Mexico City rooftops – azoteas – are usually flat. A parapet wall encloses the roof area, creating a kind of open-air patio, less visible to neighbours than the common interior patios of colonial and neocolonial buildings, and not easily accessed by visitors.

The rapidly expanding city of the 1920s housed its working classes either in these small rooftop rooms (cuartos de azotea), or in the more well-known vecindades, Mexico’s version of tenement buildings. Brought to Mexico during the conquest in the 16th century, but transformed into the sort of living quarters we know today during the mid-19th century, the vecindades were the typical dwelling space for working-class families, and in them the urban lumpen were crammed into small rooms that surrounded a common patio. While these were occupied by members of the working classes whose jobs did not provide room and board, such as factory workers, builders, or street-vendors, the cuartos de azotea were occupied by maids and servants, usually migrants from the provinces, who worked for the family that lived downstairs.

Unlike the vecindades, which remained segregated and were always a space for the working classes and urban lumpen — even if they were appropriated as icons and romanticised by the middle and upper classes — the azoteas began to be inhabited by members of the middle-class intelligentsia during the early 20th century. All over downtown Mexico City — which the middle and upper classes had begun to abandon in order to move to wealthier, more modern colonias nearby — artists, writers and intellectuals started renting or simply occupying small rooftop rooms. Alfonso Reyes, for example, lived and worked in a rooftop room in Avenida Isabel la Católica around 1908. From there, he wrote one the earliest “panoramic” portraits of the city seen from an azotea:

“Come Sundays, and the high windows, what with the red light that they reflect, look like entrances to burning furnaces; just when the sun becomes more endurable and drags its horizontal rays across the city, the people of Mexico appear on the rooftops and give themselves to contemplating the streets, to looking up at the sky, to spying on the neighbouring houses, to not doing anything (…)

It is then when the bored emerge to the rooftops, men who spend long hours reclined on parapets, looking at a tiny figure that moves around in another rooftop, on the horizon, as far as sight can carry. Other times it is groups of young men who improvise platforms upon the irregular surfaces of the rooftop and talk and laugh with sonorous cries, feeling perhaps, at this height, somewhat liberated from the burdensome human environment, and whose demeanour is tinged with familiarity by their moving around in shirtsleeves – as on a rooftop no one is ashamed of exhibiting themselves dressed like this.”

It would take at least another decade before rooftop living consolidated as a common model among the urban middle-class. But by the early 1920s, it was clear that rooftops had been taken over. Among the known trespassers of the city’s rooftops of those years are the American anthropologist and editor Frances Toor, Italian photographer Tina Modotti, American photographer Edward Weston, Mexican painter Dr Atl, the painter, poet and model Nahui Ollin, muralist and painter Roberto Montenegro, Mexican poets Xavier Villaurrutia and Salvador Novo, or the painter Joaquín Clausell.

They were all trespassers in the sense that they crossed the boundary of rigid social-class demarcations and occupied the space of the lower classes. But also, in the sense that they crossed over the line of the acceptable literary and visual culture and brought the Mexican modern movement into being. What was it about rooftops that made them so attractive to this young, national and international, modernist intelligentsia? Were these bohemian rooftop-dwellers merely “ur-hipsters”, or antediluvian beatniks, allured by the aesthetics of self-induced poverty? Or did the appeal of the almost invisible “upstairs” and the appropriation of azoteas by the middle-class have deeper social causes?

What follows is a kind of “map” of the cuartos de azotea, in or near downtown Mexico City, in which writers, painters, photographers, translators and editors lived and worked during the 1920s. Their old rooftop addresses head each of the sections – so that the curious Mexico City flâneur may visit them and perhaps, if he or she is lucky, even climb up to the top.

Uruguay 170 And 5 De Febrero 18: Dr Atl And Nahui Ollin

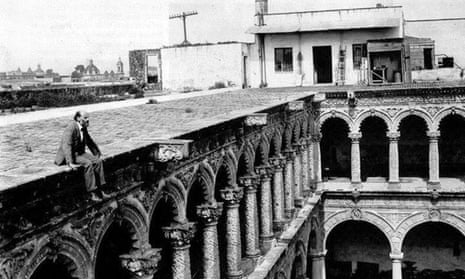

Some of the most intriguing rooftop images of the early 1920s are anonymous, and were taken in the former convent La Merced, when Dr Atl moved into its rooftop room in 1920. In the above picture of him sitting on the border of the rooftop, legs dangling in the heights, we can see his cuarto de azotea at the back, with its tinaco (water tank) on top. Beyond the room, to the left, we see a series of church cupolas — the highest structures in the Mexico City of the early 1920s.

Dr Atl is better known for his work as a landscape painter who portrayed the horizons of the valley of Mexico. In earlier days, however, he was also heavily invested in revolutionary politics, and among other things had recruited men to fight in the Batallones Rojos – troops formed of workers which supported the constitutionalist government during the Mexican revolution (1910-1920). He later served President Carranza in his unsuccessful struggle against Alvaro Obregón – as he recalls in his autobiographical novel Gentes Profanas en el Convento, when Carranza was killed in 1920, Dr Atl was imprisoned briefly but managed to escape and hide, living as a homeless man in the streets of Mexico City’s downtown neighbourhood La Merced, barely surviving on rotten fruit which the gangs of street children had taught him to find and pick.

The story of how Dr Atl finally arrived at La Merced is narrated in detail, though perhaps with some poetic licenses, in Gentes Profanas. Apparently one day, while he was loitering on a street corner, a man recognised him and asked if he was the same person who, a decade earlier, had recruited him to fight in the revolution. Dr Atl confirmed. The man, who later introduced himself as Ángel, put himself at his service, saying he was forever in debt to Dr Atl for having given him the opportunity to fight for his country.

Dr Atl, who could barely walk by then – worn down as he was from fatigue and starvation – asked if the man could find him food and a place to stay. It just so happened that Ángel was the portero (doorman) of the half-abandoned La Merced; he told him that there were plenty of rooms in the former convent to choose from. Ángel suggested the rooftop – the rest of the rooms, he said, were haunted by the fearsome ghosts of monks. (Ángel and his family lived in the room closest to the front door on the ground floor, precisely for fear of these ghosts.)

Among the recollections that Dr Atl describes in detail is his first rooftop bath, after months of not having washed himself:

“Isn’t there a place to have a bath here?”

“Sir, there’s nothing here but the big water depository, which is over there, on the edge of the rooftop …”

I waited no longer. In an instinctive impulse I parted from my guardian and walked toward a square tank filled with water, and quickly started to strip myself from my poor vestments.

“No!” he shouted. “That’s the cistern that supplies water to the entire neighborhood!”

That whole maneuver, which had lasted a good amount of time, caught the attention of the people that lived in the houses around the rooftop, and some women started to direct insults at me.

“Pig!” they called out. “How are we to drink now from that filthy water? Pervert!”

Me, a pervert? What could be immoral in a skeleton that exhibits its bones in the rooftop of a convent, under the light of the sun?

Atl is the Nahuatl word for “water”, but Dr Atl’s real name was Gerardo Murillo (he gave himself the name “Atl” in 1902, while living in Paris). This peculiar form of linguistic transvestism – replacing a Spanish name with a name in Nahuatl – could be seen either as a pretentious affirmation of peculiarity or as a playful slap in the face of the elite, which treated Mexico’s indigenous past (and present) with either contempt and shame or paternalistic inclusion.

Dr Atl dedicated his time in the azotea of the ex-Convento de La Merced to two fundamental things: cupolas and copulation. From his azotea, the monotony of the rather low and flat cityscape around him was interrupted only by successive church cupolas, as can be seen in the picture of Atl sitting on the inner border of his rooftop. It was perhaps while looking at the city from his rooftop that he came up with the idea of dedicating an entire book to just surveying and studying church cupolas. But the latter was also indeed a large part of his life during this rooftop period. In those same years, the poet, model and painter Nahui Ollin (sometimes spelled Olin) moved in with Dr Atl, while still married to another man. They had a short but passionate love affair. As he recounts in his autobiographical novel, she spent the days with him painting, writing and sunbathing naked in their azotea, to the consternation and repugnance of the same ladies who had called the then skeletal Dr Atl an immoral pig.

In another anonymous photograph, Dr Atl reads the newspaper and Ollin stands at the threshold of their rooftop room, the age difference between them flagrant. She is wearing an almost infantile white dress, but dark high-heeled shoes and dark tights. Their modest but to a degree fashionable appearance contrasts with the ruinous surroundings: the uneven brick floor, the frail ladder, the mossy walls, the broken windows.

Ollin and Dr Atl had met at a dinner party, while she was married to the painter Manuel Rodríguez Lozano, whom she repeatedly accused of homosexuality during their marriage, and with whom she had a child in France, who had died in early infancy. She left Rodríguez Lozano to live with Dr Atl in La Merced, causing a public scandal second in rumpus only to the scandal caused by their separation, two years later, which included loud public screaming, buckets of cold water thrown at each other, death threats, and defamatory pamphlets pasted on the doors of the ex-convent.

In 1926, after leaving Dr Atl, Ollin moved into another cuarto de azotea, in the second block of the street Cinco de Febrero, number 18. She lived there until 1932. She received visitors such as Tina Modotti, Edward Weston, Jean Charlot and Anita Brenner, who wrote about the space in her diaries, saying: “Nahui lives there, she has a Spanish-type picturesque little house in the rooftop. Flowers, a parrot, dogs, cats, art, and a lot of sunlight … a wonderful place, perhaps too cute. Tina was enchanted.”

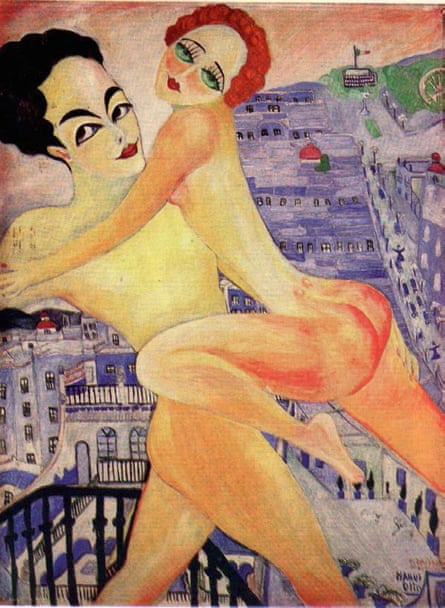

It was in this room that Ollin painted some of her more well-known self-portraits. In these portraits she usually appears naked, sometimes alone and sometimes with a lover, always looking at the viewer directly with enormous cat-like eyes, the tangled city below her. It is interesting that the way in which Mexico City appears below her could easily be any European city, and perhaps particularly Paris. But it is very clearly Mexico City. To the left of the naked bodies is the Paseo de la Reforma, leading to the Chapultepec Castle, the president’s house. Also visible from the rooftop is the Rueda de la Fortuna (fortune wheel) of the Chapultepec Park.

More well-known than her self-portraits, however, are the nude photographs that Antonio Garduño took of her in the mid-to-late 1920s. There were hundreds of these, and in September 1927, Ollin showed a selection of them in a public exhibition at her new cuarto de azotea. She was praised by many but also criticised harshly as a result of this exhibition, as her unapologetic nudity was seen by many as downright profane.

Ollin and Dr Atl are an early example of a kind of social and cultural transgression. Living in a space designated for servants, their appropriated Nahuatl names, their scandalous love affair and days dedicated to painting and writing under the sun was by no means acceptable under the code of conduct of the gente decente (decent people). These gente profana, as the title of Dr Atl’s autobiographical novel boasts, were in a way the foundational couple of rooftop trend, the perverse Adam and Eve of the azoteas. They were among the first in the city to use a rooftop as both an alternative dwelling space, and a space for creative production that contested the moral standards of the times.

The peculiar visibility-invisibility of the rooftop allowed this: removed from the scrutiny of their own social class, they offered an unworried spectacle to the servants of neighbouring houses. At a remove from the city, they seized the freedom to experiment. Liberated from the life of middle- and upper-class interiors, with all its codes of conduct and formalities, they gave new names to each other, and pushed the limits of the dominant morality.

Brasil 42: Salvador Novo, Villaurrutia and Ulises

In a letter dated 14 March 1927, the poet José Gorostiza writes to his fellow poet Carlos Pellicer: “In the building of our poetry [you are] the window: the large open window that looks onto the fields … We are – you know this – the interior rooms, Xavier the dining room. The rest, bedrooms. The one at the very back is Jaime Torres Bodet … Salvador Novo? The rooftop. Linen out in the open.”

The expression trapos al sol, only half-accurately translatable as “(dirty) linen out in the open”, can mean several things. But in this particular context the expression relates to what is made public, but should probably have remained private. Gorostiza is comparing Novo to an azotea, where linen hangs out in the sun to dry; a space where private garments are made public – at least to those who live in other azoteas.

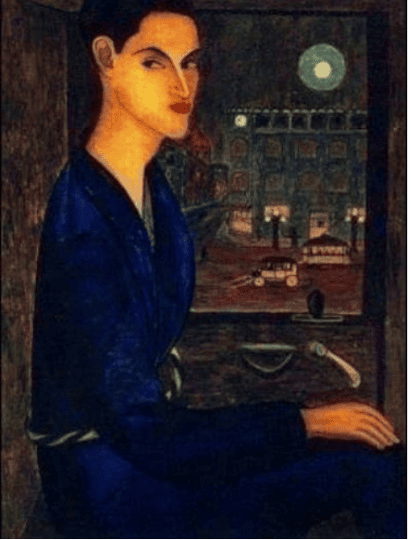

But what is this exposed linen referring to? In 1925, Nahui Ollin’s former husband, Manuel Rodríguez Lozano, painted a portrait of a young Salvador Novo, sitting cross-legged, swathed in a blue robe, looking sideways, as if conscious that he is being looked at by us. What is Novo doing at night, in a taxi, dressed only in a robe? He was parading trapos al sol, no doubt, as Gorostiza had written in his letter to Pellicer.

Although the painting is titled Taxi, and indeed a taxi door divides the interior space we see from the city outside, the perspective used is hardly one that we would see from the vantage point of a taxi on a street. We see the city from above: its cars and streetlights, its tram, its colonial buildings, its rising moon. The corner depicted is recognisable: the building in the background is the Palacio de Correos, by the architect Adamo Boari. The portrait was painted in Lozano’s studio, possibly on a low rooftop in a building on the street then called San Juan de Letrán (most buildings then were no higher than three or four storeys). The particular corner is not just any corner in the city – as Carlos Monsiváis describes it in La Mano Temblorosa de una Hechicera:

“San Juan de Letrán was, back then, not a mere street, it was the center of life in the capital, of the life that was worth living (…) there began and ended the world of the prohibited, of that which only had a place in the sobremesa of solitary men (…) In that street walked drivers and politicians, hookers and women of high society, machos and sissies … I think it was in San Juan de Letrán where gays started coming out of their holes to start moving about, unhindered, and go after whomever allowed it.”

As a young man Novo, later considered one of the major poets of the Contemporáneos generation (the Mexican modernist poets), lived a double, liminal existence between his family’s regime of typical gente decente and the forbidden underworlds of homosexual men in the still highly reactionary 1920s.

In his autobiography, La Estatua de Sal, Novo recounts how, in search of better light for studying, he would often climb up to the rooftop of his uncle’s house, where he lived in the early 1920s. To get to the rooftop, he first had to climb a stairway that led up to a room where the family’s chauffeur, Emilio, had his living quarters. He then had to cross that room — “full of oil cans” — and walk through another door that led to the open azotea.

One day, Novo walked into the room and found Emilio napping on his bed. He silently walked past him and out through the other door to the azotea, where he leaned on the parapet, looking down toward the streets. “Lost in the pleasant absorption of that silence,” Novo recounts, “of the panorama of rooftops sprinkled here and there with the yellowing treetops at sundown,” he suddenly felt Emilio approaching from behind. Emilio embraced him and pressed his body against Novo’s back. They exchanged a few words and caresses, and Emilio led him back to the room.

On that bed, in Emilio’s rooftop room, the young Novo discovered a kind of pleasure that would lead him, over the years, to seek out more encounters with chauffeurs, of whom he particularly cherished the smell of gasoline. Years later, for example, he would fall in love with Arturito, a driver who drove one of the first passenger buses in Mexico City, from downtown to the colonia Roma. Novo would sit next to him on the bus and “inhale, with a retrospective and promissory delight, the emanations of gasoline next to his body”.

Fortunately, Novo’s fetish for drivers was stronger than his infatuation with gasoline. In 1923, he started writing for the newspaper El Chafirete (Chilango slang for chauffeur), destined for the guild of drivers and written in the particular urban jargon that they used. “Some of the best skins around came to me, lured by El Chafirete,” Novo recalls. Indeed, his collaborations in El Chafirete earned him a passport to Mexico City’s gay underworld – or, to be more precise, Mexico City’s upper world: its sordidly thrilling rooftops.

Novo went to school with the city’s intellectual elite in the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria, but, while the other poets of his generation read the French symbolists and drank tea in French-like salons, he frequented the azoteas and, on occasions, the vecindades. In his memoir, he recalls the extravagant nicknames of some of the locas and transvestites whom he frequented: like their cross-dressed bodies, their names were a sort of parodic translation of their caricatured identity. A priest is renamed Mother Demon, the short and squat Carlos Meneses is a “Bottled Fart”, a man is called “Chucha” (female dog), and an aspiring opera singer is Anetta “Gallo” (literally “cock”, but also meaning “false note”).

One of the young poets who eventually crossed over and trespassed with Novo, from the well-to-do world of the urban intelligentsia to the world of the azoteas, was Xavier Villaurrutia. They had met in the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria, and had discovered they shared literary affinities, among other things. Novo introduced him to French and American poets – as well as to La Virgen de Istambul, with whom Villaurrutia had a short affair.

In 1924, Novo decided to rent a cuarto de azotea in the rooftop of an old colonial house in the calle Brasil #42. The room was near the Preparatoria, and also conveniently – for Novo – located near the transit department, always replete with drivers and chauffeurs acquiring or renovating their licenses. Shortly after, Xavier Villaurrutia joined him in another studio in the same rooftop, and later came the painters Roberto Montenegro and Agustín Lazo. In La Estatua de Sal, Novo recounts their collective experiments with sex and drugs, a possibility to which their rooftop studio had opened a door. They hosted drivers, cadets, construction workers, other poets, painters and professors alike. They tried the then-demonised marijuana — Novo remembers only that he immediately passed out. They indulged more frequently in cocaine, which was available by prescription in local pharmacies.

Among the cultural and social transgressions led by Novo and Villaurrutia, a less scandalous but in the long-term more subversive (or establishment-irritating) event took place: Ulises, the first modernist journal, was born. Ulises had nothing to do with the kind of state-sponsored projects going on at the time; it did not advance the revolutionary cause. Much more elitist in its content and target audience, it paid little or no attention to the political struggles of the times. Novo and Villaurrutia published Ulises between May 1927 and February 1928; it was a precursor to the more well-known Contemporáneos, where the first renderings into Spanish of Langston Hughes’s poems, as well as TS Eliot’s The Waste Land, appeared in the late 1920s.

Upon close inspection of the magazine’s masthead, one crucial piece of information, normally ignored, is apparent. Ulises’s postal address reads “Brasil #42-10”. The magazine, it turns out, had its headquarters in one of the rooftop rooms that its editors had been renting since 1924. They met regularly in this cuarto de azotea, with Gilberto Owen too, interrupting their sessions only to eat hot-cakes in a nearby joint called Quick-lunch – an American-style eatery quite different to the French-style salons where other intellectuals gathered, and also radically different to the cantinas and pulquerías that Novo visited in his nightly excursions.

If political heterodoxy had initially marginalised Dr Atl into the space of the azotea, and torrid romances had kept him there, then sexual difference had drawn poets such as Novo and Villaurrutia to rooftops. In a society where there was no moral and physical place for difference, other spaces have to be invented.

In the context of an intensely nationalist and reactionary Mexico, obsessed with the figure of the “macho” and with nation-building discourses and programmes, rooftops appear as heterotopic in the sense that the cultural activities that took place in them both did and did not lie under the umbrella of the state’s nation-building cultural programmes. They were somewhere in-between: Ulises was (secretly) funded by the minister of education, yet criticised heavily by many members of the establishment.

Rooftop rooms were a sort of urban and architectural “absence”, a space of relative invisibility, originally conceived to hide servants from the life of the ruling classes, to conceal them from the rest of the city. They became, with time, a space of transgression for the middle-classes and a certain intellectual bourgeoisie. Magazines such as Ulises perhaps could not have been possible were it not for the freedom conferred by the city’s rooftops. These spaces may have begun as ones for experimentation with drugs and with sexual practices, but they became the sites of alternative modes of cultural production.

Veracruz Esq. Mazatlán: Edward Weston and Tina Modotti

Some of the most well-known rooftop photographs of the Mexican 1920s were taken in Edward Weston’s azotea, upon his arrival in Mexico City in 1922. For some time he shared this space with Tina Modotti, his lover, apprentice and, eventually, co-worker. Like Dr Atl and Nahui Ollin, Modotti and Weston’s transgressive rooftop relationship was something of a public scandal. They were not married to each other, had an “open” relationship, and spent long hours experimenting on their rooftop, either with their cameras, with each other, or with other people.

The historian Mauricio Tenorio-Trillo has fittingly referred to international communism, though we could well extend it to international modernism, as “an erotic mess whose scenarios were Berlin, Moscow, and, of course, Mexico City”. And indeed, the 1920s in Mexico are a period of intense sexual exploration among the intelligentsia, to which Weston surely contributed, but which he also captured and aestheticised through his lens.

The iconic figure of this period of Weston’s work is the nude Tina en la Azotea. In this photograph – of which there exist a few other versions, each only subtly different from the other – Modotti lies horizontally on a jerga. Her body is freely and sensually spread out, gleaming in the sunlight; her feet are full of mud.

Criticism has often focused on Modotti’s naked body itself, as an object of study in the context of Weston’s transgressive photographic work. However, upon closer inspection, one notices that her body creates a peculiar shadow. That shadow bears a subtle but clear similarity to the silhouette of one of Mexico City’s volcanoes, the Iztaccihuatl – also known as La Mujer Dormida (“The Sleeping Woman”). The Iztaccihuatl and its couple-volcano, the Popocatépetl, were visible from rooftops; it is impossible to know if the two photographers were playing on this resemblance intentionally, but the photograph of a napping Modotti can indeed be read as a sort of translation of the view they saw from their rooftop, which they were mapping back on to the floor of their azotea: Modotti, a human-scale copy of La Mujer Dormida.

Tina on the Azotea was shown in Weston’s first solo exhibition in Mexico, in a gallery on calle Madero, in downtown Mexico City. The exhibition must have been a success, as an entry in Weston’s diary on 23 September 1923 states that: “The negatives with Tina as a subject have been a good investment.” Among the Mexican intellectual elite that attended the exhibition were José Vasconcelos and Diego Rivera, who acquired a copy and later used it as a model for one of the female nudes in the Chapingo murals, in the National School for Agriculture. Vasconcelos, on the other hand, who at the time was the minister of education, is reticent about Tina’s freedom and independence. In the third volume of his memoirs, titled El Desastre, he pejoratively nicknames her La Perlotti, and recounts:

“La Perlotti, let us call her thus, practiced the profession of vampire, but without commercialism à la Hollywood and [instead] by a temperament insatiable and untroubled. She was seeking, perhaps, notoriety, but not money. Out of pride, perhaps, she had not been able to derive economic advantages from her figure, almost perfectly and eminently sensual. We all know her body because she served as an unpaid model for the photographer, and her bewitching nudes were fought over.” (trans. Patricia Albers)

In just a few lines, Vasconcelos labels Modotti a vampire, proud, attention-seeking and a quasi-prostitute (“gratuitous model”). The only quality she seems to have, in his eyes, is a sensual body. Modotti must have been viewed in this same way by many other men and women of the time. Like Nahui Ollin, she was transgressive: her beauty, her nudity, her sexual freedom was intolerable for the machos of the revolution – unless they could paint them, as did Rivera; unless they could paint them nude, as also did Rivera, on his luckier days.

In the rigid cultural codes of the early 20th century in Mexico, it was impossible to accept Modotti’s behaviour and to “translate” her into into palatable terms. Modotti, Ollin and, to a lesser degree, Novo (who was ultimately a man and therefore less irritating to those in power), were cast aside and belittled by those who had it in their power to do so.

