These are the ground rules: You can’t say Earth is your favorite planet. This was the framework my colleagues established in a recent newsroom debate over which of the classical planets is the most awe-inspiring. Picking Earth would be obnoxious. Like saying your spirit animal is a human. Well, fine. I pick Jupiter.

Gargantuan, swirling, violent Jupiter. A planet made from the cloud that formed the moment the sun was born. A gas giant that contains more than twice the material of all the other planets in our solar system combined. Huge enough to house 1,300 Earths, and with a midsection that spans 44,308 miles. (The radius of Earth is 3,961 miles.) Jupiter, where winds blow at several hundred miles an hour constantly—as in, all the time and without letting up. Jupiter, where the average temperature is a frigid 235 degrees below zero, but where it gets hotter than lava at lower and lower cloud layers. Jupiter, which gives off more heat than it gets from the sun. Jupiter, where the raging weather includes a mammoth anti-hurricane that has been churning for something like 400 years.

That epic storm is what you see when you notice the planet’s famed Great Red Spot—a massive high-pressure system, equivalent in size to three of our home planet. But it’s not always red. “It’s kind of orange and it changes color,” said Amy Simon, a planetary scientist at NASA. This is just one of Jupiter’s mysteries. From far away, the planet looks vaguely beige. But its clouds are a kaleidoscope of warm colors—alternately red, orange, pink, and tan, with some blue. That may be the effect of sunlight breaking down chemicals like ammonia, but scientists aren’t sure. “We still don't know what makes the clouds the colors they are,” Simon said. “Another thing we don’t know is: Why the storms last so long.”

The planet’s intense weather seems to play a role in its ever-changing color scheme. When scientists observed fireballs raining down on Jupiter in 2010, they looked like little dots from afar. In reality, they were meteors the size of military tanks that released 1015 Joules of energy on impact. “For comparison,” NASA wrote at the time. “That’s five to ten times less energy than the Tunguska event of 1908, when a meteoroid exploded in Earth’s atmosphere and leveled millions of trees in a remote area of Russia.” Jupiter has seen worse. In 1994, it was hit with a torrent of mountain-sized pieces from a dying comet, a bombardment that “ignited flashes on Jupiter... that outshone the giant planet itself,” The New York Times reported.

One of the fireballs that spun out from the impact was as large as Earth. (Incidentally, Jupiter has protected Earth from many, many comet impacts. Some scientists believe that Earth owes its habitability to Jupiter for this reason.) The collision sparked unimaginable storm systems. “We can look at Jupiter like a weather laboratory,” Simon said. The thunderstorms on Jupiter are epic, more intense than “the most crazy weather you can imagine here on Earth.” Scientists know about Jupiter’s electrical storms because they observed lightning—striking the same walls of clouds at the same time, over and over—when the Voyager spacecraft flew by in 1979. Only lightning strikes on Jupiter are 1,000 times stronger than the ones that flicker across the Earth. Jupiter is as extreme as it is tremendous. It wouldn’t be a very nice place to visit,” Simon said.)

Did you know about Jupiter’s rings? It has four of them. A bright, thin ring sandwiched between a thick halo of particles and two gossamer rings that are made from moondust.

Then there’s the dizzying rotational speed of the planet; a Jupiter day lasts a mere 10 hours. Oh, and have I mentioned the vast ocean of liquid metallic hydrogen? The lightest element on Earth, one that would make a balloon float skyward in our atmosphere, churns in liquid form on Jupiter. There’s no way to know what this looks like. “Not only are we talking about something nobody’s seen, but we’re talking about something that only exists at pressures that are 2 million times the pressure we’re used to on Earth—and down underneath the atmosphere, so it’s dark,” said Steve Levin, a project scientist for the Juno mission to Jupiter. “In my head, I picture it looking vaguely like liquid mercury.”

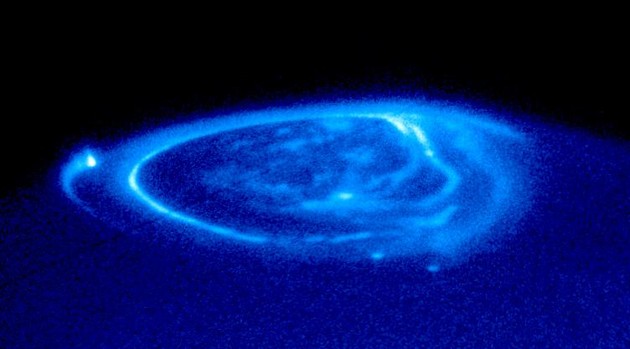

Whatever it looks like, a dark, roiling sea of this stuff conducts electricity, which is what generates Jupiter’s mega magnetic field. That force is strong enough that it’s been used as a kind of slingshot to boost passing spacecrafts. It is the most powerful magnetosphere of any planet in the solar system and it feeds into Jupiter’s vast radiation belts, bands that are made of high-energy particles and electrons moving at close to the speed of light. Jupiter’s magnetism, in turn, feeds into exquisite neon auroras at either of the planet’s poles—stunning electric blue, speckled with glowing dots and swirls—more dazzling than even their most extraordinary counterparts on Earth.

“If you look at the North and South poles of Jupiter, it’s got northern and southern lights—only enormously bigger,” Levin said. “And they have this structure in them, in the aurora, it’s like this lopsided ring and then bright spots [beneath] where the moons are.”

Jupiter’s moons, of course, have their own appeal. For one thing, there are hundreds of them. Which means phenomena like triple eclipses occur on Jupiter. Galileo spotted the planet’s four largest moons—Europa, Ganymede, Io, and Callisto—four centuries ago. He thought they were stars at first. The realization that they were moons orbiting Jupiter was shocking, and the implications cannot be overstated; Earth, it turned out, was not the center of the universe.

Which means Jupiter, a giant ball of gas that’s half-a-billion miles away from Earth, was key to humans reorienting ourselves in the wider universe. More recently, the Galileo probe that NASA sent to Jupiter collected data that helped cosmologists’ predictions about the Big Bang. Later this year, the Juno mission will capture new information about Jupiter using radio waves—a method that will encompass more of the planet than is possible by using a probe, which cannot descend very far into the Jovian atmosphere before being crushed by the pressure. For a world we’ve barely laid eyes on, what Jupiter has taught us about the universe is even more astonishing than it is consequential. “When you look at Jupiter, what you’re looking at is the enormous clouds,” Levin said. “You look at it and you see all this amazing stuff that looks like an oil painting, with belts and zones and a hurricane that’s been around for hundreds of years. To me, what’s most amazing is the fact that we’re looking at the tops of clouds, this tiny layer. It’s like looking at the outside of an orange.”

“Every time we look at it it’s different,” Simon said. “The weather, these clouds, it keeps changing.” And we will keep looking. The Juno spacecraft that launched four years ago is set to reach Jupiter in 2016. There, it will transmit photos and data that could fundamentally change the way we understand the planet—and the formation of the entire solar system.

Ah, Jupiter. Good ole Jupe. The best planet, that cosmic bruiser, big enough to boggle the mind and bright enough to cast shadows on Earth. Of course, from Earth, Jupiter appears as a lovely pinprick on the night sky, a faint pink jewel that seems far gentler than we know it to be.