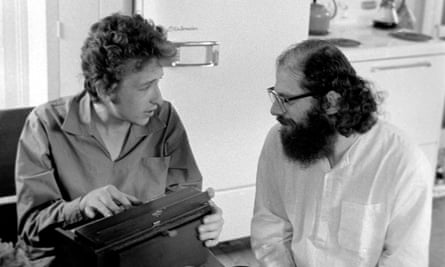

A jam session between Allen Ginsberg and Bob Dylan in the East Village may sound like the apex of Beat Generation romanticism – the Howl poet and Like a Rolling Stone bard draped over one microphone, riffing incendiary ideas and counterculture wordplay. However, the reality of it, in the fall of 1971, was less a bohemian summit and more like a hostage negotiation.

“Bob told me that Allen and Gregory Corso were reading their poetry at NYU, and invited me to come along,” recalls David Amram, 85, a prolific classical/jazz composer and mutual friend. “We went backstage during intermission and Allen told me: ‘My god, I’ve been trying for 10 years to get Dylan to do something musical with me. Will you bring him over to my place tonight, please, please?’ All the years I’d known him, I’d never seen him like that.”

After a dinner of fried clams at Nathan’s, Amram dutifully delivered the semi-retired Dylan to Ginsberg’s apartment near Tompkins Square Park, where Ginsberg opened the door with a guitar in hand. “He handed it to Dylan and said, ‘Key of G, Bob’,” says Amram. “Allen played the one note he could play on the harmonium, and suddenly, he had this whole tape recorder set up on the table. Dylan looked over and yelled, “Turn that ‘expletive’ thing off!”

Despite that tetchy start, Ginsberg did tease out several new folk tunes that evening. Those efforts – topical, surreal, blithely shambolic – can be heard on The Last Word on First Blues, the first box set to chronicle Ginsberg’s most fruitful singer-songwriter years, which spanned that session through the early 1980s. It includes a reissue of Ginsberg’s previously out-of-print 1983 album First Blues, which included a handful of tracks from those Dylan sessions, as well as a disc of previously unreleased tracks culled by Pat Thomas, a historian who specializes in 60s counterculture.

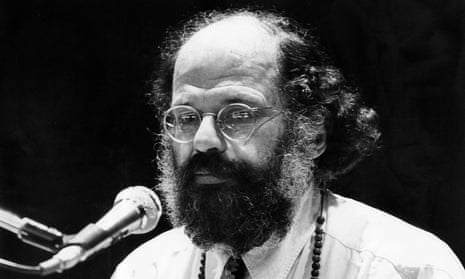

“Ginsberg is obviously an iconic, legendary poet and we all know him as that. Very few people know him as a singer, and even less people like him as a singer,” Thomas admits. He first proposed a box set to the Allen Ginsberg Estate in 2012, 15 years after the poet from died from liver cancer at age 70. “If I’d contacted them and asked to go through Allen’s poems, they’d say, ‘Go away, we have 100 people already doing that.’ I was the only guy who was crazy enough to want to go through the music – and the thing about Allen Ginsberg’s music is, you either dig it or you go running in the opposite direction.”

The Last Word on First Blues is indeed polarizing, true to its creator, whose provocative epic Howl (1955) inspired Dylan and many more counterculture artists of the 60s. Despite Ginsberg’s enduring fame as a poet and the reluctant center of Howl’s ensuing obscenity trial – in which his homosexuality and anti-conformist stances were equally prodded– by the 70s, he already hoped to pivot his career toward music. “Allen, like 90% of America, was enthralled with the image of the rock’n’roll stardom,” says Amram.

First Blues reflects that abundance of ambition; it’s unapologetically ramshackle and hectic with ideas, ricocheting from confrontational folk screeds to droll faux-tropicalia and jaunty ragtime, united loosely in the sort of colorful imagery Ginsberg had already penned in abundance. It opens with the anti-Vietnam war guitar romp Going to San Diego, on which Ginsberg rasps such barbs as “Come to San Diego, show you’re a peaceful man/Old Mr Nixon better bow down to Uncle Sam.” In the background, Dylan, Amram and other downtown friends (including the poet Anne Waldman and musician Happy Traum) smack tambourines, bleat on French horns and harmonize with merry discordance. Dylan’s other appearances are subtle – a yelp here, some guitar strums there – on the delicate piano ditty Vomit Express and a jaunty clarinet bounce vaguely about social equality called Jimmy Berman (Gay Lib Rag).

Elsewhere, on the absurd CIA Dope Calypso, Ginsberg coos an abridged history of American interference in Thailand (“First they stole from the Meo tribes/Up in the hills, they started taking bribes”). The drawling ballad You Are My Dildo, with his falsetto yelps and frequent tumbles into an incomprehensible accent (English? Australian? Ketamine?) could pass for a spectacularly obscene Dr Demento outtake. As a musician, Ginsberg is of modest range; his overall tonal flatness nods most overtly to Dylan and the wily humor also has shades of Phil Ochs, while the unpolished musicianship is pure downtown folk bravado.

Steven Taylor, Ginsberg’s steady guitarist from 1976 to 1992, says the crooning Ginsberg was not without his skeptics.

“I remember one time Marianne Faithfull, who was a good friend, said, ‘Oh, don’t sing, Allen.’ I think there was general feeling he was no good at it,” says Taylor. “But actually, he really did have a talent for music. He had a big vocal apparatus, he could harmonize, he could carry a tune. And he had a funny ear.” He toured with Ginsberg in the 1970s and 1980s, when the writer supplemented his ebbing poetry income with regular treks throughout America and Europe. Often, Ginsberg brought along his partner, the poet Peter Orlovsky, and took the opportunity to wedge songs from First Blues into his literary recitations.

“We would always begin with a song or two, then he would read some poems, then we’d finish with music. It got very colorful at times – Peter would shave his corns while we were performing, clip his toenails,” recalls Taylor. “In Oxford, a local poet denounced our so-called circus act, even went on the evening news to complain. But Allen didn’t care; he had a great sense of humor.”

The bonus disc of previously unheard material in The Last Word on First Blues – which Thomas plucked from 2500 tapes in the Ginsberg archives at Stanford University – is significantly more avant-garde than the frayed folk of First Blues. A spectral minimalism dominates these demos and outtakes, most notably on September on Jessore Road, a 14-minute drone dirge. That track’s baleful cello comes courtesy of another vaunted Ginsberg collaborator, Arthur Russell, who sat in sessions occasionally as a musical arranger.

“It’s a weird curiosity that Arthur’s even on this, but they had a strong relationship,” says Thomas. “Arthur wanted Allen’s music to be more far-out, more freaky, and Allen wanted to keep it in a more conventional folk-blues thing.” (Ginsberg’s occasional mentorship toward Russell wasn’t an isolated example; he also co-wrote a song with The Clash, Ghetto Defendant, replete with a cameo as the voice of God.)

Those who knew Ginsberg best point to the box set as evidence of Ginsberg’s agile mind, even later in his career, and say he had still more to share before his death.

“Allen was still connected in the 90s – he was really into Beck and Nirvana. He’d say, ‘These kids nowadays, they really get it,’” says Peter Hale, 48, manager of the Allen Ginsberg Estate. “There were even talks of doing a Ginsberg Unplugged session on MTV, right before he got the diagnosis that he was terminally ill. Had he lived longer, he definitely would have focused more on music. Who knows what he could have done?”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion