My mate Rob is a conservationist. Two years ago, he called me from Peru with a proposition. "Do you want to buy some Amazonian rainforest?" he asked. He explained that the head of Manú National Park, an area of the Peruvian Amazon, was desperate to save a strategic piece of land: 100 acres or so of rainforest that lay at the end of a road, which had become an easy, ungovernable entrance where illegal loggers could access the park and cut down trees. They planned to build a guard station on the land to protect it. The idea was simple: buy the land and stop the logging.

A few months after I'd bought the land, for the not inconsiderable sum of £6,000, I decided to visit it. The journey was long – four flights from home followed by an eight-hour drive from the city of Cusco – and dangerous, crossing the Andes, the cloud forest and the tropical lowlands on some of the worst roads in the world. And almost as soon as I arrived, I realised I'd bought a turkey. The forest wasn't the green idyll I had hoped for. There were no jaguars, no men with bones through their noses, no sodden epiphytes dripping on to poison-dart frogs. There was, to be fair, a stunningly clear stream visited by darting kingfishers, but little else to lift my spirits. Apart from the path that the loggers had hacked out, it was an impenetrable tangle of dense scrub.

It was on my first exploration that I realised I had, unwittingly, bought an illegal cocaine plantation. Cocaine thrives on the slopes of the Andes, above the lowlands, below the cloud forest. This wasn't a large crop, maybe 3,000 plants in a cleared area of forest a short hack from the path, but as soon as I saw it I was terrified; I felt like I'd stumbled into an on-going crime scene. As the landowner I was responsible; however, it was being used by someone who I doubted would take kindly to me destroying it. My understanding of the coca trade was "steer clear or die".

My patch of forest was, I discovered, considered remote and lawless. From the local people I heard tales of kidnap and robbery, the worst involving the infamous "Gringo", a local drug runner with a very nasty reputation. His father, Tito, was the previous owner of my land, and had apparently been jailed for growing and processing coca. "You have bought the most dangerous piece of land, off the most dangerous family, in the most dangerous area of southern Peru," I was told.

The National Park team, who had run out of money before they could build the guard station they had promised, were unable to help. Rob and I asked the local park guards who owned the coca plants; they directed us to a few small wooden huts on the outskirts of town. Deciding diplomacy was the only way to solve the problem, we knocked on doors until we were introduced to three men in their 30s who told us they were relatives of the coca's owners. They were nice guys, smiley and friendly in the way that narco traffickers apparently are before they kill you. We stood together in the hot, dusty street chatting: I puffed out my chest a little, as did Rob. It was, of course, bluff. I was seriously nervous. But the men agreed to harvest the coca and remove it from my land, and we arranged to meet a few days later in the coca field.

On the day of the harvest, Rob and I arrived clutching our machetes, and waited. We tried to take our minds off the armed drugs traffickers we were expecting by discussing the geography of the place; Rob pointed south to a vast, unexplored hillside where the forest lay unbroken for hundreds of miles – home to uncontacted tribes and a legendary lost city. Then we heard voices. The bark of a dog. My heart pounded. A small, yappy Chihuahua appeared in the coca field, followed closely by several women and kids. This was the harvesting crew? I laughed with relief.

I got my lesson in how to pick the leaves off the coca plants from a five-year-old girl, who stripped the plants with the speed of a factory worker. "Not too dark, not too yellow," she told me (I discovered later that the bright-green leaves are prized for containing the highest alkaloid content). There were no Colombians with medallions, no Uzis and no headless corpses. The female pickers were amazed when we told them the cost of their harvest back home. They'd never tried it in its processed form – it's not readily available in the area – but we chewed the leaves as we worked. It was like a weird summer picnic, with drugs.

Illegal is a loose term in the Amazon's "wild west". Small one-horse towns in this coca-growing belt quietly service the industry, relying on the tangle of the geography and Peru's inherent disorganisation to succeed. The towns are desperately poor and receive little from the government in the way of employment or infrastructure. So the people turn to the forest, an unimaginably vast resource.

Hence the illegal logging camp on my land. From what I could gather from the National Park guards, it belonged to a guy called Elias – a slippery, serial law-breaker and a life-long logger, not to mention the brother of the infamous Gringo. A few times I stopped in the street where he lived, meaning to confront him, but Elias was always out "working on paths", as his wife Innes described it. So I decided to literally track him down, the same way I would track an animal: from muddy footprints, to wet footprints, reading any clue I could in the undergrowth.

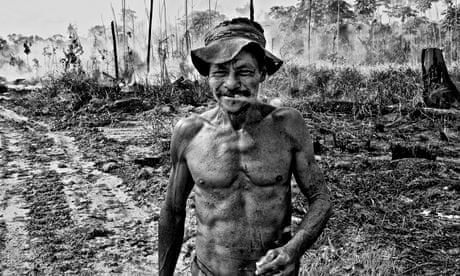

Hours later, when I finally heard his chainsaw, the thrill of the chase turned to fear. The idea of door-stepping a man engaged in illicit activity in the middle of nowhere suddenly seemed very foolish, but I continued to hack through the forest until I found him, chopping a freshly cut tree into planks. Elias was slight yet sinewy, with fingers like sausages. He was with his father, Tito; Elias explained he had grown up on the land, and Tito still referred to it as his own. They told me that they weren't really loggers, just doing the job to survive: Elias said that felling the odd tree was all he could do to clothe and feed his severely disabled daughter. I didn't believe him. I could see through his sob stories, exaggerating his predicament, and I was amused by how Elias and Tito were trying to play me – I wasn't stupid.

I felt pretty stupid the next day, when I went to Elias's house, a small shack surrounded by filthy water and sewage, and met his daughter. Heydi had fallen in a rice-threshing machine as a baby and suffered permanent brain damage. At five, she had limited motor skills and was unable to speak; her mother Innes was mocked by other women, who told her she must have drunk too much when she was pregnant.

After my first meeting with Elias, I travelled around, exploring the area for a film documentary I was making; I wanted get to know the Amazon as it really is, not the place of our romanticised imaginations. For a couple of weeks, I worked in a gold mine down river from my land, near the town of Colorado. Gold miners, like illegal loggers, have the reputation for being nasty, and Colorado is considered a dangerous place filled with drugs and the worst forms of sexual human trafficking.

The work was the toughest I have ever experienced, back breaking and dangerous. The mine owner, Erasmus, needed seven grammes of gold per day from his claim to break even and he was only ever pulling in 6.5g: the result was no one was getting paid. In the evenings the men's bodies were covered in toxic mercury deposits, left by the process of mining and washing the gold; they burned them off with a blow torch. One day I found Erasmus crying at the table in his camp. His wife Anna had miscarried in the night; miscarriage is one of the known side effects of mercury poisoning, and it wasn't Anna's first.

At every turn I met people whose lives were as difficult and tragic as those of Elias and Erasmus. These were the "bastards" I'd always blamed for destroying the Amazon. But they all seemed to have a respect for the forest, some a love for it. And all said the same thing: "Pay us, and we won't do it."

So I make an offer to Elias and Innes: I will pay Elias to replant the forest instead of logging it. We are huddled in the darkness of their wooden shack, sheltering from the rain that batters the tin roof. I expect an excited response to the idea of full-time work but, instead, Innes quizzes the hell out of me. She talks about the strained ties they have with Elias's family – relatives who would not like the idea of Elias turning good. To her, it's vital that Elias can still grow food on my land: money is all very well, but it's far less important than crops. Without time or space to grow those, she isn't interested in the idea of the job. I struggle at first to understand, but Innes has little faith in people – they have let her down all her life, and she imagines I will do the same at some point. So their crops are their only fallback. Eventually, with some compromises on both sides, they accept the offer.

Several months later things are going well – Elias is working hard and enjoying the labour. A local NGO has taken Elias on, with the support of the salary I pay him, and appointed a manager to teach him how to replant a rainforest and grow food crops harmoniously with the rainforest. I hear Elias is becoming a bit of a legend in the area. I'm pleased; he's a good guy.

I Bought a Rainforest will be on BBC2 this spring. For more information, go to digitalrainforest.co.uk

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion