What Is Pinterest? A Database of Intentions

Evan Sharp, one of the co-founders of Pinterest, delves into what the wildly popular image-collecting site is really about, and what it's likely to do in the future.

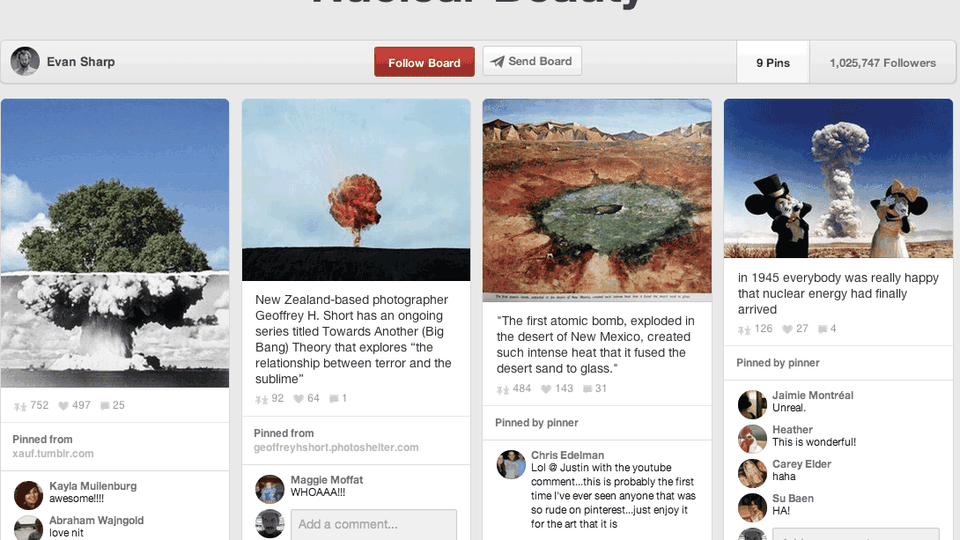

In 2012, Pinterest broke out to become a wildly popular site and app for collecting media across the Internet. People pin photos into collections called boards, which serve as big catalogs of objects. Pinterest, in effect, decomposes web pages into the objects that are embedded in them.

For users, it's a way to think about and plan the future, or to show off one's taste for free. And that's where most people stop thinking about Pinterest. It seems like a shopping site minus the exchange of money part.

But it's on the backend where things really get interesting. Think about what Pinterest is collecting: it's a database of intentions, as I put it for an essay on Fresh Air this week.*

As part of my reporting, I spoke with Pinterest co-founder Evan Sharp about how he thinks about the site. My contention is that Pinterest is one of the four ways that people find things on the Internet. The default, of course, is Googling (or—fine, Microsoft—Binging). For real-time searches, there is Twitter. For people or entities, there's Facebook. But if what you want to find are things, objects, then Pinterest is the way to go.

And they are just getting started. They've got 30 billion pins now, half of them in the last six months. They've got 750 million boards. A full 75 percent of their traffic comes from mobile devices, and according to researchers, they're the top traffic source to retailers' websites and an important secondary source after Facebook for some media sites, like Buzzfeed.

In this wide-ranging interview, Evan Sharp talks here about what Pinterest is now, what it could become, the potential the company has to make money, and how Pinterest competes (or doesn't) with Google and his old company Facebook.

How do you think about what Pinterest is? How do you define it now?

Today, I define it as a place where people can go to get ideas for any project or interest in their life. And as you encounter great ideas and discover new things that you didn’t even know were out there, you can pin them and make them part of your life through our system of boards.

Best of all, as you’re creating a board on Pinterest, other people can get inspiration from your ideas, so there’s this cycle where what you’re creating for yourself also helps other people make their lives.

I think of it as a kind of utility. People use it to save and organize things for later. And then it turns out that integral to saving things is discovering new things.

When I was planning my wedding a few years ago, we wanted to track the things we wanted to put in the wedding. And at the time—it’s kind of like thinking back to Plurk and Twitter—there were all these other services that claimed to let you do what Pinterest does. But you were the only service that actually worked to let us save images from across the web. Think back to that time, just getting the utility working. What did you think Pinterest was then?

I didn’t have grand plans. I don’t think Ben did either in the beginning. It was just the tool I used in my job. I was in school for architecture and when you’re in school for a creative discipline, so much of what you produce comes out of inspiration from other people. The more you’re exposed to architecturally, the better you can develop your own language out of that history of architectural thought. So I had thousands of images that I had saved in folders on my computer. But they were all named like databasestrings.jpg and I had no idea what any of them were. So Pinterest was a way for me to create a link: let’s bookmark an image so that when I go look at it later, I go to where it came from. This is this architect’s building. This is what it is. And collections are a natural way of organizing that sort of inspiration.

So for me, it was very much a professional tool in my industry. For Ben, it was slightly different. Ben used it in ways that you see the broader cross-section of people using it. He used it for recipe ideas, products he was in love with, planning travel. He had a kid. He got married. He did all those things on Pinterest.

Every startup person I know, it’s like their startup was revealed to them long after they started working on it. So when did you know that you had something bigger than a bookmarking site?

You build something and it’s like, what can I build on top of that and what can I build on top of that and what can I build on top of that. Great companies, I think, are the ones that see what they’ve built and can build on top of it and iterate their product.

I don’t remember exactly when we were like “Holy crap! Pins aren’t just images. They are representations of things and we can make them rich and we can make them canonical and link back to the best source and we can attribute this properly to the creator.” (Which is a huge problem that I’m personally interested in.)

I would say we saw that pretty early on, but we’re still pretty early on in executing against that the vision of making Pinterest the largest inventory of the world’s objects.

What’s cool is that because every object was put there by a person. It’s not the largest inventory in the way that maybe a nerd like me would get excited about. But everything that’s on there, at least one human found interesting, so there is a very good chance that at least one other human is going to find that interesting. So, it’s a good set of objects. It’s the world’s largest set of objects that people care about.

One thing I’ve always loved about the Pinterest interface is that when you hit the button to pin something, it breaks the page down into its parts. How much do you think the design of the interface has defined what Pinterest does?

My background industry is design—I code a lot, too—but there’s been this narrative of design in technology becoming more prominent. What the UI enables on Pinterest is this human activity that ends up creating a great database. And it’s that knitting of front-end and back-end abilities that will power our products. We’re not going to be exclusively the best engineering company—though we have some the best engineers—and we’re not going to be the world’s prettiest, best designed company. What’s interesting is how those things interact, over and over, and back and forth. That’s where the magic comes out. That’s where the best new products are coming out on the Internet.

I wanna talk more about the UI. Certain UIs give you a new vocabulary for what you’re looking at. I had never thought about a webpage as a suite of objects hanging on a text skeleton. And the decomposition that your UI does gave me that new vocabulary. Even the way that I’d talk about or gesture to the screen: “Oh, put that thing on the board.” You wouldn’t talk about a link like that.

You know why that is? It’s the way the Internet was architected. HTML is the architecture of the web and it is about the presentation of text. It’s Hyper Text Markup Langauge. And if you’re Google and you’re trying to index that world of information, you’re really great at text because that’s what the code on the Internet does. It marks up text. But if you want to get at objects or the things on web pages, we think you need humans to go in and do that for you. So we think of Pinterest some days as this crazy human indexing machine. Where millions and millions of people are hand indexing billions of objects—30 billion objects—in a way that’s personally meaningful to them.

And even if you had some weird alternate universe markup language, you still wouldn’t get that human valence into the objects. You wouldn’t know what was interesting to humans

Discovery, which is different from search, is a very human process. We’re not building a machine that answers questions, although that’s great. We’re helping you discover the things you like. And part of that is you literally going through the process of discovering them. Yes this, not this, yes this, not this. This idea that you can build a machine that gives you the perfect possibility every time? It makes no sense because you wouldn’t know it was perfect until you saw the other possibilities.

Talk to me about Guided Search, which you all launched for mobile device a few months back.

Guided Search just says, when you search, what are the other things that people add to this search to help you understand the other possibilities. I only point this out, not to market it, but to highlight that the way we think of search is fundamentally different. It’s not just here is my query; it’s a process, a journey. You’re having a kid. You’re getting married. I don’t know what to do, I’ve never had a kid. Type in parenting, and you start to learn, what’s the language of this? On search engines, in general, the relationship to language is very different. You start with the words and you say I want to find these words. When you’re discovering something, we’re helping you figure out the language. If you are interested in discovering something new, you might not know what to type in. Here, the language is the end state.

It feels like you guys have been relying on human-to-human discovery, but you’re starting to roll out more heavy-lifting technical stuff. But people don’t seem to think of Pinterest as deploying a ton of compute power on various problems .

I like that they don’t think of it that way. But this is a technology company. It just is. We have a fucking great engineering team. We’ve solved all sorts of discovery problems that people hadn’t even thought about, all kinds of information database problems that have never been thought about.

And you are working with an impossible to replicate dataset that no one else has, these 30 billion pins. The machine learning aspects of this strike me as fascinating.

Definitely. If you pin something to a board, the name of that board is a string and that string by definition describes it. Someone else pins the same thing to another board. And on and on. One board says shirts, one says ikat, one says gifts for my wife, one says red things. And most pins are on thousands and thousands of boards. So there are thousands of human-generated strings that describe each of these objects. These are descriptions that are very meaningful to the people who created them. It’s not someone trying to make a machine smarter. And we think it will make a machine smarter because it will solve a human problem .

So the question is how do you take thousands of strings and make sense of them?

The question is what problem are you using them to solve. And it’s not just the words. There are also all the images and media that are associated on that board with that pin. Pinterest is very much part of this transition to a visual world. People think of databases as language based, which they are, but database entries aren’t just text entries. They can be anything.

I was reading this book about photography. And it was talking about how over the last 100 years, photos and video became the medium through which we encounter alternate lifestyle possibilities. Magazines, TV. Pinterest is just an acceleration of that effect.

My only point here is that when people think of search they think of words, but there is all sorts of cool computer science you can build with just media, just the images, or just the user graph. And the combination of all that is going to be very interesting. The words are just one signal. They’re super important and we’ve got better words than anybody, but there is all kinds of stuff people don’t even think about because their tools are constrained by language.

This gets to an interesting point: You guys are at an oblique angle to every competitor. There is no one taking on Pinterest head on.

People tried for years to clone us. Straight up stole my code. Stole the brand. They didn’t succeed yet. I think they won’t succeed, but there are services that touch us on the edges. Discovery is not something that we do exclusively. I don’t think it’s a problem any other company is focused on as much as we are. It is our company.

It seems to me that the most competitive overlap in the near future is Google. You think about the tools we have to find stuff. You might use Twitter for real-time search, search on Facebook for a person or institution, search on Google. And maybe search on Pinterest. That’s kind of it. And they are really different kinds of information.

Search for most people is web navigation. It stitches together the human information on web pages. It’s also a tool for answering questions. We weave them together, but you could decompose those in an interesting way if you were interested in solving search as a problem.

It feels like you’re just moving into these spaces. You’ve got all these images, what kind computer vision stuff can you do?

You’ll see. We acquired a company recently that specializes in that. It’s a very small company but there are all sorts of ways of pulling information out of images and using text to understand what you have. There are all sorts of ways of using that information. For us, it’s all in service of discovery.

We’d never beat Google at being Google. That company, their brand is scaling computer science. And I love Google for that reason.

An interesting thing about Google’s approach to search is that the way it wants to provide answers now doesn’t help me think better. At least not since they launched Google Instant which was pretty good for that.

That was our head of discovery.

I feel like it was the last great Google search product because it didn’t just execute the search, it taught me how to search better .

The process is part of the experience.

But it seems like Google is obsessed with getting rid of the process of search.

You should go watch the keynote of the head of Google search at the last [Google conference] I/O. His talk was about the vision for Google Search, which is exactly that: they are building that computer from Star Trek where you ask it a question and it answers. Which is amazing. It’s an amazing goal. But you’re right, there’s a whole world of searching and discovering that’s about the process itself. And that’s an interface driven experience.

Let’s talk about another way Pinterest is different: the female, non-coastal nature of the user base, or at least the initial heavy user base.

There is a seed of wisdom in that. The demographics it grew within. The geographies it grew within. The fact that it is ending on the coasts and didn’t start on the coasts. I can’t think of any other services that have grown this way.

How contingent do you think that was? One test for how contingent it was would be to say, is this what happened in the UK? What happened in Spain? Did you find in Spain, it was Barcelona-first, then the hinterlands?

I don’t think we can talk about that yet.

Pinterest had such obvious business possibilities from the get go, I’ve always wondered how much it influenced the culture of the company that the commercial potential was so obvious?

We’re lucky. We can make money without creating that second head that makes you say, “What is that doing there?” For me, personally, Ben and I want to build a big company and make a lot of money, so we can do cool stuff. But we’re not intrinsically motivated by money. We would have sold this thing if that’s what we were after personally. And for me, what’s been really important, there’s so much potential, and I don’t want to sound megalomaniacal or stupid, but it could be really good for the world in a way.

I know that sounds preposterous, but I’ve always worried that that people and marketers would be so eager to get their hands on it that it could be bad for the core. The things people do on Pinterest are so precious: this is what I want, this is what I think I want. They’re not ever sure, they’re feeling their way through. It’s a very weird emotional state. It’s this very beautiful thing to me. And if you start loading it with commercial pressure, it could really ruin the core of the experience. It doesn’t mean there isn’t a place for ads and a way for us to make money to sustain the business and the site, but that’s something that’s always been in my head. It’s one of the reasons why we invest in research and having a more active brand team. We have a community team that’s super active. All those things are just ways of understanding what the core experience feels like to people and making sure that we’re not messing it up.

What I mean is that some businesses that start from a premise of data-gathering have to make an argument that that data will be worth a ton once they can figure out how to monetize it, even if it’s kind of crazy. You run into people who are like, “We’re gonna fly drones across the entire country … to make marketing more effective.” And I’m like, “Wait, I don’t even understand what’s going on anymore?”

Dude, that’s the thing. I didn’t set out to build a business brand. I set out to build a product. We’re very lucky. And the good thing for us is that anyone who builds this stuff—monetization tech—they want to work here. Because the potential is so obvious to them. So we get to choose the people who are the best culture fits and the most brilliant. That’s a luxury we have that we do appreciate.

How would you compare yourself to Facebook?

I used to work at Facebook. And fundamentally, Pinterest is about inspiration. And inspiration is a word that doesn’t resonate with people until they use Pinterest and get what that means, but that’s fundamentally about connecting to other people. Other people end up being people’s source of inspiration, which also happens on Facebook. So, we’re like Google in the data model way, but we’re like Facebook in the more experiential way. The way you discover is a combination of the two.

So, how do you see yourself opening up the social potential of Pinterest?

Zuck describes Facebook in the press, I might butcher his words, but he’s like people have a psychological need to spend time and know about and learn about the people they care about. It’s built into our brains and its Facebook’s job to remove as much effort as possible from that, so you can fulfill it any time you want to. Pinterest is not about your friends, it’s about yourself. It’s about the things you want in your life, the possibilities. What can my kid’s first birthday party look like? It’s very future-looking in a way that Twitter and Facebook are very right now or backwards looking.

Pinterest is about connecting you with people who manifest one thing you want your life to be like. So, if you are getting into photography, what do you do? You read photography blogs because these guys or girls are really into photography. They love their photos. They’re talking about how to do it. People develop taste through other people, whether that’s celebrities or people they know. And we have the data to understand—in a very non-creepy way, honestly—who are the people on Pinterest that manifest and express the things you look like you’re interested in.

That’s why Pinterest doesn’t just show an image. It’s an image with a person. That was a very deliberate decision. Everything on Pinterest was put there by a human being and—in aggregate—we can figure out who are the human beings who are the enthusiasts in the thing that really interests you. And those are the people who can guide your journey in that interest or project you’re planning.

People are fundamental not just for our data model, but because eventually, we’ll be able to connect you the people who really share your taste and express who you want to be. And that’s something that’s happened for decades in magazines and on blogs and on TV.

Huh. One of the things that I tend to like about Pinterest is that it feels less social. There are so many things where it’s like, jesus, all you want me to do is connect in some abstract sense.

If you look at the startups that are getting really big right now, they are either all friend messaging apps. What’s App, Line, Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat all of them do that. Which is great, there’s a playbook, you get the address book and you go from there. Or they are marketplaces, Uber and Airbnb.

Exactly. Touch my phone and something happens in the world.

Which is great. We’re this weird different thing. We’re not gonna grow the way the messaging apps are gonna grow. We’re not building a marketplace of sellers or creating an inventory of services. So we’re a very weird company right now.

In a lot of corners, it seems like interest in the iPad is declining, but it seems like y’all are big on the iPad.

iPad is my favorite experience by far. It’s one of the perfect iPad apps because it’s a grid. If I can soapbox for 60 seconds again, the grid is like the thing that got us big. The grid, the grid, the grid. Pinterest is about browsing through objects and picking out the ones that are meaningful to you. And what the grid does is facilitate your ability to go through objects in an efficient way. Our job is to put the right objects in front of you to start with. But the iPad is the perfect place for us because that screen is tailor made for sitting there are browsing through things.

Are you the reason there is so much retailer traffic coming through the iPad?

I don’t know. But the second half of my thought—and this comes from my architecture background—if you think about discovery as this experience people have. Discovery is this thing that people do all the time right now in stores, in museums, in physical spaces. So many of our public physical spaces are organized around a collection and they are organized to help you access and browse through that collection to find the things you find meaningful. We’re just a digital version of that experience with a much larger inventory that cuts across different types of things.

But the reason I mention that is that the reason retail feels like an obvious fit for us is that you’re doing on Pinterest what you do in a store, browsing through things and picking out the things you like, saving them for later, and maybe eventually buying them.

But all that goes back to the UI, goes back to the design of the service, goes back to the screen you’re on, goes back to data that we use to power what you’re looking for. That was my soapbox.

* After I published my story, a reader pointed out that John Battelle coined this phrase in 2003 to define a larger set intentions, which is to say, all searches. My usage is much narrower. My apologies for any confusion.