Abraham Gonzalez 31: Tina Modotti and Frances Toor: Aesthetics Of Revolution?

After Weston’s departure from Mexico, Modotti moved into a building called Edificio Zamora, on the corner of calle Atenas and calle Abraham González, which was so crooked and downtrodden that its residents called it the “Tower of Pisa”. As one of her biographers, Margaret Hooks, writes: “Taking the elevator to the top was likened to riding a cable car up a mountain slope! [Tina’s] love of rooftops led her to turn a servant’s room there into a simple studio, giving her dominion over the azotea with its wonderful views of the volcanoes.”

The other resident of the top floor was the American anthropologist, translator and editor Frances Toor, also known as Paca Toor. She had arrived in Mexico City as one of the American students attending the Escuela de Verano, where Salvador Novo taught. This was a very successful project that linked the National University with American universities such as Columbia or Harvard, and brought students to Mexico to study Spanish but also anthropology, literature, architecture or history.

Unlike most students arriving from Columbia or Harvard to spend a summer in Mexico, Toor stayed on, transforming her sojourn into a life-long project. She became one of the “pensadores rubios”, as Novo used to call, tongue-in-cheek, members of the American intelligentsia who were always “discovering” Mexico. In Del Pasado Remoto, collected in his book Poemas Proletarios (1934), he writes:

“They came in airplanes, the great blond thinkers.

Comfort, said one of them,

Is harmony between man and his surroundings. The Indians, by the door of their huts,

Are more comfortable, bare-foot, Than Anatole France shoe-clad

Or Calvin Coolidge sipping on a Coca-Cola In a salon at the Waldorf Astoria.”

Just as Novo and Xavier Villaurrutia edited Ulises on the rooftop of a building, Toor edited Mexican Folkways in her own azotea between 1925 and 1937. As she states in her editor’s forward to the first issue, Toor decided to publish a bilingual journal because she intended the magazine to be read by “high school and University students of Spanish … as well as to those who are interested in folklore and the Indian for their own sakes.” She adds: “Moreover, much beauty is lost in translating.”

Toor presents herself as a competent cultural translator, should there be any doubt on the part of her readership. In her editor’s forward in the first issue, she states: “Mexican Folkways is an outgrowth of my great enthusiasm and delight in going among the Indians and studying their customs. I have gone alone among them, under circumstances that even my cultured Mexican friends consider dangerous, and in spite of the Indians’ just mistrust of the white stranger, I have never had occasion not to feel safe and at home.”

Unlike Novo and Villaurrutia, who saw themselves as members of the international modernist circuit — looking beyond their azotea to London, Paris, Rome and of course New York – Toor’s project perpetuated a version of Mexico as a non-western, exotic society. So it may seem curious that Tina Modotti became one of Mexican Folkways’s official photographers. Modotti’s early work had stood out precisely because she preferred documenting the Mexico of the urban, technological revolution to the folkloric representation of Mexico, filled with cacti and the barefooted people. But, especially toward the end of the 1920s, her personal and political project as a photographer committed to bringing to public attention the causes of socially and politically marginalised groups, perhaps met up with Frances Toor’s own version of indigenismo.

In 1927, moreover, Modotti joined the Mexican Communist party, and also started publishing her work in cultural magazines with political commitments and agendas — radical publications such as El Machete. What Modotti brought to Mexican Folkways was her radically modernist eye, now focused more on the working classes than on buildings and technology.

Manifestación de Trabajadores, one of Modotti’s most emblematic pictures of the period, is possibly taken from a rooftop, judging by its angle. If so, it may be the rooftop she shared with Frances Toor on calle Abraham González, where she was living at the time. It combines her typically modernist aesthetics – clean lines, patterns, a certain remove – with her growing interest in revolutionary politics. We don’t see any of the workers’ faces, only identical white hats.

The photograph, thanks to the particular distance and angle that the azotea offers, is a sort of abstraction of a march or parade. Modotti had found a way of looking through her camera at the social and political consequences of the Mexican revolution, and in doing so created a modernist aesthetics of the post-revolution.

Rooftops retrouvé

During the early 1920s in Mexico, as the revolutionary government settled into power, the Mexican state and its associated artists and intellectuals began to search for new forms in architecture, literature and art that would represent Mexico and “Mexicanness”, whatever that meant. The state’s “official artists”, such as muralists Rivera, Siqueiros and Orozco, sung the praises of the revolutionary government; architects such as Manuel Amabilis and Obregón Santacilia designed buildings that captured the nation’s “spirit”; and writers such as Manuel Maples Arce represented the cusp of the much sought-after synthesis of modernity and tradition. All of them advanced and upheld (for a time, at least) the causes of the revolutionary government – which in 1946 would crystallise into the Partido Revolucionario Institucional, or Institutional Revolutionary Party, an oxymoron that explains far too many things about Mexico.

The “rooftop bohemia”, in turn, did not always comply to the standards of the government’s plans and programmes – rooftops often engendered a poetics of transgression. Indeed, in the late 1920s and early 30s, during the period known as the “Maximato” – when Pascual Ortiz Rubio became president but, de facto, the authoritarian Plutarco Elías Calles controlled the government – many of these rooftop dwellers came to be seen not only as transgressive, but downright unwelcome in the country.

Modotti was expelled from the country in 1930 for her communist affiliations, and under the false accusation that she had been involved in an attempt against President Rubio. Carlton Beals, a journalist and contributor to Mexican Folkways, was also expelled. Frances Toor, whose work had always been supported or at least tolerated by successive governments, began to fear that the new, highly conservative and anti-left government would close down her Mexican Folkways, as El Machete had been closed down by the government in 1929 (though it continued to be published, illegally, from 1929 to 1934).

Rooftops and their dwellers were not necessarily divorced from what was happening within the other layers of the city, but they offered the possibility of contesting and inverting what took place in “real” or “official” sites. And, in doing so, they allowed their inhabitants to enact a kind of modernist utopia in which gender restrictions were challenged, sexual norms transgressed, moral codes broken, aesthetic principles overturned, and intellectual affiliations reinvented. What is at the heart of the matter is that rooftops allowed a peculiar distance from which a kind of strangeness is established with the city, and from which the city could be viewed, inhabited and ultimately represented and aestheticised.

If we think of Mexico City in terms of its many horizontal layers – ground floor, first floor, second floor – then the layer that in the 1920s stretched out horizontally at about 15 metres above the ground, can be thought of as a kind of semi-invisible, experimental laboratory for modernist creativity and its shifting of moral parameters. The relative invisibility, both physical and cultural, of rooftop rooms allowed an alternative way of life and, concomitantly, a form of cultural production that pushed the boundaries of Mexican literary and visual culture.

Although the new azotea trespassers, these middle-class transplants to rooftop-dwelling, could not actually see each other from their respective rooftops, the fact that a group of diverse but to a degree like-minded people were living and producing work at that particular level, at that particular height of the cityscape, must have had an effect on how they all imagined their place in the city. Even if Modotti, Weston and Toor, Novo and Villaurrutia, Dr Atl and Ollin may not have always crossed ideological and aesthetic paths, they knew each other and of one another, and each knew that the other was playing out their daily life at a similar height, in similar spaces.

For minds that are habituated to thinking of living in terms of its possibilities of representation – narrative, poetic, pictorial, photographic – space is more than just the barren grounds in which daily life and daily work happen be. Thus, at least in a purely symbolic plane, these rooftop dwellers may well have imagined themselves as intermediaries, placed as bridges between the “inside” and the “outside” of the city. Their work – modernist journals, translation magazines, photographic or pictorial portraits, events depicted in abstracted photographs of the city below – responded to the condition of the liminal place they chose to inhabit, both physical and intellectual.

In this sense, rooftop-dwellers can be seen, too, as translators: bridging the gap between inside and outside, between the English and the Spanish-speaking world, between the Mexican indigenous population and the Mexican elite, between the local and the foreign. Whatever their own particular endeavours, together they played a part in the making of international modernism in Mexico.

Valeria Luiselli was born in Mexico City in 1983. Her novels and essays have been published in magazines and newspapers including the New York Times, Granta, and McSweeney’s. In 2014, she was named as one of the 20 best Mexican writers under 40 and received a National Book Foundation award.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion