LONG BEACH, Calif.—What are the school colors? Is the whole school free? What happens if you miss a class? Is there detention? How many books are there in the library?

These were just some of the questions eager Long Beach Unified School District 9- and 10-year-olds tossed during their Long Beach City College tour last spring. Their student tour guide, Ashley Martinez-Munoz, a graduate of Long Beach schools herself, took each question from the Madison Elementary School students seriously.

After all, the goal of the tour was to make these fourth graders—many of whom come from families with no history of going to college—comfortable with the notion that they could earn a college degree, whether or not their parents did, as long as they’re willing to work for it.

“I’m one of the first ones [in my family to go to college],” said Martinez-Munoz, 21, now a student at the University of California, Los Angeles. “I try not to talk about it because I feel like I’m bragging. But I’m really proud.”

Arie’ann Velasquez, 10, was convinced. Walking around the landscaped community-college campus, she said the whole do-your-homework-go-to-college thing was starting to seem like a pretty great idea. “It’s my first time being at a college and I’m amazed at what I’m seeing,” Arie’ann said. “It’s huge!”

Every fourth-grade student in Long Beach’s public schools attends a tour like this and all fifth-graders visit California State University, Long Beach, known as Long Beach State. The tours are just one example of the many ways the three biggest public-education systems in this working-class, seaside California city cooperate. Long Beach City College, Long Beach State, and the Long Beach Unified School District have cooperated for about two decades on initiatives like early college tours, targeted professional development for teachers, and college-admissions standards that favor local students.

The results have been so stunning that the city was cited by state lawmakers as a model last week when they unveiled a legislative package called the California College Promise. Were they to pass, the collection of bills would make several of Long Beach’s practices into state policy with the aim of seeing more California children to and through college.

“Poverty needn’t be destiny,” Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom said of the proposed laws, who led a similar collaboration during his tenure as the mayor of San Francisco. “With this legislative package, we’re scaling statewide, with regions rising together.”

In Long Beach, student test scores, AP-class enrollment, high-school graduation rates, and college-attendance rates have all risen, even as the city’s challenging demographics remained almost unaltered. According to California Department of Education data for 2014-15, 68 percent of Long Beach students qualified for free or reduced-price lunch, a federal measure of economic need. That percentage has barely changed since the state began tracking it. And the number of minority students has risen gradually over the last 20 years, with the growing Hispanic population responsible for most of the increase.

No one here is claiming to have entirely solved the district’s problems—urban crime and poverty are still a reality in Long Beach—or to have perfected the schools. But there has been steady progress since the mid ’90s when the city was plagued by high dropout rates and known as a home base for gangs.

Leaders here say their success since then is due to the unusual level of cooperation between the three systems, a collaboration that expanded in 2014 when the City of Long Beach joined the group. “You can’t do it by yourself,” said the Long Beach schools’ superintendent Christopher Steinhauser, whose district offers classes from preschool through high school. “It doesn’t mean we have unlimited resources and everyone’s going to get everything we want, but we’re going to prioritize and go for that north star, which in our case is student achievement.”

Still, even with all that cooperation, making improvements that have a measurable effect on students’ life prospects is a slow process.

“We’re dealing with human change,” said Jane Close Conoley, the president of Long Beach State. Changing human behavior does not happen overnight, she said, but with steady, focused attention, shifts can be made. “We’ve been in it for a long time and we’re in it for the long run.”

While the structured collaboration with the higher-education community formally dates to 2008 when the group organized the Long Beach College Promise, representatives of all three entities say the informal, open-door nature of their relationships started earlier. By Steinhauser’s count, 2016 will be the 24th straight year of focused improvements in his school district, many of which can be traced to the ongoing cooperation with the local community college and state university.

Long Beach students performed nearly as well as the state average on the new Common Core-aligned assessment given in spring 2015, despite having a higher percentage of economically disadvantaged students than the state as a whole. Thirty-six percent of Long Beach students met or exceeded the third-grade reading standard, for example, compared to 38 percent statewide. And students from economically disadvantaged homes here performed slightly better than their economically disadvantaged peers statewide at nearly every tested grade level. There’s no past year comparison for the test students took last spring, but Long Beach students’ scores on the old state test had been improving steadily for more than a decade.

The district’s graduation rate has hovered around 80 percent since 2010, when the state last adjusted the way it calculates these numbers. The state graduation rate just caught up. Seventy-five percent of high-school graduates here attend college within one year and 42 percent of them, on par with the state average, graduated in 2014 having met the course requirements for admission to the University of California or California State University. Preliminary numbers show that 49 percent of the Long Beach Unified class of 2015 nailed those requirements, according to Chris Eftychiou, the district’s spokesperson.

Long Beach Unified graduates who attend Long Beach City College graduate from that school at higher rates than their college classmates. And if and when they transfer to Long Beach State, they graduate at higher rates than other transfer students.

“It does really become one education system instead of three,” said Terri Carbaugh, a spokesperson for Long Beach State.

It felt that way for Samantha Reynolds, a junior majoring in art at Long Beach State. She was in eighth grade during one of the first years of the formal College Promise initiative. The Promise, as it’s known locally, offers a free year of community college to any Long Beach high-school grad and guaranteed admission to Long Beach State to any high-school or community-college grad who qualifies. The elementary-school tours are included under the Promise banner and so is an actual “promise.” Middle-school students and their parents are asked to sign a pledge to do things like show up to school daily, do their homework, and ask for help from teachers in subjects they find challenging. In exchange for their efforts, Long Beach promises guaranteed college access regardless of family income.

Reynolds remembers the middle-school pledge in less lofty terms. “My history teacher said that if you get good grades, you’ll get into CSU, Long Beach,” Reynolds, 21, said this fall. “I just signed it because they told us to.” But she said it did make a difference to know that if she worked hard and got good grades, she’d get into college. “It was nice to have that there as a guarantee,” Reynolds said, especially since she didn’t feel her parents were pushing her toward earning a bachelor’s degree.

For Robert Fierro, a senior at Millikan High School, Reynolds’s alma mater, the Promise is nice, but he’s hoping it proves unnecessary. Fierro, 18, the son of Mexican immigrants who has “always planned on college,” was able to describe exactly what he had agreed to, and what he could get in return, for signing that middle-school pledge.

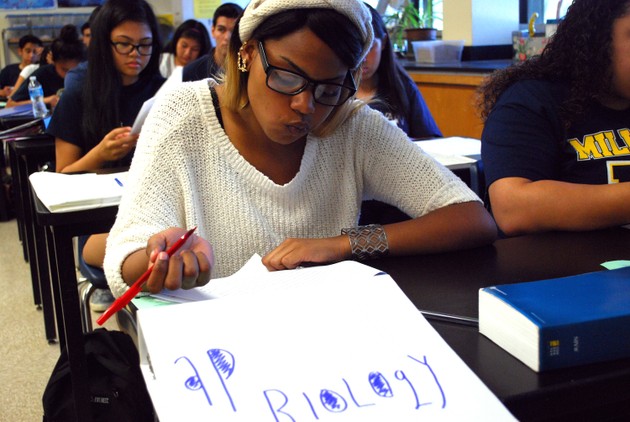

But neither a free year at Long Beach City College, nor guaranteed admission at Long Beach State, has pulled Fierro away from his loftier goal of studying at a University of California school—long considered the best of what the state’s public university system has to offer. Fierro is aiming to major in physiology at the University of California, Irvine, and then go on to medical school. At the end of January, Fierro had been accepted to three schools and was still waiting to hear from UC Irvine and Long Beach State, neither of which has announced freshman admission decisions yet. Meanwhile, he’s taking AP Biology this year in order to test out of the requirement next year. “[I]t reduces what I have to pay,” Fierro said of earning AP credits.

The fact that Fierro is in AP Biology is another element of the city’s focus on student achievement. The district now encourages students to sign up for AP classes even if they aren’t at the top of the class or focused on high-flying careers like law and medicine. And to make sure no one is dissuaded by the cost of taking a College Board-administered AP exam, usually $92 each, Long Beach now subsidizes the cost so that students owe only $5 per test. (The Board offers a reduction, to $30 per exam, for children from low-income families, but families must complete a detailed application to qualify.) In part because of the lower fee, Long Beach has seen an increase in AP-exam completion of more than 41 percent in the last two years. Collectively, students took more than 10,000 exams in 2015.

Changes like opening up AP classes to more students or accepting Long Beach grads with lower qualifying scores than other applicants at Long Beach State haven’t been conflict free. Karen Lima, Fierro’s AP biology teacher and a Long Beach native, said some people worried that students would not be prepared for the advanced coursework or that there would not be enough qualified teachers. But she loves the changes. “Any kid who’s willing to put in the work, is going to get something out of it,” Lima said. “I’ve heard some teachers say, ‘we’re getting more kids involved; that’s going to hurt my pass rate.’ Actually, I’ve seen an increase in pass rates since we’ve broadened access.”

More kids look great on their college transcripts now, she said. And her classes have become more interesting as Millikan High expanded the program from one section of AP Biology six years ago to three sections serving nearly 90 students today. Traditional AP students are “sometimes so by-the-book that they don’t think outside the box,” she said. “Having a broader mix makes the interactions in the classroom a lot more productive because everybody’s surprised all the time.”

About half of Millikan’s sophomores, juniors, and seniors enroll in AP classes and the enrollment now tracks closely with school-wide demographics. For example, 9 percent of Millikan students are African American and 8 percent of the school’s AP students are African American. Nationally, white and Asian students are well represented, or overrepresented in AP classes. And while the gap has been closing for minority students, especially for Hispanic students, African Americans are still underrepresented in most schools’ AP programs.

Lima has taught in Long Beach for 26 years. Teacher longevity is remarkably common in the city. Long Beach boasts a 92-percent retention rate for first-year teachers, Eftychiou, the district spokesperson, said. That’s high for an urban district. Plus, many teachers spend their entire careers here. Long Beach teachers average 16 years of experience, compared to 14 years statewide. That too is part of the design: Long Beach State trains 70 percent of the city’s new teachers, all of whom do their student teaching in Long Beach classrooms. So teachers here know what they’re signing up for when they get their first classroom.

Other California districts, like Richmond and Oakland, have been following Long Beach’s model and setting up similar collaborations. In Fresno, for example, the local school district, the local state university, the city’s early years commission, and a handful of other important players, including the local housing authority, have been meeting regularly since mid-2012 to discuss ways they can share resources. The housing authority has hosted programs like parent-toddler reading and art classes at its facilities. It’s also working to improve Internet connectivity at public-housing sites so that older children can have regular access to online resources.

The great thing about working together, said Preston Prince, the CEO of the Fresno Housing Authority, is that different community groups now focus on how they can help each other achieve their many overlapping goals. “We are in competition for resources,” Prince said. “But what we’re doing is talking to each other about who is the best partner to be the lead and how can other partners be part of the process. I don’t’ think that happened before; before we would just compete.”

Now, Prince said, they still compete, but not with each other. “We want Fresno to be shining more than any other community,” Prince said. “I want this article to be about Fresno.”

Back in Long Beach, at Signal Hill Elementary School, the third-grade teacher Marlene Hamdorf is in her 22nd year as a Long Beach Unified teacher. She credits her long tenure to training at Long Beach State, the mentorship of older teachers at her school, her colleagues’ willingness to share supplies without a second thought, and the knowledge that she can talk to her principal about any issue she’s having without risk of judgment. “It’s a district-wide value,” Hamdorf said. “Sharing everything, not hiding, even our weaknesses.”

That sensibility has filtered down to her students, like Zehnyah Croffie, 9. “I love it because [Hamdorf] helps us when we have a mistake,” Zehnyah said. “She says we’re all her children.”

Lima described the same culture at Millikan High, saying she couldn’t walk into school carrying a stack of supplies without at least three students offering to help her with the load.

College students in Long Beach also said they felt like someone had their back. Martinez-Munoz, the tour guide from Long Beach City College who is now a junior at UCLA, said she felt “important” and “not alone” as a member of City College’s Promise Pathways program, which is meant to help students navigate community college en route to a four-year university.

Those further from the day-to-day work of educating and being educated use terms like “symbiosis” and “flatness” to describe what is happening in the district.

Each Long Beach innovation—from college tours to homework pledges to free tuition to guaranteed admission—is designed to help students growing up in poverty. No one program can solve all the problems these students face, and leaders in Long Beach are the first to admit more needs to be done. And yet, leaders say, none of these programs would have been possible if organizations that usually compete with each other hadn’t decided to ban together instead.

Marquita Grenot-Scheyer, the dean of the College of Education at Long Beach State, remembers how it used to be. People at each organization were always pointing fingers, she said. “You’re not preparing kids,” Grenot-Scheyer said college officials would tell the school district. Then the K-12 district officials would come back with: “You’re not sending teachers who can do it right.” Now, she said, everyone comes to the table trusting that everyone else wants the best for their shared students.

Grenot-Scheyer made these comments while explaining yet another local innovation, called UTEACH, an urban teaching residency in which student teachers are placed at public-school campuses for a year-long program of working in real classrooms every day and taking classes with professors who have watched them teach. Without the cooperation of Long Beach Unified, the urban residency would never have gotten off the ground, she said.

Asked to pinpoint what made these partnerships work so well, she emphasized that what’s happening in Long Beach isn’t just something that’s been written down on paper or summarized in a press release. Everything is built on functional relationships between the people behind each organization, she said. There are few formal structures or protocols required to start a conversation or launch an initiative. Advice, assistance, and new ideas flow freely.

“I have the superintendent’s cellphone and he has mine,” Grenot-Scheyer said, by way of explanation. “And that’s remarkable.”

This post appears courtesy of The Hechinger Report.