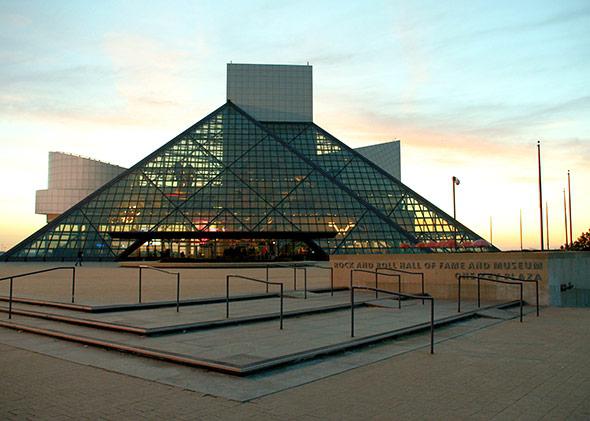

The Bay Area is sick and tired of the antics of entitled techies, and the nouveaux riches want a place where they’ll be appreciated. It’s time for federal authorities to step in and move the show someplace else. Cleveland, say.

After all, every big city has its share of obnoxious protesters and obnoxious overclassers. What makes the tensions in the Bay Area especially extreme is the fearsome competition over scarce resources—specifically housing and office space.

The influx of money, young people, and business investment into Silicon Valley hasn’t led to a construction boom and the urbanization of the area. Instead, the local towns continue to insist on strict, suburban-style zoning that essentially rules out new housing supply. Nor are city officials in San Francisco interested in rezoning to allow for more population in a city that’s currently only about half as dense as Brooklyn. The mass transit system, likewise, strains to cope with current demands (a situation not helped by the cultural gaps between the tech set and other transit stakeholders). Local officials are unable or unwilling to reform Caltrain in a way that would make it useful regional transit, and again, Valley officials won’t zone for the creation of giant office towers in downtown Mountain View and Palo Alto that would make more transit-oriented development workable.

So instead of the tech boom leading to broadly based prosperity, it leads to private buses and skyrocketing house prices. If I called the shots, I would change these policies. But if that’s not going to happen, a divorce is the second-best solution.

The problem is that it’s not going to happen on its own. Large tech companies like to be where the highest concentration of skilled tech workers is. Entrepreneurs want to be where the venture capitalists are. Venture capitalists want to be near both the skilled workers who can staff new firms and the established firms who may buy the companies. People with skills want to go where the venture capital and the employers are. Individual people or small firms can and do leave, in search of cheaper houses or other amenities, but in doing so they give up substantial benefits of agglomeration. And when they do leave, they tend to scatter—some to Austin, some to New York, a few to the Boston area, Zappos is even in Las Vegas—rather than building a new hub.

What’s needed is for a critical mass—say Google and Apple and Facebook and Twitter—to move all at once, to the same place, thus immediately creating a new tech hub. With the startups and VC firms left behind, Silicon Valley and San Francisco will still be a vibrant industry hub. But the departure of thousands of highly compensated employees of four tech giants will provide a great deal of relief to the local real estate market.

Meanwhile, our New Tech Metropolis will have enough local engineering talent and acquisition money that it will inevitably develop a startup scene of its own.

The only question is where? All you need is a city that has bigger problems than douche-y Facebook posts, creating plenty of room for local housing investment to become a win-win rather than an engine of displacement. Cities such as Buffalo, N.Y., or Pittsburgh come to mind, although unlike Detroit and Cleveland, they lack a major airport. Plans to save Detroit, however, are a bit cliché at this point, and I worry that any tech hub you tried to build there would naturally drift over to Ann Arbor, Mich., anyway. But Cleveland’s got plenty of affordable housing, plenty of available office space, flights to every important North American city, and even its own Federal Reserve bank.

The relocation of big tech companies to the North Coast would immediately create new business and employment opportunities in terms of high-end dining, fancy coffee, and other Bay Area amenities but without crowding out existing local businesses. Cleveland’s local tech companies would stand a better chance of getting investment, and over time, some employees of the big four relocators would leave and launch their own startups or VC firms. The Bay Area economy, meanwhile, will cool down considerably without negatively impacting real living standards for most people, since much of the lost activity will simply translate into cheaper real estate prices. Firms left behind will even find it easier to expand.

Obviously, this would be much more laborious than simply building more Silicon Valley where it already exists. But if the politics of increased density are too difficult, relocation really is the next best thing. The Greenhouse Tavern is delicious, LeBron might be coming back to the Cavaliers, and there’s even a casino conveniently located right downtown. Throw in a few technology giants, and it could be the next great American city. Get excited, Googlers—you’re gonna love it.