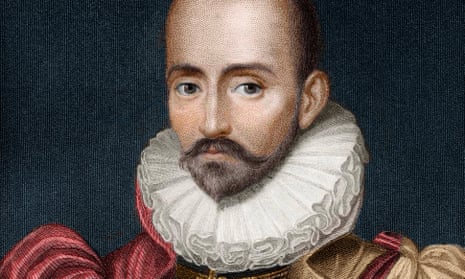

The streets of America may be “haunted by the ghosts of bookstores”, with writers hovering “between a decent poverty and an indecent one” as Leon Wieseltier suggests, but even as the internet has wreaked havoc on literary culture, American women have been fomenting a renaissance in the essay. Leslie Jamison, Meghan Daum, Rebecca Solnit, Roxane Gay and Maggie Nelson are just some of a new band of writers who have taken Montaigne’s project to know the self into the digital age.

Just look at Gay, who won the PEN Center USA’s Freedom to Write award earlier this week, a writer who built her career from contributing to sites such as Htmlgiant and the Rumpus. Her work ranges from literary criticism to critiques of rape culture to the political responsibilities of being a writer and intersectionality. Her writing about pop culture resembles the “thick description” pioneered by anthropologist Clifford Geertz. One of the hallmarks of Gay’s writing is a combination of justified anger and personal vulnerability which resonates with the reader. In 2012, in response to commenters who wanted to hold an 11-year old-girl culpable for her gang rape by 20 men, she wrote:

Maybe we don’t know how to talk about children or even think about children because we don’t want to remember how little we once knew or face how much we would someday know.

Solnit had already published books about conflict in the American west, landscape and gender, but it was her essays on the political blog Tomdispatch that set her flying. She started with a piece about the fallout (pun intended) from nuclear testing in Nevada, but as one of American culture’s true polymaths, her work ranges from nature to feminism, from urban renewal to the overreach of government intelligence gathering, and beyond. Passion infuses her work, and the range of her knowledge astounds, but it is the poetry in her prose that really astonishes:

Creation is always in the dark because you can only do the work of making by not quite knowing what you’re doing, by walking into darkness, not staying in the light. Ideas emerge from edges and shadows to arrive in the light, and though that’s where they may be seen by others, that’s not where they’re born.

These days it’s easy enough to find Solnit and Gay in literary magazines, but many of their readers have only ever encountered them on the internet. Not only has the internet provided a host of sites where the essay is queen – places such as the Millions, the Rumpus, Talking Writing, Literary Hub, and the Awl – but it has also fostered a new kind of reading. The web may distract with shiny clickbait, but the interconnections that send you from reading about, say, being a volunteer in medical exams to the trees growing in abandoned office buildings, give writers such as Solnit and Gay another route to finding an audience. Every time another writer cites their work and links to it in constructing an argument, a new reader is just a click away. Think of how many people first came to Solnit through her account of mansplaining.

Way back before the dawn of Netscape Navigator, the future for public intellectuals looked grim. The academy was clotted with jargon that excluded all but the privileged few. They read each other’s essays, but the rest of us did not. The internet provided the space where writers could re-establish the essay’s importance to the general reader. Montaigne’s project was a call to arms for writers such as Leslie Jamison, who wrote:

Sure, some news is bigger news than other news. War is bigger news than a girl having mixed feelings about the way some guy slept with her and didn’t call. But I don’t believe in a finite economy of empathy; I happen to think that paying attention yields as much as it taxes. You learn to start seeing.

If the digital rebirth of the essay can teach us to see, can help us to expand our sympathies, then maybe the disruption that Wieseltier laments will leave literary culture standing after all.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion