Why American Jews Eat Chinese Food on Christmas

A lack of dining options may have started Jewish Christmas, but now it’s a full-fledged ritual.

If there’s a single identifiable moment when Jewish Christmas—the annual American tradition where Jews overindulge in Chinese food on December 25—transitioned from kitsch into codified custom, it was during Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan’s 2010 confirmation hearing.

During an otherwise tense series of exchanges, Senator Lindsey Graham paused to ask Kagan where she had spent the previous Christmas. To great laughter, she replied: “You know, like all Jews, I was probably at a Chinese restaurant.”

Never willing to let a moment pass without remark, Senator Chuck Schumer jumped in to explain, “If I might, no other restaurants are open.”

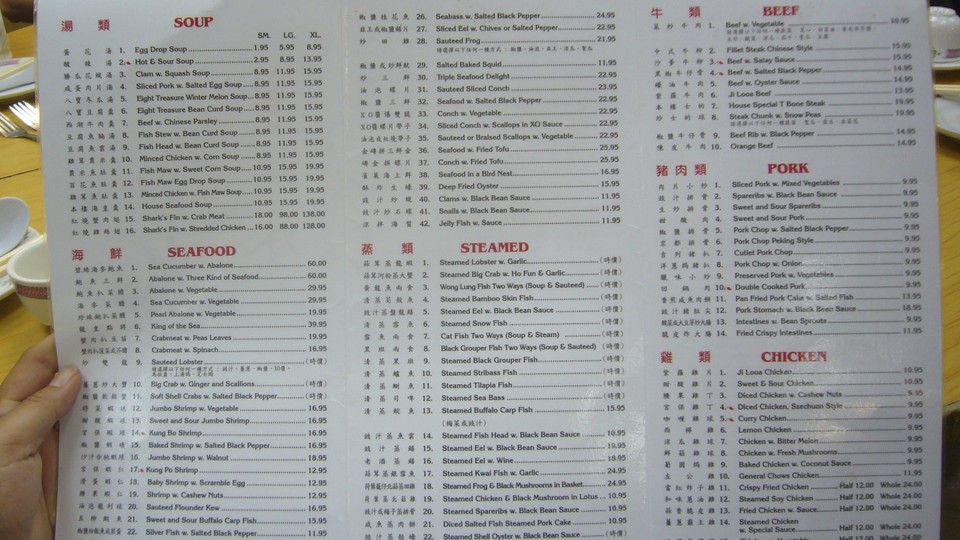

And so goes the story of Jewish Christmas in a tiny capsule. For many Jewish Americans, the night before Christmas conjures up visions not of sugar plums, but of plum sauce slathered over roast duck or an overstocked plate of beef lo mein, a platter of General Tso’s, and (maybe) some hot and sour soup.

But Schumer’s declaration that Jews and Chinese food are as much a match of necessity as sweet and sour are, is only half the wonton. The circumstances that birthed Jewish Christmas are also deeply historical, sociological, and religious.

The story begins during the halcyon days of the Lower East Side where, as Jennifer 8. Lee, the producer of The Search for General Tso, said, “Jews and Chinese were the two largest non-Christian immigrant groups” at the turn of the century.

So although it’s true that Chinese restaurants were notably open on Sundays and during holidays when other restaurants would be closed, the two groups were linked not only by proximity, but by otherness. Jewish affinity for Chinese food “reveals a lot about immigration history and what it’s like to be outsiders,” she explained.

Estimates of the surging Jewish population of New York City run from 400,000 in 1899 to about 1 million by 1910 (or roughly a quarter of the city’s population). And, as some Jews began to assimilate into American life, they not only found acceptance at Chinese restaurants, but also easy passage into the world beyond Kosher food.

“Chinese restaurants were the easiest place to trick yourself into thinking you were eating Kosher food,” Ed Schoenfeld, the owner of RedFarm, one of the most laureled Chinese restaurants in New York, said. Indeed, it was something of a perfect match. Jewish law famously prohibits the mixing of milk and meat just as Chinese food traditionally excludes dairy from its dishes. Lee added:

If you look at the two other main ethnic cuisines in America, which are Italian and Mexican, both of those combine milk and meat to a significant extent. Chinese food allowed Jews to eat foreign cuisines in a safe way.

And so, for Jews, the chop-suey palaces and dumpling parlors of the Lower East Side and Chinatown gave the illusion of religious accordance, even if there was still treif galore in the form of pork and shellfish. Nevertheless, it’s more than a curiosity that a narrow culinary phenomenon that started more than a century ago managed to grow into a national ritual that is both specifically American and characteristically Jewish.

“Clearly this whole thing with Chinese food and Jewish people has evolved,” Schoenfeld said. “There’s no question. Christmas was always a good day for Chinese restaurants, but in recent years, it’s become the ultimate day of business.”

But there’s more to it than that. Ask a food purist about American Chinese food and you’ll get a pu-pu platter of hostile rhetoric about its inauthenticity. Driving the point home, earlier this week, CBS reported on two Americans who opened a restaurant in Shanghai that features American-style Chinese dishes such as orange chicken, pork egg rolls, and, yes, the beloved General Tso’s, all of which don’t exist in traditional Chinese cuisine. The restaurant gets it name from another singular upshot of Chinese-American fusion: Fortune Cookie.

Schoenfeld, whose restaurant features an egg roll made with pastrami from Katz’s Deli, shrugs off the idea that Americanized Chinese food is somehow an affront to cultural virtue. “Adaptation has been a signature part of the Chinese food experience,” he said. “If you went to Italy, you’d see a Chinese restaurant trying to make an Italian customer happy.”

That particular mutability has a meaningful link to the Jewish experience, the rituals of which were largely forged in exile. During the First and Second Temple eras, Jewish practice centered around temple life in Jerusalem. Featuring a monarchy and a high priesthood, it bears little resemblance to Jewish life today, with its rabbis and synagogues.

So could it be that Chinese food is a manifestation of Jewish life in America? Lee seems to think so. “I would argue that Chinese food is the ethnic cuisine of American Jews. That, in fact, they identify with it more than they do gefilte fish or all kinds of the Eastern Europe dishes of yore.”

Over the centuries, different religious customs have sprung up and new spiritual rituals have taken root, many of which draw on the past. Jewish Christmas, in many ways, could very much be seen as a modern affirmation of faith. After all, there are few days that remind American Jews of their Jewishness more than Christmas in the United States.

Adam Chandler is a former staff writer at The Atlantic. He is the author of Drive-Thru Dreams: A Journey Through the Heart of America's Fast-Food Kingdom.