How Spring Opens the Mind

People who spend more time outside in the springtime feel better, smarter, and more open-minded. Those who spend the time indoors, though, experience the opposite effect.

This time of year brings out humanity’s loosey-goosey side. For Easter, Czech people douse each other in cold water as part of an ancient fertility ritual. South Asians pelt each other with colored powered as a celebration of the triumph of good over evil. Washingtonians gawk at pink trees and listen to jazz while sitting on the grass in their pinstripes.

This kind of thing can be cathartic after a winter's worth of suffering, but there's evidence that it might be good for you, too.

We’ve long known that cold weather can dampen spirits. Depression that returns during the winter months each year—seasonal affective disorder—goes by the extremely apt acronym “SAD.”

Warm weather doesn’t really have the opposite effect, though. A number of studies, including one based on 20,818 observations in Dallas, Texas, found that there was no significant correlation between mood and temperature.

But there is evidence that winter creates a pent-up demand for nice days, so that when they finally arrive, at least at first, they make us feel measurably better. There’s something about seeing sun for the first time after months of "wintry mix" that revs up mood and makes us more mentally sharp and open-minded. In the wise words of Robin Williams, spring is nature’s way of saying “let’s party”—to the brain, as well as to the Neighborhood Aloha Barbeque Organizing Committee.

For a study published in 2005 by Psychological Science, researchers put volunteers recruited through newspaper ads through a series of tests to gauge how the weather and the amount of time they spent outside affected their mood, their memory, and how receptive they were to new information.

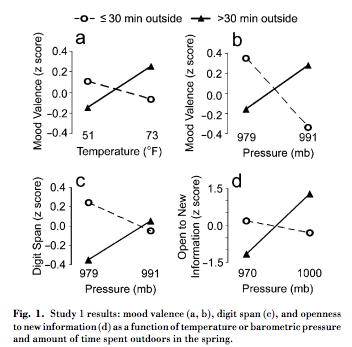

In the first test, researchers measured the temperature and barometric pressure (high pressure is typically associated with clear, sunny weather) on several days when 97 people reported their mood and how much time they spent outside. Then, the participants were asked to remember a series of numbers. They were also given a short, favorable description of a fake employee, and then given additional, unfavorable information about that same person, and then asked to assess the employee’s competence and performance. The more open-minded among them, the researchers thought, would be able to update their initial impressions with the new information before passing judgment.

All three metrics hinged on the weather and how much time the participants had spent outside. On days with high pressure—the clear, sunny ones—people who spent more than 30 minutes outside saw an increase in memory, mood, and flexible thinking styles. Those who spent the time indoors, though, saw a decrease.

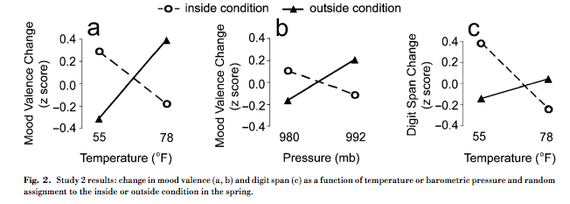

In a second experiment, the researchers asked 121 subjects to either spend time inside or outside on a warm, clear day. “Among participants who spent more than 30 minutes outside,” they reported, “higher temperature and pressure were associated with higher moods, but among those who spent 30 minutes or less outside, this relationship was reversed.”

The final study aimed to determine whether the first two tests were tainted by the fact that they took place in the spring in a northern climate, when perhaps subjects were preternaturally happy to not be wearing parkas for once. For the third study, the researchers collected data through a website from 387 respondents who lived in various climates, and they correlated the submissions with the weather in each city for that day. They found that the participants who spent more time outside during the spring, but not during other seasons, had better moods.

“Temperature changes toward cooler weather in the fall did not predict higher mood,” they wrote. “Rather, there appears to be something uniquely uplifting about warm days in the spring.”

For what it’s worth, “peak mood” occurred at 67.4 degrees Fahrenheit, lending credence to the idea, to quote Miss Congeniality, that “April 25 is the perfect date, because it’s not too cold and not too hot. All you need is a light jacket.”

In summary, across the studies, spending more time outside on clear, sunny days, particularly in the spring, was found to increase mood, memory, and openness to new ideas. People who spent their time indoors, though, had the opposite effect, and “one possible explanation for this result is that people consciously resent being cooped up indoors when the weather is pleasant in the spring.”

People in industrialized nations spend 93 percent of their time inside, but the authors suggest that “if you wish to reap the psychological benefits of good springtime weather, go outside.”

This might be a sign that in the coming weeks, you should print out this article, lay it on your cubicle desk with a Post-it note that says “OUT,” and get lost. Toss water at a Czech girl, fling colored chalk at your colleague, or at the very least go frolic through the parking lot. Tell your boss it's brain training.