Yves Behar is taking questions.

Behar, the renowned industrial designer, is standing in a glass-enclosed conference room at Art Basel, the Swiss art fair, as part of a business trip to Europe. He began in France at Cannes Lion, the annual festival for advertisers, and will finish in London, where he’ll debut his new line of furniture for Herman Miller. Today Behar is speaking on a panel with the kitchen-sink title of “New Technologies, Human Experiences, and Ethics: Discussing Design’s Future.” As it begins, he settles into his chair and faces the audience.

About 50 people of all ages crowd into the room to hear Behar discuss his work with the aid of slides. “The secret,” he says, “is in the relationship between the person and the object.”

Since moving to California in 1990, Behar has become one of the leading industrial designers of his generation, creating iconic objects for Jawbone, Herman Miller, General Electric, and Puma, among many others. The objects often have a socially progressive bent: light fixtures that promote energy conservation, say, or cheap but durable laptops that offer poor children improved access to education. Behar’s designs tend to be practical rather than flashy, and they have a history of predicting — or dictating — mass-market trends. His design for the Jambox, first released in 2010, launched a multibillion-dollar wireless-speaker market.

"The secret is in the relationship between the person and the object."

Lanky and handsome at 47, Behar keeps fit with a regimen of surfing and yoga. In a crowd he is most easily spotted by his wild tangle of brown hair, now graying at the edges, which adds a dash of mad scientist to an otherwise manicured appearance. His style is Silicon Valley dressed for a date: a fitted chambray shirt over dark denim, cuffed at the bottom. On his left wrist he wears a neon orange Up band, which he designed, and complements it with a colorful pair of surf-shop woven bracelets.

Industrial design is a curious profession. Its practitioners are not quite artists, though they are artistic; they are not inventors, though they are inventive; and they are not engineers, though the best of them bring a deep technical understanding to their work. Working freelance or in-house, industrial designers marry art and science to improve the look, feel, and function of lamps, chairs, razors and even corporate logos — anything meant to serve a practical function. Good industrial design makes a thing look good, and great industrial design builds a relationship between an object and its owner. You use it again and again. You fall in love.

Weeks after he returns from Europe, the value of Behar’s work will become clear when he sells 75 percent of his industrial design firm, Fuseproject, to a six-year-old Chinese conglomerate named BlueFocus. BlueFocus paid a reported $46.7 million for its stake, and plans to expand Behar’s model of "venture design" — forming long-term partnerships with startups in exchange for equity in the companies — around the world. With new capital in the bank and an eager international audience, Behar’s bid to redesign the world is about to go global.

In public Behar speaks softly, and his sentences bear the occasional hesitation of someone for whom English is a second language. (His first is French, and he is also fluent in Italian and German.) In English, Behar will sometimes cut off a sentence halfway through and begin again, or give up after conveying the general idea. Onstage and in interviews, Behar’s attitude is one of polite forbearance — the child made to sit still for a portrait. When he listens, he sometimes removes his Up band and turns it over in his hands. If a question particularly interests him, he grows more animated, illustrating his thoughts with gestures. His hands roll forward like waves, one thought proceeding neatly to the next, a tide of answers coming in to shore.

He grows most animated when discussing the Up, which was among the first fitness trackers of its kind. Most products created by designers are used relatively infrequently by their owners — the lemon zester you buy and then pull out twice a year. But devices tied to smartphones are different. People who wear the Up open its companion app an average of 20 times a week. "Frequency of use is off the charts," Behar says. "It becomes an incredible way for us designers to connect." The technology still feels primitive — the Up tallies things like steps taken or hours slept, and then shows them on a screen. But its wavelike texture and bold colors convey motion in a way that turns the device into a statement. It says: I take care of myself.

Behar believes the future belongs to objects like Up, which give people more control over their lives through sophisticated but subtle applications of technology. He’s broadly interested in "moving design closer to the body," through objects that adapt to you over time. "Our principal role as designers is to accelerate new ideas, and the adoption of new ideas," he says to the audience at Basel. "This is a way to do that."

Behar’s trip to Switzerland is a homecoming; he grew up 120 miles away in Lausanne. Among the attendees of his panel are his parents, Henry and Christine, and an aunt who is visiting from Turkey. Behar’s aesthetic mission has extended even to his parents’ home in Lausanne, where he disliked the chairs so much that he recently told his mother to get rid of them on the promise he would replace them. She complied with this request, but he has yet to replace any of the chairs months later, and if you find yourself introduced to Christine Behar she may relay this information to you within the first few minutes of your conversation. (He has since designed some chairs for her.)

"I never felt truly at home in Switzerland."

Behar’s longtime girlfriend, art advisor Sabrina Buell, is here in Switzerland as well. She’s traveled to Europe with Behar and their daughters, three-year-old Sylver and six-week-old Soleyl. Behar also has a seven-year-old son, Sky, from a previous relationship. (His parents chose a "Y" name for Yves in honor of Henry, and he has continued the tradition with his own children.) Though Behar retains his Swiss citizenship, in most ways he is a fully assimilated Californian: the surfing, the yoga, the utopian embrace of technology. Even his own countrymen can seem wary of him — when Behar checks into his hotel room, which Buell has reserved under her name, the front desk refuses him, thinking him a potential imposter. "The Swiss," Behar says, "can be very difficult."

After the panel, Behar shakes hands with design students from the audience, takes their business cards and autographs a festival program. I had traveled to Europe to see Behar at work, and when he spots me after his talk, he invites me to join as he and his family browse the art collection across Art Basel’s courtyard.

Inside the gallery, a wire sculpture catches Behar’s eye. The untitled work, by the artist Fred Sandback, consists of a piece of elastic cord and steel snaking out of a wall to form a three-dimensional rectangle, 102 inches long, hovering in space. The sculpture, which Sandback completed in 1968, represents the kind of minimalism that is easily dismissed. You could have made that, Behar’s mother says to his father in French. But to Behar, the wire resonates because of its radical simplicity. It is, he says, something to aspire to. "It’s about creating a maximum effect with the lowest means," he says. The work reminds him of his earliest days as a designer, when he couldn’t always afford the materials he wanted, forcing him to improvise.

"It’s an ambition to make design central to more businesses."

The wire sculpture’s price tag is $450,000. Behar’s father, who is 75, makes a face and sighs. "I must be getting very old," he says.

Henry Behar comes from a family of Sephardic Jews who were forced out of the Jewish ghetto in Venice and settled in Turkey. Christine Behar grew up in East Germany, and at the age of 17 escaped into West Berlin via an underground tunnel. They met at a nightclub in London, and married in 1966. Yves was born a year later. As a child, he often played with a hand-me-down Lego set given to him by a cousin. He built houses from the plastic bricks, growing frustrated whenever his creations failed to achieve a perfect symmetry. Behar says he wanted them to look "resolved." That play evolved into frequent teenage tinkering in his parents’ garage, and at 16 he decided to pursue design. Three years later he enrolled at the Swiss branch of the Art Center College of Design. By then, he was chafing against his Swiss surroundings: the country seemed increasingly small and closed-minded to him. "I never felt truly at home in Switzerland," he says. He transferred to the main branch of the Art Center in Pasadena, California in 1990.

At the time, Behar saw California as little more than a way of escaping Switzerland. But his timing was impeccable. He arrived just as desktop computers were coming to the fore, and Silicon Valley manufacturers were looking to industrial designers to differentiate their anonymous beige PC towers. Upon graduation, Behar moved to San Francisco, where he worked as a junior designer at big firms Lunar Design and Frog. (Among other desktop designs, he worked on the award-winning Pavilion from Hewlett-Packard.) Along the way, Behar absorbed Silicon Valley’s genetic optimism about the social impact of technology. It has since become a hallmark of his work. "Hollywood tends to have a dystopian view of technology — I think it sells more movies," Behar says. "But I can’t escape the environment I’m in, which is San Francisco, which tends to think in a utopian way about technology. It certainly makes mistakes, but I tend to have a positive view of it."

Behar founded Fuseproject in 1999, with the aim of serving clients who understand what good industrial design can do. The firm’s early work included a perfume bottle, a shampoo bottle that he designed for his hairstylist, and a recycleable shoe with an intuitive microchip designed for an exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. The shampoo bottle won a design award, and the shoe brought Behar wide attention. His roster of clients multiplied, and in 2004, just five years after starting his own firm, he had solo shows at SF MOMA and in Lausanne.

As the demand for Behar has grown, Fuseproject has swelled to more than 70 employees. If you value thoughtfully designed tools and have some disposable income, there’s a decent chance that something from Yves Behar’s imagination is in your house, in your office, or on your wrist. Along the way Behar has become a wealthy man, although it’s hard to say exactly how wealthy: the startups he has worked with most closely have yet to go public. He stands to make millions from the partial sale of Fuseproject, and will remain CEO, promising that very little will change in the day-to-day running of the company. "Overall," he says, "it’s an ambition to make design central to more businesses. And it’s a recognition that there’s much more work to do in that sense, internationally."

"What Yves is really good at is asking questions relentlessly," says Jason Johnson, his co-founder at August, a home automation company. "He will just ask, ‘Can we make this a little bit smaller? Can we make this a little more fluid?’ He will ask questions that will force the people in the room to either say, ‘No,’ or, ‘That’s impossible,’ which he’ll challenge."

Gilles BianRosa, who hired Fuseproject to design the Fan TV set-top box, watched Behar throw out a design for the accompanying remote control the team had worked on for months. The remote felt great to hold, but problems with the materials interfered with the box’s electronics. After puzzling over a solution, Behar told everyone they would have to start over. "I remember Yves’ team looking at him and saying, ‘Holy shit!’" BianRosa says. "Even my own team looked at him thinking, ‘What?!’ Because it was crazy for both our timeline and Fuseproject’s timeline. And yet we said fuck it, we’re doing it from scratch. If we’re trying to invent the remote of the future, we’re not going to compromise."

"If Yves doesn't threaten to quit on a project, that means we’re not doing our best work."

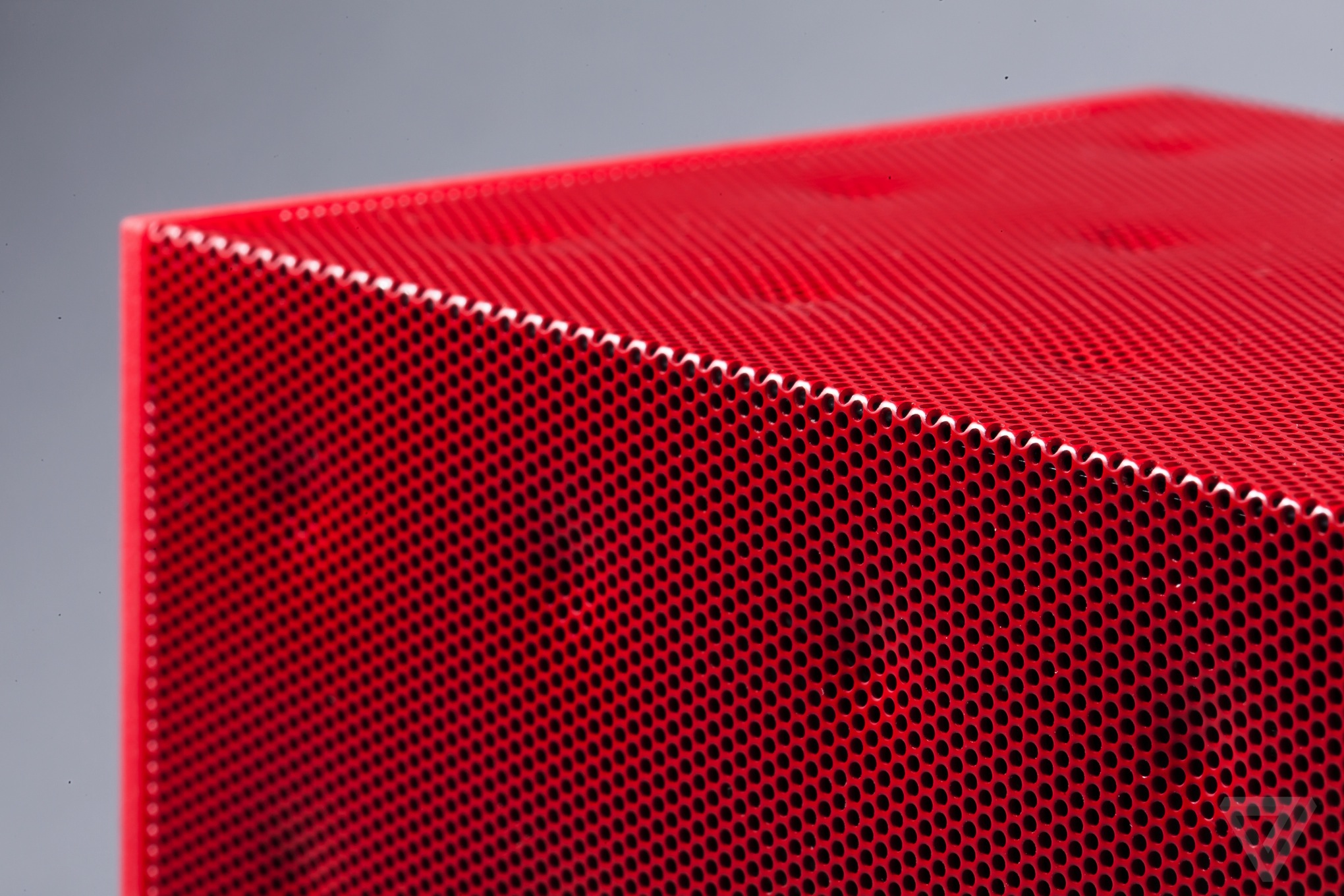

Of course, nearly every design winds up being a compromise of some sort. The plastic you want turns out to be too expensive, or the casing needs to be bigger to fit all the sensors, or there’s a seam running along the bottom because working from a single sheet of metal proves to be impossible. (The seam underneath the Big Jambox, which is the first Behar object I ever bought and still probably my favorite, continues to bother him.) In the case of the final Fan TV remote, though, any compromises are obscured. It’s a glossy, white, touch-enabled pebble that fits neatly in the hand. It snaps, via magnet, onto the accompanying set-top box, and the shape of the remote mirrors that of the box. Behar objects often make ingenious use of textures, causing their look to change slightly depending on the light. The result is often a thing you feel compelled to touch. Most remote controls you want to hurl across the room in frustration; this one you want to slip in your pocket.

Johnson, of August, says Behar is successful because of his poise. "He’s very in control emotionally," he says. "Because he’s not raising the temperature of the room, nobody else does, either. You never get into a shouting match." But Hosain Rahman, the founder of Jawbone, says Behar can be combative. "I don’t qualify him as zen or docile," Rahman says. "We have a great relationship, but we can fight. I used to tease people that if Yves doesn’t threaten to quit on a project, that means we’re not doing our best work."

Behar, who is Jawbone’s chief creative officer, allows that he and his Fuseproject colleagues "are not known as being yes-men and yes-women." "I don’t think you can practice what we do without a strong vision," he says. When he meets with resistance, he often tells his clients that "there is no time for average work." Behar also repeats the mantra Pixar adopted when it decided to rewrite Toy Story 2 from scratch eight months before its release: Pain is temporary, but suck is forever. When a design finally comes together, he says, "the pain is forgotten. What lasts is the quality of the work."

After spending the weekend in Lausanne, Behar flies to London on Monday morning for two days of meetings. Around noon, he stops at the Ace Hotel in central London for lunch with Lucas Dietrich, the long-suffering editor of his book project. Dietrich, an American who works at the art-focused publishing house Thames and Hudson, has been working with Behar on a retrospective of his design work that will showcase its impact around the world. Dietrich’s pitch to Behar was somewhat unusual — "I said, this will be agony for you and me both," he recalls — and Behar agreed. That was seven years ago.

Behar flatly rejects the latest designs for the book, which he reviews on his iPhone: it looks too much like a documentary of his design process, he says, and not enough like a magazine spread. He would like it to look more "editorial." Dietrich nods vigorously and assures Behar it will be handled.

A taxi takes Behar across town to meet Nadja Swarovski, an executive at the family-owned crystal empire that bears her name. Swarovski, who was raised in Europe and America, is beloved among designers for her willingness to spend big on custom art projects to promote the family brand. In 2007, Behar designed a chandelier of 16,000 Swarovski crystals that changed shape when you traced your fingers along a nearby touchpad. Later, he designed an environmentally friendly chandelier consisting of a single crystal illuminated by an LED light. Along the way, he and Swarovski have become friends.

Swarovski greets Behar with a hug, her hand revealing a ring with a crystal the size of an unshelled walnut. They talk of her recent purchase of a home in suburban London — it’s close enough to the country club that she can have meals sent over to the house. But soon they get to the point: Swarovski wants to discuss an exhibition for the London Design Festival in September. She would like it to involve drones. Behar lays out a vision involving a dozen or so autonomous drones, laden with Swarovski crystal, circling in formation above the courtyard of the Victoria and Albert Museum at night. The drones will move in a programmed ballet, ultimately uniting to form a temporary chandelier, lit up and spinning above the heads of festivalgoers. Swarovski loves it.

A few minutes into the conversation, a severe-looking woman named Irene Schiebel steps into the conference room. She has been summoned in the hopes that her family’s drone business, which is based in Austria, can supply vehicles for Behar’s aerial ballet. Behar asks about the types of drone that Schiebel has available. "We have one drone," she says, curtly. This would be the massive Camcopter S-100. With a wingspan of more than 11 feet, and a price upwards of $4 million, it’s immediately clear that Schiebel’s product is both too large and too expensive for their needs.

Swarovski frowns, but Behar humors Schiebel with more questions. Finally, Swarovski says they’ll call her later in the week. Schiebel, stonefaced, says her week is very busy, as is next week, and that afterward she will be on vacation for the rest of the summer. She has no questions about the scope of the project, and seems vaguely annoyed at being asked to attend the meeting. When she leaves the room, Behar and Swarovski look at one another in wonderment. "That was phenomenal," Behar says.

From there they share a cab to the museum, where they are to meet with various officials about drone logistics. A burly gentleman who runs an aerial photography company leads the conversation. Ruddy-faced and shaped like a bowling ball, he quickly knocks down Behar’s ideas. No, you cannot program the drones to fly autonomously — too dangerous. No, they cannot circle majestically overhead — they must be protected from the crowd by a large net. As the dream of a drone chandelier falls apart, Swarovski makes a pained expression, and leaves the gathering to get some air. Behar remains calm, asking questions in hopes of devising a workable alternative, before requesting more time to think. As he goes to offer a parting thought, the drone man interrupts again. "One more thing to think about," he says, and points to the cloudy London sky. "These things don’t do rain."

On Tuesday morning, Behar walks a short distance from his London hotel to the Royal College of Surgeons, where Herman Miller is staging an event. Miller is a 108-year-old company that has no in-house designers; instead it contracts with a handful of marquee talents around the world. The most famous of these were the modernists Charles and Ray Eames, who rose to prominence in the 1940s and ’50s after pioneering the use of molded plywood, fiberglass, plastic resin, and wire mesh in their furniture. Charles Eames is a source of enduring inspiration to Behar, who often quotes one of his mottos: "The best for the most for the least." (He never quotes another of Eames’ mottos: "Innovate as a last resort.")

On this day, Behar is presenting his new line of furniture to 180 Herman Miller sales executives from around the world. In back-to-back, hour-long lectures, Behar lays out the Living Office, a suite of furniture designed to encourage collaboration. Its centerpiece, the social desk, includes a seat at every workstation that invites a colleague to sit down. In his team’s investigations of modern work, Behar found that 70 percent of office collaborations happen deskside, even though desks often lack seating for a second person. So Fuseproject designed a set of furniture, based largely on its own working patterns, to facilitate quick check-ins.

"I'm interested in being the best partner. The best collaborator."

Behar is a low-key salesman. His presentation is filled with slides from his own office, where his team has been testing the prototypes extensively over the past year. He methodically shows the evolution of the desk from cardboard prototype to finished project, emphasizing how they encourage collaboration.

Herman Miller is an ideal partnership for Behar: it gives him creative freedom, it’s lucrative, and it burnishes his design credentials. When the day is done, in the back of another taxi, Behar says he ultimately wants to be known as someone who brings projects like this to life. "For me, it’s not about being the best designer," he says. "I’m interested in being the best partner. The best collaborator." Behar has been asked many times to become an in-house designer, including by what he describes as "grade-A" technology firms, but has always declined in order to maintain his creative freedom. (He won’t say which companies approached him, but if you ask if Apple is among them, he will make a tortured face and quickly change the subject.)

The taxi pulls up at the Serpentine Gallery in Hyde Park. For the past 14 years, the gallery has chosen relatively unknown artists to build sculptures on its grounds. Previous honorees have included Frank Gehry and Rem Koolhaas; this year the gallery chose Smiljan Radić, a Chilean architect best known for his unusual houses. Tonight is the installation’s opening, and the London art world has turned out for the occasion. Radić’s creation is a large, khaki-colored, vaguely organic form with openings cut at odd angles. Just inside, rope lighting zig-zags overhead, giving Radić’s structure the impression of a nightclub fashioned out of a giant mushroom.

Behar is well known to many in the crowd, including a handful of journalists, who buttonhole Behar with tape recorders to ask him his thoughts on the structure. (He likes it.) Behar chats happily. His shoulders relax, and he smiles easily and trades stories with his fellow guests over a glass of pinot grigio.

An archetypal London rainstorm breaks out, drawing everyone back into Radić’s mushroom. Soon, a small crowd has gathered around Behar, who is talking once again about the future, and the incredible power that devices with embedded sensors will soon have to make us feel better and live longer. Behar talks about his father’s asthma, and how doctors say physical activity can improve the condition. "But nobody checks whether you’re physically active!" Like so much in the present day, this simply will not do. Behar raises his hand to reveal the Up band on his wrist. He points at the band and grins ear to ear, as the crowd leans in. "With this," he says, "it’s easy!"

Photography by Ike Edeani. Product photography by Michael Shane

Check out a gallery of Yves Behar's 12 most stunning designs here!

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/71361030/edeani_2014_vergebehar_01-horiz.0.1408646757.0.jpg)

Loading comments...